A few years before his death, Marguerite Lovewell Grigg’s boy, Harry Kingsley Grigg, Jr., got to see the movie version of his most famous case. It wasn’t really his case per se, and probably wasn’t even the most interesting one his detective agency had worked on, but it was a caper that made headlines forty years earlier, and he had played a small supporting role in it.

The caper was the production of a fake autobiography of Howard Hughes by writer Clifford Irving and a few co-conspirators, and the sale of their fraudulent manuscript to McGraw-Hill Publishing for over a million dollars. Irving was betting that the reclusive Hughes would not come out of hiding to unmask their scheme. He made the wrong bet.

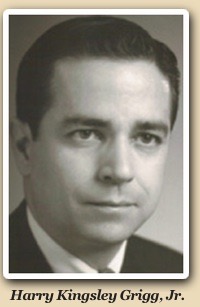

As the hoax quickly unraveled early in 1972, Clifford Irving needed someone to fly to Ibiza and collect $50,000 in Swiss francs that he had stashed behind a rock near his Mediterranean farmhouse. He immediately thought of Harry Grigg “with his merry brown eyes and modified Groucho Marx mustache.” He called Interstate Security, the agency Harry Grigg had joined after his stint with military intelligence, rising through the ranks at I.S. to becoming president of the firm. When Irving described the job, Harry jumped at the chance to get out from behind his desk and handle the case personally. After it was done, he called from the airport at Ibiza to tell Irving and his lawyer that he had mowed the lawn, washed the laundry, and gotten the summer clothes. The men were flummoxed. Had Harry suffered heatstroke? No, his associate at Interstate Security hadn’t called to tell them the code words Harry planned to use, or what they meant.

In his confessional book “The Hoax,” written decades after his release from prison, Irving makes Harry Grigg sound just a bit like that other clandestine operative with a mustache whom the world was about to meet, G. Gordon Liddy, who was fond of code words and disguises and the other trappings of spy novels. Apparently, the two men had little else in common. I don’t remember anyone ever referring to G. Gordon Liddy’s “merry brown eyes.”

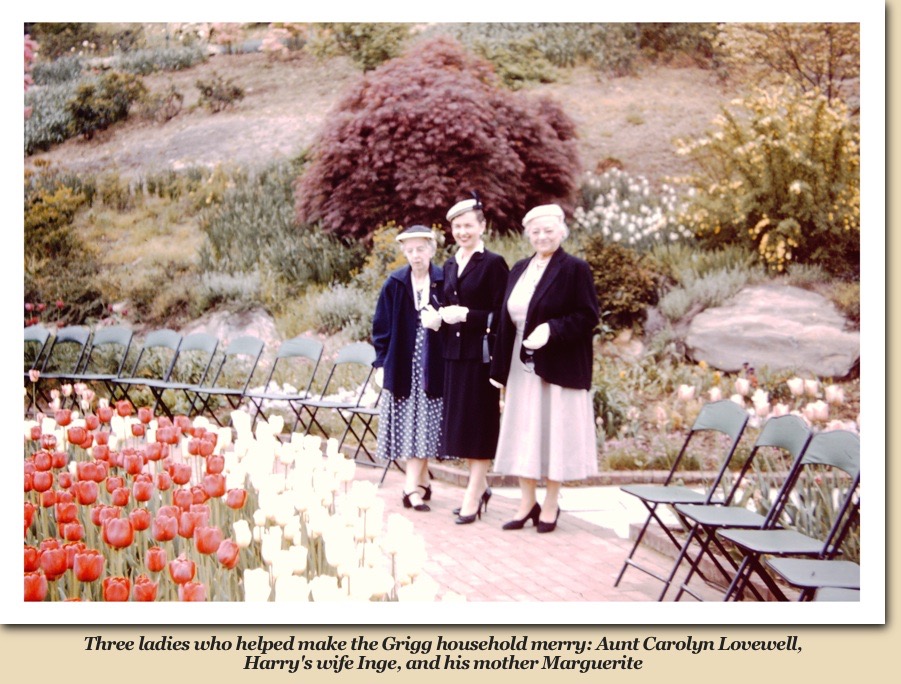

His daughter Kathy Knight remembers Harry as "an awesome man and was so kind and loving to everyone. He was very generous and always donated money to numerous charities. He was the best dad ever and had a very exciting life.” She also fondly remembered her grandma Marguerite’s "huge hugs" and Auntie Carolyn’s “unbelievable cookies.” I know what she means. Maiden aunts fill a niche no one else can. No one except my Aunt Ruth ever read me bedtime stories about carrier pigeons in World War I. Her kitchen (Actually my grandmother’s kitchen, but Ruth’s domain) was a culinary laboratory for hollowing out French puff pastries to be filled with tasty goo and topped with powdered sugar. It’s where I experienced my only ever taffy pull. Oh, yes, she also introduced me to her favorite real-life Western hero, Thomas Lovewell.

But, getting back to Harry Grigg and Clifford Irving - what did Harry think of the movie? The 2007 film, starring Richard Gere and Alfred Molina as partners in crime, is a funny riff on the book, sometimes improvised by the actors. That’s appropriate, considering the fact that Irving went through frantic brainstorming sessions to whip up the fake autobiography, and then had to manufacture elaborate lies on the fly for an audience of McGraw-Hill executives. Harry Grigg's verdict that “it wasn’t very accurate,” may be apropos, but it’s still a good movie.

The book is a fun read as well, although I was hoping for more Harry. He’s only in the few pages Kathy had already shared with me, but I’m enjoying it. I downloaded the ePub version, the second time this week I’ve made that choice, because, while I prefer having a physical volume that I can keep on my nightstand and dog-ear or mark my place with my folded reading glasses, the electronic versions are exhaustively indexed and microscopically searchable. I already owned a used copy of LaVonne J. Perkins’ “D. C. Oakes - Family, Friends, & Foe,” but downloaded one from the iTunes Bookstore a few days ago so I could quickly root out every mention of Oakes’ ill-fated infant daughters, after realizing that the death of one of them is commemorated in the Pikes Peak photo.

D. C. Oakes, you may recall, was such a relentless promoter of the new town of Denver City, that he was remembered as the architect of the Pikes Peak Gold Rush, especially by disappointed gold-seekers who buried him in effigy along the trail during their tired trek home. During some of his own travels between Iowa and Denver, Oakes encountered angry mobs and sham graves that had been marked with epitaphs such as, “Here lies D. C. Oakes, Killed for aiding the Pike’s Peak hoax.” Embittered miners with empty pockets declared that it was no accident that “Oakes” rhymed with “hoax.” So I’ve recently added two books to my electronic bookshelf, both about great American hoaxes, one set in the 19th century, one in the 20th. In both cases a descendant of Captain John Lovewell is caught in the spotlight as he stands innocently near the margins.

I’m by no means finished with Marguerite Lovewell, by the way. Just yesterday I discovered that she was chosen as the featured soprano for the Ellis Club of Los Angeles in their closing concert of the summer season in 1914. The news item is a small one, leaving room for the big news of the day, the upcoming bout wherein “Great White Hope" Jim Jeffries would get his clock cleaned by Jack Johnson. The clipping from the Topeka newspaper made me feel better about my own typographical mishaps. In it, Marguerite’s given name is spelled three different ways - and remember, this was her hometown paper. So if you find yourself stymied in your Internet searches, remember that a little creative misspelling sometimes helps.

I don’t plan on giving up until I have a picture of Marguerite onstage in costume as Meevya the Moon Maiden from the world premiere of the operetta at Fitchburg in 1913. There has to be one, somewhere in the archival libraries of composers Stoddard and Berton, or the Whalom Opera Company. If only Harry Grigg were still around, I could hand him the job. Oh, and if Dave Lovewell happens to read this - that thing we talked about that you wanted - I’ve collected the summer clothes and they’re on their way.