Readers who were introduced to the story of Thomas Lovewell in the latter half of the 20th century found the tale of his year-long search for gold in Alaska presented as his last hurrah at the age of 73, the capstone of an extraordinary life of adventure.

When Thomas popped up among the crowd at the Old Settler’s Reunion in the summer of 1900 and then ascended the stage to give an account of his recent travels, many in the audience were surprised to see that after so many months without any news from the old pioneer, he had actually made it back alive.

Although that’s the way the story is presented in Sherman Lee Pompey’s The Wolf and Little Wolf (1962), Gloria G. Lovewell’s The Lovewell Family (1979), and Roy Alleman’s The Bloody Saga of White Rock (1995), it’s not quite what happened. If some onlookers did express surprise at Thomas’s reappearance in 1900 it may have been because Thomas had only embarked for Alaska in May, and here he was already home again in August. The last time he had succumbed to gold fever he was gone six years.

Furthermore, the voyage to Cape Nome did not cap anything. Apparently it only whetted Thomas Lovewell’s appetite for travel and prospecting. What ensued was a string of eight annual trips to Wyoming, usually made by horse and wagon, often with family members, neighbors and friends in tow to join Thomas in scratching the earth for those elusive traces of precious metal.

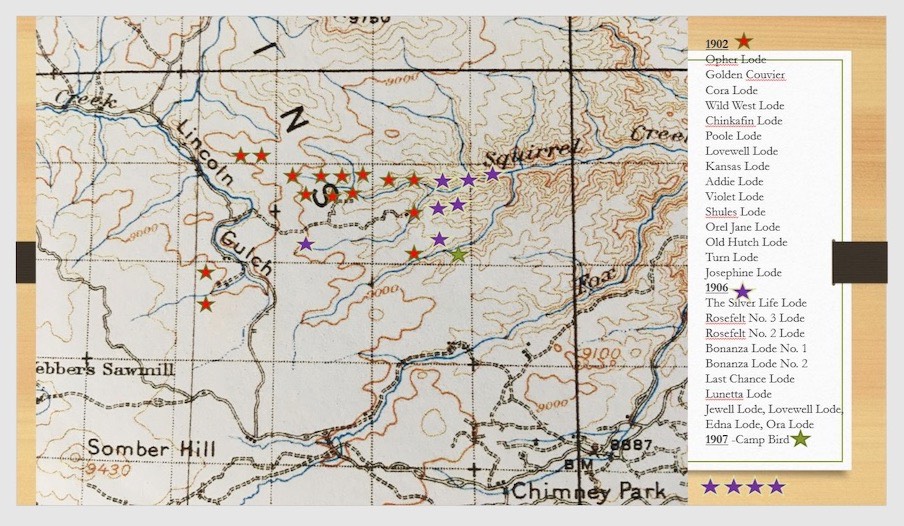

We have concrete details about this phase of Thomas Lovewell’s story thanks to on-site research by his great-great-grandson Phil Thornton. Phil has spent nearly a decade’s worth of summers investigating what went on in Lincoln Gulch between 1901 and 1908.

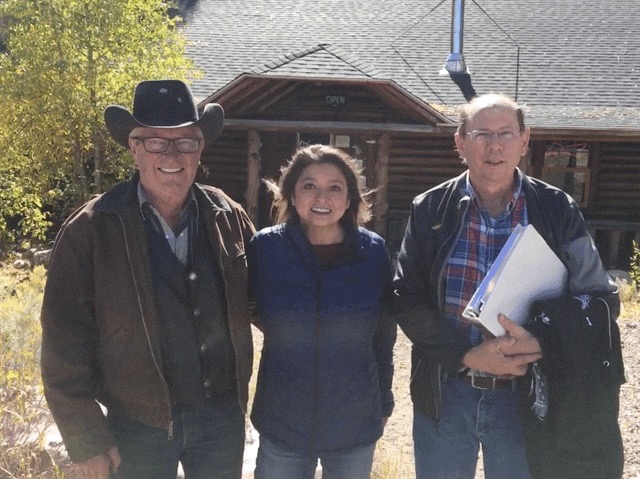

With the assistance of Marvin Brandt and the late Ana Brandt (both pictured here with Phil, who clutches his maps and notes) as well as Jane Nelson from the Albany County Historical Society, Phil has managed to pin down the location of several claims explored by Thomas Lovewell and his associates from Kansas over a century ago. The group clearly thought they were on to something, and apparently enjoyed enough success to keep them digging.

Phil also believes that an archival photo (below left) from a geological survey early in the 20th century contains a glimpse of a cabin and corral erected by the Lovewell party along Squirrel Creek. This is undoubtedly the spot where the visitors from Jewell County camped every summer, and the cabin may be the same one damaged by an accidental dynamite explosion in 1903 and later repaired.

The calamities which beset Phil during his own investigations were all of the natural kind, chiefly floods and forest fires. And rain. Lots of rain. The kind of weather that made even Thomas Lovewell decide to come home early one year.

Launching a drone to capture an eagle's eye view of the area during a pelting rain (pictured at the bottom of the page) reveals an overwhelming sameness, a landscape that could easily swallow up unwary newcomers and leave them wandering around in circles. It’s what might have happened to Phil if his guide hadn’t thought to bring a compass and take a reading before they began their walking tour.

It must have been a treat for Thomas Lovewell to show his family the raw landscapes he had first encountered in the 1850’s, before all railroading and the mapping and platting and homesteading. The trek through southern Nebraska and northern Colorado on the way to Woods Landing was pocked with landmarks the old man surely insisted on pointing out to his children, probably every summer.

There was Fort Kearny where he recuperated from illness on his trek home from California, and the little fort near Gothenburg where he spent the night on the eve of a series of vengeful attacks along the trail to Kearny. Next came Julesburg, once sacked by Cheyenne warriors, and where a nearby sod barricade was put under siege and nearly overrun.

When Eugene Ware, who chronicled the period in 1865: The Indian War, returned to Julesburg, even he had a hard time figuring out exactly where that old sod fort had once stood. Citizens of Gothenburg could proudly point out the site of the former Pony Express Station, but seemed not to know that there had been a fort, fiercely defended against overwhelming odds, years after the Pony Express had come and gone.

For old-timers like Ware and Lovewell, there was a history that seemed to be in danger of being forgotten as the country plunged relentlessly ahead into a new century of progress. Better tell the story again next summer, just to make sure they remember.