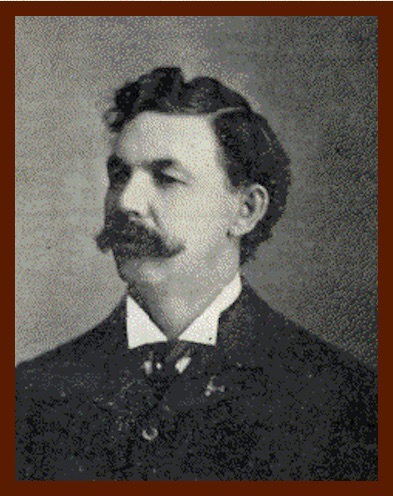

Born at Pont-y-Prydd in Glamorganshire, Wales, in 1850, Gomer Taliesin Davies came to America in 1863, lost a leg to a mining railroad accident in Iowa, married Catherine Powell, and followed a meandering trail into Kansas by 1882. In 1883 he bought the Republic City News, serving as editor and publisher for a decade before moving on to take the helm of the Concordia Kansan.

In my last blog entry I shared quotes from Davies’s condemnation of scandalous goings-on around White Rock in 1886 (see “Dirty, Stinking Scandals”). Gossip had been resurrected concerning a man named Jacobs, who was said to have committed murder some years previously and hidden the body in a well. Whispers about this supposed killing began anew when Jacobs deeded his farm and some property in town to the “notorious” Dr. Churchill, a one-sided deal arranged by local attorney Peter McHutcheon, whose office was set ablaze soon afterward.

If Gomer Davies expected his readers to connect the dots, or if the White Rock rumor mill had already done so, this story could be construed as a tale of homicide, blackmail, legal skullduggery and vengeful arson, a web of crime ensnaring some well-known citizens around White Rock. While he was at it, Davies also pointed out an unrelated scandal currently making the rounds involving another physician at White Rock, Dr. Batchelder, who accused his wife of having an affair with a neighbor from the upper crust of White Rock society. Mrs. Batchelder responded by scurrying off to her former home in Indiana.

Digging deeper into the newspaper archives of Republic County, I discovered that Gomer T. Davies’ sensational columns of June 1886 consisted largely of a rehash of old news. Putting aside the Batchelder soap opera, sinister tales about Wilhem Jacobs had been appearing in print for years, and had even led to a trial for libel in 1884, while Dr. S. J. Churchill had been the subject of scandal since May 1885 when the following terse snippet of local news appeared in the Scandia Journal: "Dr. Churchill in town two or three days, drunk.”

An arrest warrant was issued over another binge four months later. Kansas was now a dry state, but a few country stores had stockpiled a supply of “medicinal” bitters, including W. P. Brittain’s place near the Prospect Post Office, about a mile from the doctor’s home, and Dr. S. H. Churchill evidently prescribed a potent dose of it for his own use one aimless weekend in September 1885. The story became magnified after the storekeeper was charged with supplying intoxicating liquor and Dr. Churchill skipped town to avoid arrest.

Gomer Davies’s News was not even the first country paper to attach the honorific “notorious” to Dr. Churchill’s name. That prize goes to the Scandia Journal’s May 21, 1886 edition.

There is much excitement at White Rock over the machinations of the notorious Dr. Churchill, in securing a warranty deed to the Jacobs’ farm, together with the old man’s town property. By the request of some of the parties interested (not Churchill) we will not attempt to describe the muddle this week.

Judging from later events, other “parties interested” may have included lawyer McHutcheon and Mrs. Jacobs, Wilhelm Jacobs’ much-younger wife Catherine. In the 1880 White Rock census the 69-year-old Wilhelm, born in Germany, lived with his 40-year-old wife Catherine and eight youngsters, five of which were presumably the couple’s offspring, plus three that are noted as Wilhelm’s stepchildren - the two eldest, Kate and George, and the youngest, baby Wadsworth. A fractious relationship with the older stepchildren might explain an interview Kate supposedly gave (but possibly didn’t give) in 1884, resulting in the aforementioned lawsuit.

Gomer T. Davies did not take the bait in 1884, allowing himself to be scooped by two Scandia newspapers, one of which ran a headline characterizing the grisly affair as “Another Bender Case.”

Old man Jacobs, well known by many of our citizens and the traveling public as proprietor of the only hotel at White Rock for many years - a rookery and ruin to-day - has left the state recently, it is reported because a mystery was about to be cleared up. About twelve years ago a stranger stopped at the hotel one night for lodging and the next morning he was seen to go to the barn, but a few steps from the hotel, and from that time he has not been seen or heard from until very recently.

Kate, a buxom daughter of the old man was a prominent personage about the hotel in those days, now comes to the front with the statement that the father - old man Jacobs - killed the stranger on the morning of his disappearance and buried the body in the manure pile from which, after a time, it was removed and cast into a well which he afterwards filled up and built a corn crib over. It is also stated that some years after this reputed murder the old man killed his own son for fear he would disclose the secret. It is certain the boy died under suspicious circumstances.

There is considerable excitement about the matter and it is likely the well will be opened before our next issue and the above report corroborated or refuted.

The implication was clear. If a guest at White Rock’s only hotel went missing “about twelve years ago,” his murder must have occurred shortly after the “Bloody Benders” vanished from Labette County in southern Kansas. The Benders were a German family whose patriarch was described in 1872 as being about sixty years old, with a daughter named Kate. In the weeks after the Benders fled into the night, the bodies of a dozen hapless travelers were exhumed from the yard around their inn.

Although Davies’s did not cover the frenzy of gossip in his News in 1884, after congratulating himself on his forbearance, he did reprint the items published by the Scandia Journal and the Independent, but under his own headline “Very Near a Libel.” The headline referred to a trial conducted at White Rock after the stories broke and Jacobs sued for defamation. Having brought his readers up to date on the day’s gossip, Davies also covered the trial.

Desiring to get at the facts in the case we hastened to the scene of trial. It was not the editors, however, that were on trial, but the buxom Kate spoken of in the Journal, but both editors, Mr. Wilder and Mr. Tibbits were summoned as witnesses, and were on the ground. The result of the trial may be summed up briefly, the witnesses for the prosecution were examined and on motion of counsel for defendant the case was dismissed for want of evidence. The prosecution utterly failed to prove that the defendant had said anything in regard to the matter; thus it leaves the Scandia editors in a very peculiar position.

The well on Wilhelm Jacobs’ property was never dug up, as far as we know. After Gomer T. Davies took White Rock to task for its latest spate of gossip and scandal in 1886, the local press seemed to pay little heed to developments which in context are not just surprising, but almost stunning.

Told that Jacobs hoped to return to Germany, and might just do so later that year, no one thought it odd that he hadn’t been seen in the area for some months. In August his wife Catherine, who was not German, but had been born in Pennsylvania to French parents, served notice by publication that she was suing Wilhelm for divorce, citing habitual drunkenness as a cause. After a second publication in September her divorce was summarily granted in October, when she immediately married Dr. S. H. Churchill, the notorious town drunk of Prospect, and the man believed to have swindled Wilhelm Jacobs out of his land.