Taking stock in 1883, four years before the end of his adventurous life, Denver pioneer Daniel Chessman Oakes expressed one paramount regret.

Of the myriad boxes stuffed full of pamphlets that had made him famous and infamous across America a quarter of a century earlier, Oakes had not saved a single copy for himself.

He would be willing, he said, to pay $10 to have one, although the pamphlets had not sold well enough to defray the printing costs - this despite the fact that a quarter of the pages were devoted to ads.

There had been ads for hotels and outfitters at staging points along the Missouri River, and for attorneys who surely would be needed when the reader of the guidebook eventually struck it rich.

Two years before Oakes penned his thoughts, the editor of the Smith County Pioneer had shared a similar story about another pamphlet that was stuffed full of ads, a pamphlet which had met with a similarly tepid reception.

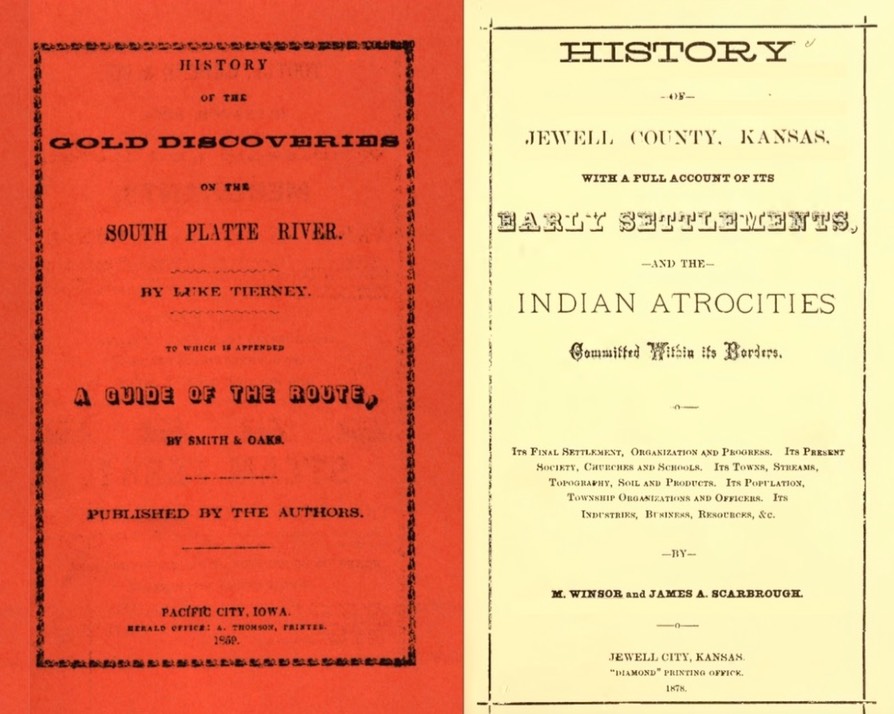

I have before me, as I write, a little pamphlet printed in Jewell county in 1878. The title is, in brief: “A History of Jewell County, Kansas, with a Full Account of its Early Settlement and the Indian Atrocities Committed within its Borders.” It bears on its yellow cover the names of M. Winsor and James A. Scarbrough.

Aside from its value as a true story of a Kansas county, it has a meloncholy (sic) interest to me, for it was my duty to write the last chapter of the story of one of its authors, poor Scarbrough, when the record of his troubled life was finished forever.

The little book, as its surviving author tells me, was a financial failure, and yet it deserved a better fate. In future days the curious collector will doubtless pay more for a single copy, obtained after long and careful search, than was realized by its first publishers.

The editor of the Pioneer had little else to say about James Scarbrough’s “troubled life,” except that “Jim never at heart was dishonest, but his ambition got the better of his judgment.”

The deeds which clouded the reputation of James A. Scarbrough took place in Jewell City (today’s Jewell) in his capacity as the town’s postmaster and freight agent. In the last state election he had made a vigorous and expensive run for the office of Kansas Secretary of State, financing his campaign by embezzling between $1,500 and $2,000 in an era when a typical monthly wage was about $70. After losing his bid for the party’s nomination he disappeared from town, abandoning his wife, their child, and his widowed mother. The existence of a widowed mother was seldom omitted in press accounts.

Major John M. Crowell, special agent of the Post Office Department and United States detective tracked Scarbrough from Wallace, Kansas, headed toward Del Norte, Colorado, where the fugitive apparently planned to disappear into New Mexico Territory.

The story of his capture made thrilling front-page news across Kansas.

Crowell placed his hand upon his shoulder and exclaimed, 'I want you, Jim.’

(Scarbrough) said nervously, 'You needn’t have come after me, John; I was coming back.’

‘When,' Crowell quietly asked.

Scarbrough having recovered his self-possession cooly replied, 'When Gabriel blew his trumpet.’

'Very well,' said the major, 'I blow it now.'

If the capture sounds suspiciously melodramatic, Scarbrough assured fellow reporters that it was all balderdash and that he had already been in custody when Crowell arrived on the scene. His trial was scheduled and then postponed. In the meantime Scarborough's replacement at the Jewell City Post Office turned out to be a either an outright thief or an accomplice who turned his back while his associate pilfered certified mail. Both men had been too inept to cover their tracks and were quickly apprehended.

Scarborough’s own misdeeds began to be referred to in the press as an “irregularity,” while the defendant seemed to go on a rehabilitation tour across the state, lauded by fellow newspapermen wherever he went. There may have been a plea deal or a trial without fanfare, or offstage machinations with just the faint sound of political strings being pulled. Suddenly the formerly demonized fugitive was back in a newspaper office collaborating with Mulford Winsor on a history of the county where James A. Scarborough had first decided to settled down in 1870, at the age of forty.

Over a few eventful years, his life seemed to scream down the tracks like a runaway locomotive. A pioneer storekeeper and founding member of the Buffalo Militia at Jewell City, he married for the first time in ’72. A father, postmaster and railroad agent by ’73, he ran unsuccessfully for public office on illegally “borrowed” money in ‘74, compelling him to make that mad dash into the wilderness to escape the consequences. Brought back to face justice, which seemed to amount to a dizzying series of jobs at various newspapers around the state from Atchison to Hays, he was by ’76 a respected Jewell County journalist in Mankato with a greenhouse to supplement his income.

In the country’s Centennial Year Scarbrough and Winsor began interviewing local pioneers to record the history of the county which would soon become the final resting place for one member of the writing team.

By the spring of 1878 The History of Jewell County was in the hands of the few readers fluent in English and curious enough to buy a copy. By the end of the decade James A. Scarbrough was dead.

Though eulogies would extoll his “patience in the long struggle with disease” Scarbrough complained only of a bad cold in December 1880 when he boarded a train bound for the healing waters of Eureka Springs, Arkansas. Stopping over at Atchison he obtained a doctor’s prescription, then checked into the Lindell Hotel where he had to be helped to his room on the second floor. When he failed to appear for supper an employee was sent to check on him but received no response.

Mr. Lugton went back with young Bruce and helped him through the transom into the room. Bruce opened the door from the inside. Lighting a match they saw poor Scarbrough sitting in a rocking chair, his arm resting on a washstand, his face to the open window looking west, cold, pale, dead.

All alone, and as if looking across the cold wintry distance that separated him from his home and wife, child and his aged mother, he had passed to another world than ours.

With high drama, pathos and a hint of mystery - that’s how a real newspaperman checks out of a hotel. Well done, Mr. Scarbrough.

Both pamphlets pictured here remain available to this day. The History of Jewell County is sometimes offered as a free download, while A History of the New Gold Discoveries can be read online at Google Books. A printed copy of the latter which can be held in the reader's hands and stored on a private bookshelf can cost as little as $20, merely twice what Mr. Oakes was willing to pay in 1883 - so, a bargain!