I’ll say one thing in my favor - I make writing family history look hard.

There was a mystery to be solved on Friday, and I toiled over it during idle minutes between job-related duties several times throughout the day. The resulting blog entry was not an attempt to lead anyone on. I didn’t know the solution at the outset of writing it and honestly did change my mind toward the end of almost every paragraph before finally landing on an answer I couldn’t knock down. It was the sort of problem the boys at “Antiques Roadshow” would have wrapped up in 60 seconds or less. After putting the page and myself to bed, I got up, re-read it and discovered so many typos, word fragments and poor word choices that I spent much of Saturday morning trying to mend it or at least make it more intelligible.

Already 300 words over my self-imposed limit of a thousand, I left out the answer to the burning question that should have simmered in every reader’s mind (all twenty of you): Did Jake Stofer get to see the real “Buffalo Bill” perform at the Sells-Floto circus in July 1915?

I won’t keep you in suspense any longer: yes he did. Continually in need of cash toward the end of his life, William F. Cody took a $20,000 loan from an unscrupulous businessman named, Harry Heye Tammen, one of the partners in the Denver Post, a tawdry, sensational rag in that day. Cody confessed that it was the worst mistake he ever made, and one that broke his heart.

Tammen and Frederick Gilmer Bonfils were also the men behind the Sells-Floto Circus, a traveling show with a title concatenated to suggest that the partners’ Floto Dog and Pony Show, named after the Post’s popular sports editor Otto Floto, had merged with the Sells Brothers Circus. It hadn’t, exactly. Willie Sells’s act had been added to the show, perhaps chiefly for the luster his name would bring to the posters.

Harry Tammen was more interested in collecting names than talent. By 1914 Cody discovered that not only was his show in thrall to Tammen until the debt was paid back, but he no longer owned the sobriquet “Buffalo Bill” - Tammen did. In 1914 and 1915, the newly-merged entertainment toured under the banner “The Sells-Floto Circus and Buffalo Bill’s Original Wild West.” A trouper to the end, Cody proudly recalled that he never missed a show. When the circus played at North Platte, the local Tribune heaped on the praise.

The horse back riding, the trapeze performing and acts of contortion were up to the highest standard, and the show as a whole was complimented by everyone. Colonel Cody was given hearty applause as he entered the arena, and in his address he paid a compliment to North Platte and its people and to his old friends.”

The very next sentence should dispel any notion that the story was a prefabricated puff piece provided by the Post’s copy editors: “At the evening performance there was fairly good attendance.”

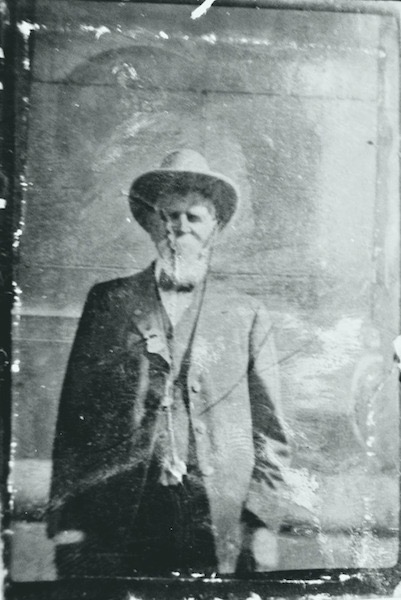

In short, yes, if the picture above is what I think it is, Jake Stofer saw William F. Cody in one of his final appearances as “Buffalo Bill,” before standing in front of a poster of Cody and having a photo taken. That it’s a terrible picture is beside the point. It’s like a cheaply-made trinket purchased at the Louvre gift shop. The crude likeness may not look much like Napoleon Bonaparte, but you were at the Louvre when you bought it. Every time you see it, you’ll be reminded that you were there once. That’s what’s important.

When Cody succumbed to kidney failure two years later, Stofer may have taken out the old tintype and held it up to the light before placing it back in a drawer of treasured mementos picked up during his life as a Civil War Soldier, White Rock pioneer and local cattle baron.

Jacob G. Stofer died after an attack of gallstones in 1924. When I saw one of the pictures Dale Ann Johnson sent a few days back, I was pretty sure I was seeing another sort of souvenir, one from Jake's funeral at Scandia - a group shot of his closest family members, most of them dressed in mourning garb. Jacob died leaving a widow and six surviving children. Is it only a coincidence that there are seven people posing in front of the Stofer house?

That’s obviously Ben Stofer and Jake Jr. on the back row, with, I suppose, their brother Bursy between them. It’s clearly Mary White who’s standing next to her mother Nancy on the front row, though I’m not sure about the two ladies flanking them. The other two daughters born to Jacob and Nancy Stofer were Rose Septer from Republic, and Emma Granstedt, the mother of Irene Granstedt, a young lady a few years away from a film career under the stage name “Greta" Granstedt. Since the two sisters were born a decade apart and Rose was the firstborn with only a few miles to travel, the woman on the right seems a prime candidate for Rose. That doesn’t necessarily mean she is Rose, nor does it make the woman on the left Emma. If it is Emma, she may have suffered a wardrobe malfunction* earlier in the day. She does seem almost old enough to be Emma, who turned 43 that year. I hesitate to say for sure that Emma even made the long trip from Mountain View, California, for her father’s funeral.

That is, I did hesitate until something at the left-hand edge of the photo caught my eye. I wonder if the picture was snapped by the same family photographer who would shoot one of Ben and Mary Stofer with their grandkids in 1934, leaving plenty of room on the left for a plot of empty ground, a dilapidated corn crib and a scythe. Anyway, there’s not enough information to lead me to bet real money on it, but I’m halfway convinced that we can see a 16-year-old future Greta Granstedt peering around the support post of the front porch, gazing in impish bemusement at her funny old straitlaced relatives. If it’s not Greta, then whoever she is, she oughta be in pictures.

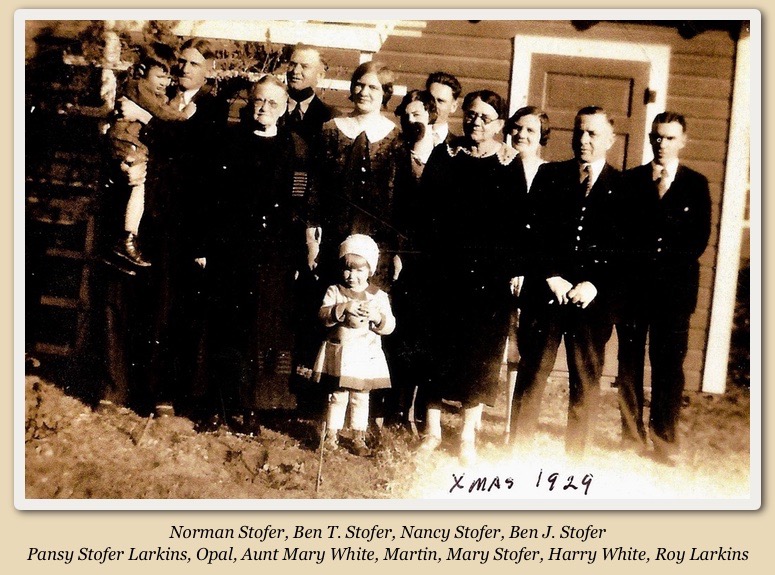

Dale Ann shared another picture featuring a few of the same people, a photo that should have been a reminder of a joyous Christmas gathering five years after Jacob’s funeral. However, what made the celebration special enough to merit another group portrait was that it would be the family matriarch’s last, and everyone knew it. Nancy Stofer was gravely ill and would join her husband in Riverview Cemetery by February.

Dale Ann’s grandmother Opal made things easy for me, listing the names of most of those in the picture on the back. Most, but not quite all. There are twelve people but eleven names, and the names are arranged in a slightly eccentric order, as if intended to be helpful to people already acquainted with the family, not those of us who are only peeking around the corner. I think I understand who’s who here, except for the little girl stationed front and center. If anyone can name her, I'll split half my winnings from the Greta Granstedt bet.

* The reason for Emma’s appearance finally occurred to me (see “Grief Encounter”)

Photographs provided by Ashley Gresham and Dale Ann Johnson