A few days ago, my friend Barb from Escondido forwarded news about an app that holds considerable promise. Over the past few years, I’ve turned to findagrave.com with greater frequency, as the site grows ever more useful. For years it seemed to be a low-rent home to scattered pictures of gravestones provided by thoughtful descendants. One day I noticed that some methodical contributors had performed photographic surveys of whole cemeteries, especially small ones, such as the one at White Rock in Republic County, Kansas. Lately, the site has become populated with photographs of the departed and their kin, obituaries, sometimes even small biographies. It boasts nothing to match the card catalog at Ancestry, but if you’re looking for information on an ancestor, its ratio of likely candidates to long-shots is undoubtedly better. It’s also free.

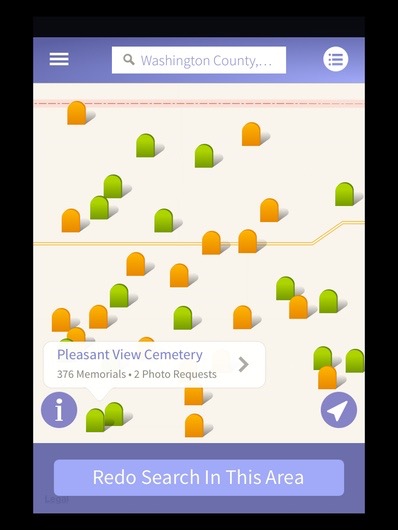

The app which Barb alerted me to is also free, although for the moment it works only on Apple iOS devices. Designed for the iPhone, that is where it truly shines, but an iPad will do in a pinch, and an Android version is in the works. Buffed to an elegant polish by the folks at Ancestry, the app is a front-end to the findagrave database, with some neat touches that take full advantage of mobile devices. There are also quirks. Using your iPhone’s current location, you’ll be greeted by a simple map with tombstone shapes identifying nearby cemeteries. Touch a tombstone icon, and you’ll see what’s available there, usually a listing of internments and memorials, some with accompanying pictures. If there are no pictures of headstones, you’re invited to provide the first one by touching the camera icon. There’s also a list of photo requests for the cemetery - you know, if you wouldn’t mind, as long as you’re already there.

I can sense that a website which has been growing lately by leaps and bounds is about to take off geometrically. The ease with which people can fill in the blanks, almost assures it. As for me, after playing with the new toy for a while, I went to my computer to literally fill in some blanks.

For some reason, Lewis Castle and J. C. Roberts were missing from the database of the Vining Cemetery in Washington County, Kansas. They were two of the six buffalo hunters attacked by Indians in Jewell County, Kansas, in May of 1866. Both names appear in a canvass taken in the 1970’s, so their markers may have become illegible since then. The men’s headstones were provided by the U.S. Government many years after their deaths, and contained only sparse details about their military rank and dates of service during the Civil War.

By the way, the search engine was rather finicky about what I called the cemetery at Vining, Kansas, preferring that I use its official name, Pleasant View Cemetery, which, inconveniently, seems to be the most popular name for burial sites in Kansas. It also refused to acknowledge that I had correctly typed the location, Washington County, KS, USA, insisting that I select it from its list of recommendations, where it was spelled exactly the same way. Perhaps the app believed that I was trying to take its job.

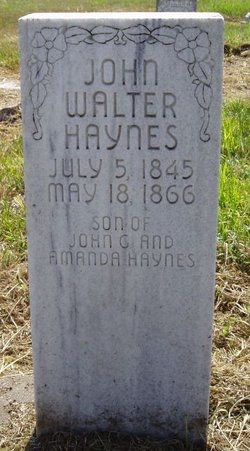

John Walter Haynes is now the only one of the massacre victims from Clifton in the Vining Cemetery with a photo on the site. The internment of Castle and Roberts among various members of the Haynes family, where the 1970’s canvass places them, probably means that family patriarch John Griffin Haynes provided plots for the men from Clifton. The final resting place for Tallman (His name may have been Tollman) is unknown, but the two Collins boys are buried in Concordia's Pleasant Hill Cemetery.

I often refer to them as “boys” although their shared headstone at Pleasant Hill indicates that both were in their late 20’s when they were caught up in the desperate flight of the Castle party from attacking Indians in 1866. The headstone is modern, and contains the helpful inscription, “Killed by Indians, Still Remembered.” Their father, William C. Collins, who was born in England, is also buried there, and besides a picture of his monument there is also a concise bio of the man who died ten years after his two sons were killed and mutilated. It contains the sort of information that can make findagrave.com so valuable.

He immigrated to the U.S. with his parents before 1837. He drove an ox team from Quincy, IL to Kansas in 1866 and homesteaded north of Concordia near the trading post of Sibley. He was Justice of the peace in Cloud County and performed most of the early marriages there. He was called "squire" in newspaper articles and was also Sheriff. He was killed when a team of horses ran away with a wagon.

We now understand that John and Will Collins were slaughtered almost immediately after alighting at Lake Sibley from Quincy, Illinois. The chase that ended with their deaths was glimpsed by Orel Jane Lovewell in mid-May of 1866, perhaps as little as two weeks after the Davises and Lovewells arrived in Republic County. The great wonder may be that after such a greeting, all three families decided to remain in Kansas.