My first encounter with a 19th-century family portrait involved one which was hanging on the wall of a friend’s living room. It was a picture of her great-grandfather, a pitiless-looking bearded man named Bannister, who she said had been a lawman in the Southwest. The portrait was mounted in an oval frame that was a few inches too large for it. Strips torn from vintage newspapers had been arranged around the edges of the picture as a sort of creative matte, which also added an aura of antiquity to the keepsake.

“It’s the only photograph he ever posed for,” she said.

“That's no photograph,” I pointed out, scrutinizing the eyes of the portrait and trying to sound knowledgeable. “Charcoal or conté crayon with maybe an ink wash.”

“Really?” She seemed skeptical. "Some other relatives have smaller copies. I think they were all made from the same negative.”

I shrugged and thought nothing more about it until many years later when Cousin Barb told me about a pair of individual charcoal sketches of a man and a woman that had been stashed away in a relative's attic. She said the female subject resembled the woman in a photo that had long ago been identified as Thomas Lovewell’s daughter “Julaney" seated beside her second husband, John Robinson. Either Barb or her sister Bev managed to center each of the charcoals on a flatbed scanner and send me copies.

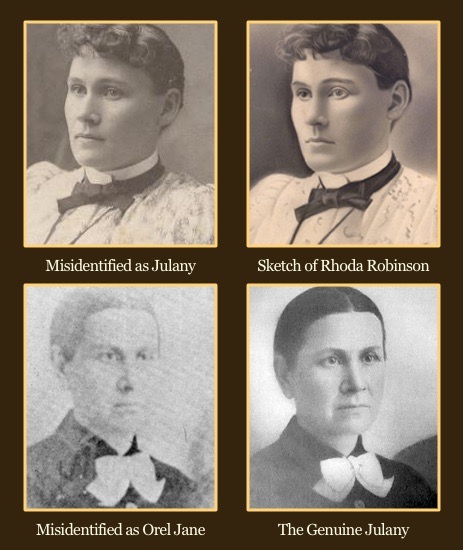

A glance at the sketches alongside the old “John and Julaney” family portrait should be enough to convince anyone that the likeness of the woman was made by a freehand artist who used that photograph as his guide. The pose and facial structure are identical, with one exception which we’ll get to later. Even the lady's hair style and clothing have been reproduced exactly. Since the male subject of the charcoal sketch was soon shown to be Charles Overman, the first husband of Rhoda Robinson, Rhoda became our chief suspect for the woman in the sketch, as well as the woman misidentified in the photograph as Thomas Lovewell’s daughter.

Rhoda Robinson was Thomas Lovewell’s niece, the daughter of his sister Hepsabeth. She was also Barb and Bev’s great-grandmother.

I’ve learned since my run-in with a family heirloom many years ago that photographic enlargements from the 19th century are rare. Portrait cameras were loaded with large-format film. The cabinet-sized pictures which a photographer’s clients liked to display in their homes were contact prints, always the same size as the original image from the camera. There was a cumbersome device for making enlargements, an apparatus that resembled a tracking solar telescope which was usually mounted on a rooftop. The resulting enlargements must not have been anything to shout about, because they were usually painted over with layers of dyes and chalk until very little of the original photograph was visible. The finished product was often labeled a “Crayon Portrait.”

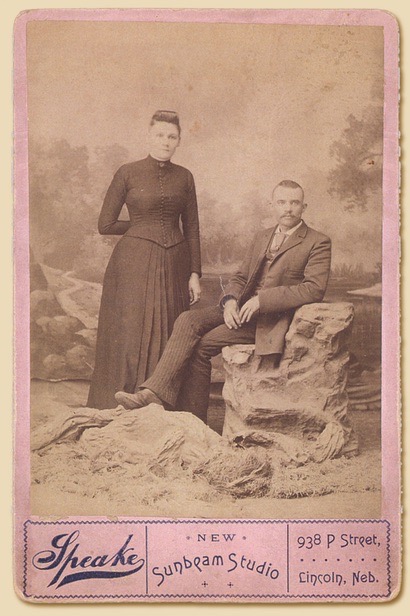

The only other way to obtain an enlargement suitable for framing and hanging in the parlor, was to hand a photograph to someone who knew how to wield a stick of charcoal and say, “Draw it bigger.” That’s what Rhoda Robinson Overman did after her husband Charles ended his suffering in 1907 by pointing a pistol at his chest. She commissioned separate portraits showing the couple in happier days, long before her husband’s unnamed malady set in. She gave the artist a copy of their 1883 wedding picture taken in Lincoln, Nebraska, which contained her favorite likeness of Charles.

However, Rhoda instructed the artist not to use that horrible picture of her standing next to her husband, her hair done up in the sort of massive curl most of us today associate with Justin Bieber or Buster Poindexter. Instead, she showed him a pose of her looking serene and delicate beside her brother John, a photograph taken when she came to White Rock for a visit. She and John had been separated as children after their father’s death, and a family reunion made an excellent excuse to dress up and have a picture made.

That must have been Thomas Lovewell’s thinking in 1893, when he was reunited with his long-lost daughter, known for most of her adult life as Julia McCaul, but memorialized on her headstone as Julany Robinson. It may have been after he lost her to cancer the following year that he wanted something bigger than the cabinet photo to validate their brief time together. One has to wonder whether the same urge struck Thomas and his niece independently, or if on a trip to visit her uncle she had been touched by the sketch of a father and his lamented daughter, and wanted something similar to commemorate her love for her late husband.

The two got mixed results for their money. The sketch of Charles Overman is by far the best of the four likenesses, which must have been enough to suit his widow. The artist did a stylish job with Rhoda’s tendrils of hair and the pattern on her outfit, but completely misplaced the orbit of one eye (Feel free to take your pick), giving her a disquietingly robotic stare. The drawing of Thomas is at least recognizable, if long-faced and dyspeptic, while the resemblance of the sketch of his daughter to her photograph is so minimal that for many decades the artwork has been thought to represent Thomas’s wife "Orel Jane in her younger days.” Unfortunately, the picture doesn’t look much like Orel Jane Lovewell, either.

But, as they say, it’s the thought that counts.