I once accused Roy Alleman of including a recipe in his book “The Bloody Saga of White Rock” chiefly because it was the only scrap of family lore that Gloria Lovewell had left out of her exhaustive compendium “The Lovewell Family.” The recipe Alleman found was a strapping, manly one for curing buffalo hams, a process that doesn’t get much of a workout anymore.

There is an actual Lovewell recipe book, one from the Topeka Lovewells, and it too seems dated, though that’s part of the fun. When I learned that a 1908 edition of Caroline Barnes Lovewell’s book “The Fireless Cooker: How to Make It, How to Use It, What to Cook” was available for online browsing at Openlibrary.org, I decided to have a look. What I found myself leafing through instead was “High Living: Recipes for Southern Climes.” It was another vintage cookbook, one that might have its merits, but it was not the book that resulted from Caroline Lovewell’s collaboration with her husband, Prof. J. T. Lovewell. To get that book I had to pretend to be searching for “High Living,” and when presented with two digital choices, pick the cover that didn’t look like the one I had just seen. Maybe they’ll fix this case of mistaken identity someday. In the meantime, looking for the wrong book can lead you to the right one.

The first part of “The Fireless Cooker" is a translation in layman’s terms of Prof. Lovewell’s paper, “Economy of Heat in Cooking,” which addressed the nasty truth that a large amount of heat is squandered in meal preparation, just as “the potential energy of fuel, when applied to steam-engines is largely dissipated without mechanical or other useful effect.” We heat up our kitchens, allow steam to condense on our windows, and generally smell up the place, all quite unnecessarily, according to the professor. “In most of these operations the essential thing is the maintenance of requisite temperature long enough to secure those chemical changes and that breaking up of starchy or proteid constituents which renders the food palatable and easy to digest.” Whew. Hardly “The Art of French Cooking,” hence the need for his wife’s companion volume to make the idea of scientifically-sound fireless cooking seem tasty.

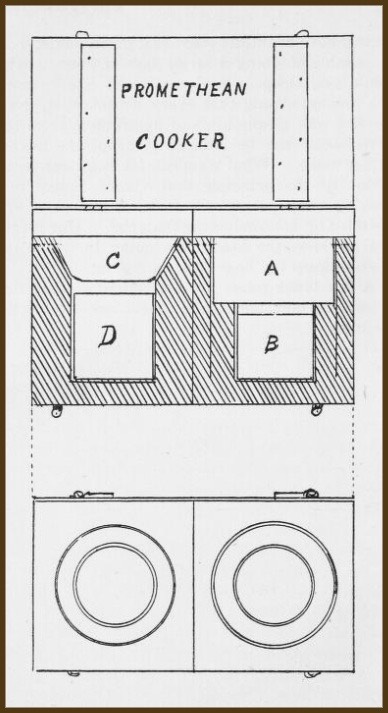

One early chapter is devoted to instructions and blueprints for constructing a home-brew version of a fireless cooker, which the authors dub the “Promethean Cooker.” The essential idea was to make a snugly-insulated box with just enough space for a pair of kettles and their lids, and an insulated top to cover everything. Kettles of food were brought to boil, removed from the stove, placed inside the cooker, and sealed up. Hours later, after the kettles were removed from the box, the simmering contents could be stirred and served. Having no place else to go and nothing better to do, as the professor pointed out, the heat applied that morning, spent all afternoon cooking your supper.

As might be expected from the cooking method used, soups dominate the recipe section: Cinderella Soup, Green Corn Soup, Easau’s Pottage, Hasty Soup, Mock Oyster Soup and many more. Sections on fish or poultry and game are shorter, but include methods of making Fried Chicken, Chicken Fricassee, Jugged Rabbit - the English Way, and special instructions on How to Roast an Old Fowl. The key in the latter case was to steam it in a kettle for forty minutes before making it sweat for twelve hours in the fireless cooker. After its ordeal, stuff as usual and roast for another ninety minutes.

The fireless cooker and Mrs. Lovewell’s cookbook may have arrived twenty or thirty years after they were most needed. Imagine a pioneer wife doing the day’s food preparation all at once, and then tucking the hot dishes away in a corner to simmer undisturbed without having to fire up the woodstove again on a hot summer afternoon.

Not content to make a fireless cooker, the professor and his wife had also tinkered with a fireless steamer which operated under the same principle, and next turned a discarded icebox into a combination stove and oven. His insulated cooking box was also the ideal instrument for making ice cream, the professor contended, one that required less salt, ice and labor than the traditional ice-cream maker. There were no paddles to turn, but paddles contributed nothing to the process anyway, according to Prof. Lovewell.

As Caroline Lovewell wisely observed, "The idea of fireless cooking is still in the process of development, and the most finished cooker of to-day will, no doubt, seem to the future housekeeper as crude and primitive as does the Indian bake oven to us.” Not to mention what the Health Department would make of shoving a chicken in a box lined with asbestos insulation, and keeping it there for twelve hours, or until it was completely delicious.