Most evenings I read for a while in bed before hitting the light switch. Lately I’ve continued to plow through Ronald Becher’s 1999 “Massacre Along the Medicine Road” a few pages at a time. Currently I’m learning about the weeks when the initial shock began to subside after that devastating series of Indian attacks along the Little Blue and the Platte in early August 1864.

Newspapers could get down to the business of trivializing what had happened, pointing fingers at the Army for their slow response, and poking fun at the new German arrivals in Nebraska Territory. Besides hinting that their artillery piece was suffed with sausage and sauerkraut, one paper dubbed a fort built by beleaguered immigrants at Grand Island City “Fort Nicht-komm-heraus” (“Fort Don’t-come-out”). Another hurriedly-constructed barricade at Columbus was given a name which the paper, with tongue in cheek, suggested might have an Indian origin.

In an incredibly short space of time, one half of the population had run away, and the other half had reared that prodigy of military architecture, Ft. Sockittoem (how appropriate and euphonious are Indian names). Ft. Sockittoem is still plainly visible to the passer by.*

I was startled to come upon what I always considered a modern expression in an 1864 paper, and couldn’t stop thinking about it later, imagining George Armstrong Custer rallying his men for their final stand by drawing his saber and shouting, “Sock it to ‘em boys!” Or, as the enemy closed in, could he have prefigured a certain jowly future president who, 90 years after Little Big Horn, took to the airwaves on “Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In” to establish his relevance to young voters by inquiring, “Sock it to me?” If Arthur Penn had put those words in Custer's mouth in his 1970 film “Little Big Man,” critics would have flayed him for using a blatant anachronism for a cheap laugh. And yet, it was apparently current slang in 1864.

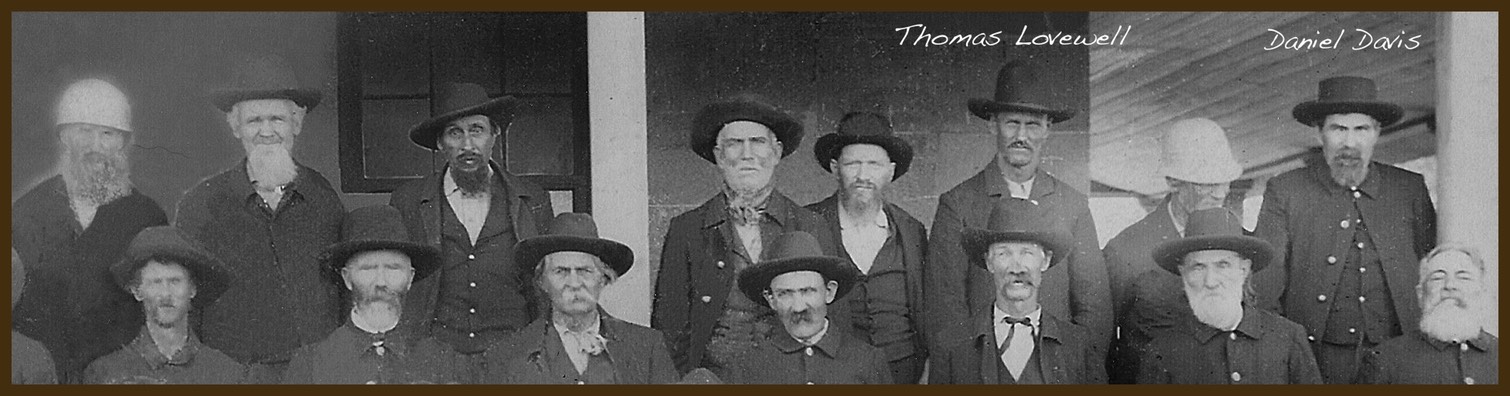

Time and space also appear to be out of joint in the Civil War reunion photograph, which, as I suggested in my last posting, may have been taken a year or two later than I first thought, and could have been snapped in northern Kansas instead of at Langdon in Reno County, west of Wichita.

What’s wrong with this picture? The headgear on two of the veterans make them look less like Civil War veterans than refugees from “Gunga Din” or “Tales of the 77th Bengal Lancers” or a pair of itinerant polo players. It transpires that the “summer sun helmet” which was standard issue for British troops fighting the Sepoy Rebellion in 1857, was also adapted for use by the U.S. military in the 1880’s. A cork dome covered with cotton twill, variations of Model 1880 were adopted by various National Guard units and marching bands. The two helmeted veterans posing for a group portrait with their comrades were probably musicians on hand to provide martial airs for a local Civil War reunion.

Where and when was the picture most likely taken? The Davis descendant who thought the photograph might have been a memento of a reunion at Langdon was unaware of Daniel’s long residence in the White Rock valley, but knew that his last years had been spent in Reno County, where he was buried in 1898. A few years ago I was certain that the reunion must have happened in 1885. My reasoning turns out to have been wrong, though 1885 may have been a lucky pick, exactly right or off the mark by only a year or two at most.

The picture has undergone wholesale retouching at some point in its history, erasing telltale details on the building behind the attendees. However, on the extreme right side of the photo, instead of the clapboard siding we might expect to see, we can make out the seams of large limestone blocks of the sort used as building material at White Rock. When I stopped looking specifically for G.A.R. encampments, I found that there were a number of soldier reunions held within a few miles of White Rock City between 1885 and 1887. These were usually three-day affairs with music, games, mock battles, and orations by local dignitaries. In 1885 there was a reunion at Scandia where Col. M. M. Miller gave the address. Reunions were held at both Belleville and Mankato in 1887. I was especially interested to learn that in September 1886 the Republican Valley Association of Soldiers and Sailors held their first annual reunion along the state line between Hardy, Nebraska, and Warwick, Kansas, at Camp Sherman, only a few miles from the already-fading settlement at White Rock.

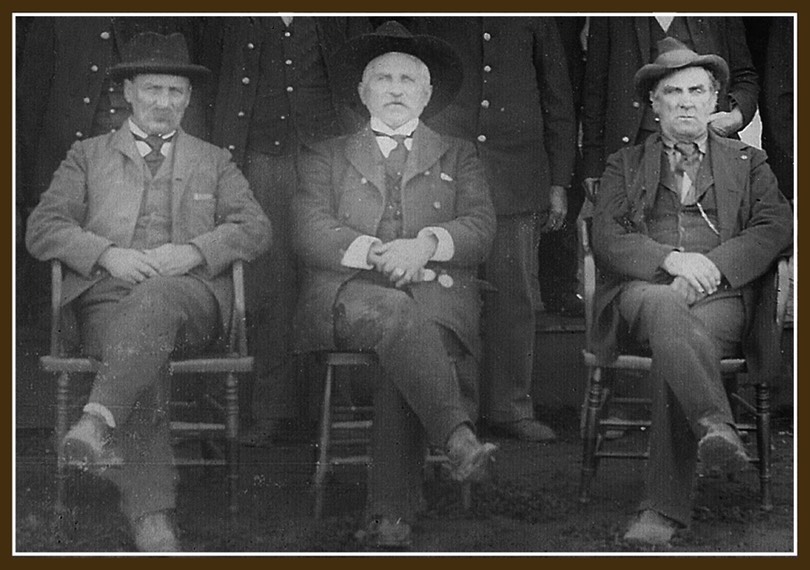

The identification of dignitaries on the front row of the group portrait would provide valuable clues as to the time and place of the side-trip we seem to be witnessing. If any of the the men turns out to be Col. Miller from Clay Center, then the reunion might have been the one held in Scandia in 1885. If one of them is Judge Borton from Clyde or E. B. Towle from Belleville, then it was most likely the Republic Co. Old Settlers Reunion at Belleville in 1887. Speakers for the 1886 affair between Hardy and Warwick included A. B. Wilder of Scandia, J. F. Close from Belleville, and Rev. J. B. Alumbaugh of Warwick. Unfortunately, I haven’t found likenesses of any of those distinguished gentlemen to compare with the faces in the reunion photograph.

Such reunions were heavily attended by former soldiers from the region. The picture we have, thanks to Richard A. Davis, CPA, seems to record a visit by some august guests to a town near the reunion site, which several local citizens and reunion attendees are proudly showing off. We could be seeing a photo-op on the streets of Warwick or Hardy. However, the presence of Thomas Lovewell and Daniel Davis among the crowd seems to increase the odds that this may be the only photographic glimpse I’ve ever seen of White Rock City.*

*As I discovered in time for the very next blog entry, the site of the picture is apparently Republic City, now known simply as Republic. The reason so few soldiers are included in the group shot is that the occasion was not a reunion or encampment, but the regularly scheduled meeting of the local G.A.R. post.

*Ronald Becher implies that “sock it to ‘em” may have been another way of saying “make ‘em pay,” but in a very literal sense. The merchants at Columbus were known for using almost any pretext to jack up prices on their merchandise.