Tom Robinson paid me a nice compliment on my last column, “Closing the Gap," commenting that I could take a thread and make a jacket out of it. At least I think he meant it as a compliment. He kindly did not point out that my jacket was woven largely out of invisible threads. After all, I had taken nearly a thousand words to admit that I couldn’t identify anybody in a family portrait taken over a hundred years ago. Still, I like to keep in mind that old anecdote about Edison chalking up his latest failure to produce a practical light bulb as successfully ruling out another bad idea.

To recap the concept in less than a thousand words: Tom passed along a portrait identified by his great-grandmother as “neighbors,” evidently a family that lived near the Robert F. Robinson farm in Jewell County late in the 19th century or early in the 20th. There’s a bald-headed and bearded father, a mother who seems to be about ten years his junior, and nine children, five or six of whom are boys. Two of the children are very young.

On the chance that I might get lucky, I looked up Tom’s great-grandfather in the Kansas Census, and then searched for nearby families with nine or so children, paying special attention to those with more boys than girls. The first large family I encountered living near the Robinsons in 1895 were Pontus and Ingeborg Ross with their ten offspring. Boys did predominate in the Ross household, but I have a picture identified as Pontus and Ingeborg, and in spite of the fact that Pontus also sported an ebbing hairline, the Rosses didn’t otherwise resemble the adults in that mystery portrait. Other nearby farmers with gaggles of children who briefly competed for my attention include James McRaith, John Quick and George Dart. However, while a 30-ish mother sitting in the midst of her nine children might strike us today as a reality TV show in the making, it was a thoroughly commonplace family scene not that long ago.

When was that picture taken at the Mackey Studio in Superior? One useful clue might be provided by the name of the studio. Born in the middle of the 19th century, Thomas M. Mackey had established himself as a portrait photographer in Omaha by 1890, moving to Nuckolls County at the turn of the century, or perhaps a few years earlier. Although there are glamour portraits bearing Mackey’s imprint that seem to date from the era of the late teens or early 1920’s, this one feels firmly Victorian. My most confident guess is that it was taken between 1895 and 1905.

The year is hard to pin down any closer than that from the clothing the subjects are wearing, and not only because I’m no expert on year-by-year fashion trends in rural Kansas. Clothing was not cheap in bygone days, people hung on to it for decades, and children often grew up wearing hand-sewn garments and antique hand-me-downs. The head of household may have bought that suit coat and vest a week before he posed with his family, but considering how tightly those vest buttons are cinched, it seems more likely that he had worn the same outfit to his wedding.

There are websites that provide helpful information for dating 19th century apparel, and while visiting one a few days ago I made an amusing discovery concerning another photo on this site.

A year and a half ago Dave Lovewell sent me a photo of his grand-uncle Simpson Grant Lovewell, a picture taken at Warwick when Grant was 14. We agreed that the photo probably commemorated the young man’s graduation from the eighth grade, which would have marked the end of his scholarly endeavors. Since Grant, the eldest of Thomas Lovewell’s boys, was born in 1869, the year must have been about 1883. I joked at the time that he could have slipped into the outfit in October to go trick-or-treating as Zorro (a deliberate anachronism, since Johnston McCulley didn’t invent the masked horseman until 1919). It did occur to me at the time that Grant’s coat was buttoned with the same cavalier flair seen on some of the G.A.R. vets in that 1885 reunion photo taken at Republic City. While I had once assumed that these men were wearing their old Army coats, and the top button was the only one that would still meet the corresponding buttonhole, it now seems that this was once considered stylish, a way of making a dress coat flare out at the waist like a cape.

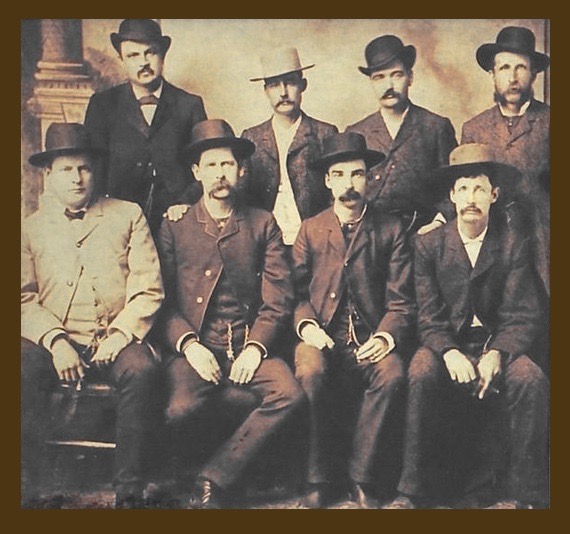

This idea was confirmed by one of the men's fashion websites I consulted, which contained a picture of some gentlemen demonstrating the avatar of manly fashion circa 1883. It’s a familiar photo, known as the “Dodge City Peace Commission,” featuring some genuine Western celebrities including Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp, who threw their support behind their old buddy Luke Short in a dispute involving his interest in the Long Branch Saloon. Bat is on the back row, second from the right. Wyatt is seated next to the man in the white coat.

So, even if Grant Lovewell couldn’t trick-or-treat as Zorro that year, he could have dressed up as Wyatt Earp. Of course, he would have looked exactly like every other well-to-do young man-about-town in 1883 wearing his Sunday best.