I wasn’t looking for news as I started leafing through pages of the Virginia Evening Bulletin from April 1864. I was more interested in the ads, hoping to learn what sort of entertainments the Comstock District had to offer an ex-soldier, newly-sprung from his long vigil at Fort Churchill, that might entice him to part with a hard-earned 50-cent piece. For the thirsty, there was the usual abundance of saloons. But if Thomas Lovewell wasn’t a teetotaler, neither was he an habitual and determined drinker. He may have hoisted a few rounds in salute to the two brothers he had lost in May of the previous year, but that ritual would have grown old quickly.

After two years and five months of soldiering, Thomas, a haggard scarecrow with ailing lungs, established temporary quarters at Dayton where he would rest up and ease back into civilian life. Dayton was a small mining town where rent was cheap and the oyster bars and music halls of Carson City and Virginia City were a short stagecoach ride away. As he began to get his strength back, he could pocket the stagecoach fare and hike to Virginia City in a couple of hours. What would he do when he got there?

An avid music-lover might have attended a concert by the Germania Singing Society, "the first production in the Territory" of a German comic opera called “The Four Bald Heads.” There was the first annual ball of the Nevada Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 going on at Sutliff’s New Musical Hall, or the Ladies’ Promenade, Concert and Ball at Gold Hill Theatre, featuring a performance by the Virginia and Germania Glee Club at 8 o’clock, followed by dancing at 9:00. None of these strike me as Thomas’s cup of tea.

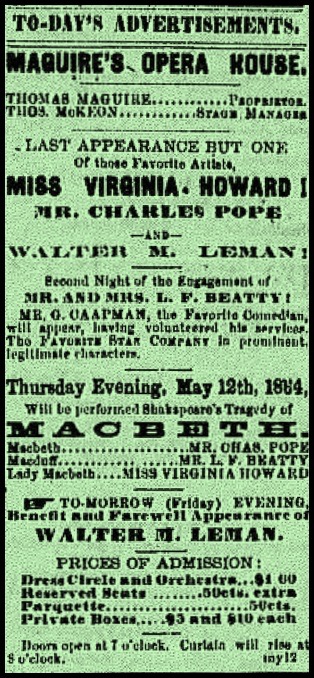

Then, a series of ads caught my eye promoting a theatre troupe which had been installed in Maguire’s Opera House at Virginia City where it would continue to perform a blend of domestic dramas and Shakespeare until summer. A veteran Shakespearean actor named Frank Lawlor, who was said to be on his farewell tour, would star in “Hamlet,” although the ads made it clear that the troupe’s real drawing card was the beautiful young actress playing Ophelia, “Miss Virginia Howard!” Yes, in newspaper advertisements Miss Howard’s name was usually accented with an exclamation point. She played Katherine in “Taming of the Shrew,” Julie, the Cardinal's ward, in Edward Bulwer-Lytton's “Richelieu,” the murderous Thane’s bloodstained lady in “Macbeth,” and the title character in “Aurora Floyd!"

The website Goodreads.com gives a neat summary of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s story of young Aurora Floyd, which had been published as a novel, one with no exclamation point after the title. The punctuation mark would have been added by the newspaper copywriter to indicate that this was not only a recent best-seller, but spicy stuff.

Like Lady Audley, Aurora is a beautiful young woman bigamously married and threatened with exposure by a blackmailer. But in Aurora Floyd, and in many of the novels written in imitation of it, bigamy is little more than a euphemism, a device to enable the heroine, and vicariously the reader, to enjoy the forbidden sweets of adultery without adulterous intentions.

It may have been a case of life imitating art or vice-versa, but Miss Virginia Howard’s life had a little something in common with that of the fictional actress Aurora Floyd, the character who unintentionally enjoyed those “forbidden sweets of adultery." “The History of the American Stage” has less to say about Virginia Howard's talent or career than her complicated domestic situation. Married to Scottish actor P. C. Cunningham when she was only sixteen, she separated from him and then married another actor, Charles Pope, who later had their marriage annulled on the grounds that Virginia's first husband was still living and the pair had never divorced. However, before Virginia Howard and Charles Pope split, the two still had to share the stage in “Aurora Floyd,” a story that may have hit too close to home. The 1863 premiere in San Francisco had to be postponed when Charles Pope fled the theatre just before the curtain was supposed to go up. He returned to the show a few days later and the play finished a successful run in San Francisco before the company took it on the road to Nevada Territory in the spring of 1864.

In 1868, amid reports that “the favorite and well-known actress (formerly Mrs. Charles Pope) had married a professional at Mobile,” the Sacramento Daily Union passed along the news “from what we deem to be the very best authority, that Miss Howard was not married, but that she died of heart disease about three months since.” While she may have broken a few hearts among her admirers by sampling those forbidden sweets one more time, several newspapers, among them the Petroleum Centre Daily Record quickly put the rumor of her untimely death to rest:

Tonight will be produced the 'Octoroon; or, Life in Louisiana,' in which Miss Virginia Howard will appear as Zoe the Octoroon, and Mr. S. K. Chester as Jacob McClosky, with the entire company in the cast. We hope to see a crowded house.

Miss Virginia Howard would live on and could still be found touring the West with an acting company in the 1890’s. Thomas Lovewell's health improved enough to allow him to visit his brother Solomon in Washington Territory, and then head east to begin the second act of his life in Kansas. In 1883, he may have recalled an evening’s entertainment and a beautiful young actress in a starring role when the last of his children, Diantha Desdimona, was born at White Rock. Diantha's middle name could be a memento her father brought home from Virginia City after viewing Shakespeare's play about an ex-soldier who hoped to be remembered as "one that Loved not wisely but too well."