When I received the Homestead records for both Daniel Davis and Thomas Lovewell from the National Archives a few years back I was puzzled for a while about the dates written on their Homestead applications. Daniel Davis signed his name to the paperwork for his claim near the mouth of White Rock Creek in mid-January 1867, while Thomas’s application for a quarter-section on the western edge of Republic County was signed two weeks later at the very end of the same month. Since Daniel was challenging a prior claim by a settler who seemed to pull up stakes after a massacre of buffalo hunters in southern Jewell County, Thomas had to testify as a witness in his brother-in-law's case. In other words, Thomas made the trip to Junction City and back twice within two weeks.

The men may have used the farm of Daniel’s parents near Clyde as their staging area for these journeys. Just getting to Clyde from White Rock was a long day’s wagon ride. Junction City was another sixty miles from Clyde, a distance which would have taken two full days to travel. I wondered why they had made two separate trips instead of combining the two filings. Then I remembered that there was an old family story about the Lovewell/Davis cabin being used as an informal post office. Ah, I thought, they may have been dropping into Junction City anyway, perhaps even more often than once every two weeks, handing off outgoing letters and picking up incoming mail for Clyde and the new settlements along White Rock Creek. Perhaps they were even making money at it.

Thomas Lovewell’s great-grandson Dave Lovewell has found evidence in the Executive Documents of the House of Representatives from 1858 and 1859 that those trips to Junction City were not Thomas’s first go-round with a mail sack.

In Marshall County in 1858 Thomas Lovewell placed five bids on mail routes across the northeastern part of Kansas Territory. One of these was for carrying mail between Lecompton and Marysville, a distance of 104 miles each way, three times a week. Thomas’s bid of $4,747 was only $300 more than the winning bid and $4,000 lower than the highest bid received. Another lucrative contract would have been the one from “Leavenworth City to Dyers, 150 miles and back, once a week.” Thomas was in the middle range of the bidding at $2,987, but no contract was awarded to anyone. Perhaps even the low bid of $2,000 was considered too pricey for one mail run a week. He was within about $200 of winning the weekly 100 mile trek from Fort Riley to Marysville and back, and even closer to winning the route between Fort Riley and Vermillion City, service that was suspended before a winner could be declared. The government may have decided that one weekly delivery between Fort Riley and Marshall County was enough at these rates.

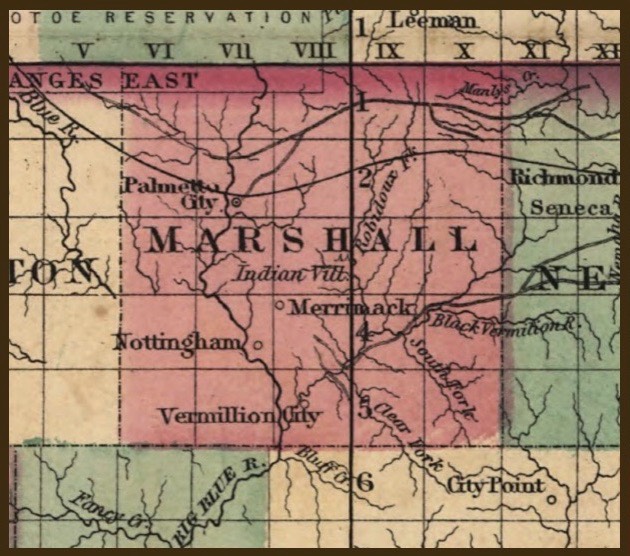

Thomas’s only winning bid was a measly $149 a year to haul the mail back and forth once a week between the now-defunct towns of Vermillion City and Nottingham, which lay 14 miles apart in south-central Marshall County. He had been willing to make the trip between Marysville (shown on the map as Palmetto City) and Nottingham for only about $50 more, a total of $197.50. In submitting his winning offer, Thomas underbid his neighbor, John D. Wells, who was to Marshall County what Thomas Lovewell was to western Republic County, a founding pioneer spirit.

His winning bid was for a one-year contract ending at the close of April 1859, a time-stamp which may tell us when Thomas left Kansas Territory to relocate his family in Iowa in preparation for his journey to Pikes Peak and beyond.

It is less interesting to me that he was awarded only one out of five government contracts, than the fact that he was bidding on five of them simultaneously. Thomas was apparently ready to pour some of his winnings from land speculation in Iowa in the early 1850’s into a bold entrepreneurial venture that might have made him rich. If he had been awarded one or two of the big prizes he would have needed to buy or rent wagons and a stable of horses and hire employees. Perhaps he thought of the new business as a way to lure his brothers to Kansas as partners or members of his crews.

I’ve always wondered whether stories of Thomas taking six yoke of oxen to Pikes Peak and poking about in the San Francisco real estate market were partly just so much bluff talk. No, this was a man with big dreams.

Detail from 1858 Colton’s Kansas and Nebraska, courtesy Library of Congress

Unfortunately, according to Marshall County researcher Keith Jones, the map shows Nottingham lying northwest of Vermillion City, when it actually lay to the northeast, about fourteen miles up the Black Vermillion.