One of the delights in searching through old newspapers for historical tidbits is bumping into interesting things you weren't looking for. Once in a great while there’s a discovery so startlingly jaw-dropping that my jaw actually does drop a fraction of an inch.

A familiar sight on almost any page of a vintage paper is an advertisement for some cure-all or restorative nostrum. One of my favorite series of ads peddled a concoction devised to relieve the suffering of victims of dreaded catarrh. There really is a malady by that name, but despite sounding ominous, catarrh seldom leads to anything worse than a stuffy nose and a tendency to clear the throat while making unpleasant gurgling noises. If a myriad of worried newspaper readers were walking around with chronic sniffles, it was probably because of hay fever, and nothing they could swill was going to help, despite the proof of carefully-rendered drawings of “catarrh germs, greatly magnified,” which some sketch artist had apparently captured after staring through the eyepiece of a microscope at a droplet of snot.

While a diagnosis of stomach or liver cancer might sound several times more terrible than catarrh, bottles of "guaranteed cures” for even those maladies stood in rows at the local pharmacy, ready to come to the rescue. These usually took the form of various “bitters,” sweetened alcohol with the leaf of an herb stuffed inside the bottle to give the package a wholesome appearance. If swilling medicinal alcohol did not actually cure cancers of the stomach and liver, it at least must have hurried things along toward an inevitable conclusion. There was even an absolutely foolproof cure being advertised in the same pages to relieve male-pattern baldness: cocaine powder. It may have had no beneficial effect, but after a few treatments, patients probably stopped worrying about hair loss.

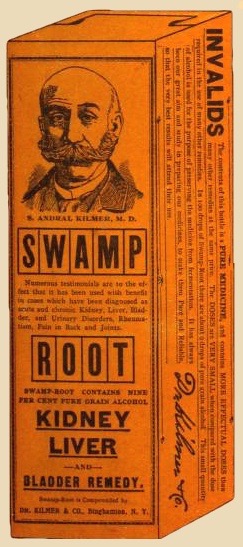

A few weeks back, while I winnowed the archives for information on banker, lawyer, and railroad tycoon Aaron S. Everest (see Everybody v. Everest), I kept catching a glimpse of a certain face staring at me from the outer margins of page after page. If Sylvester Andral Kilmer, M. D., (who apparently did not dust the dome of his head with cocaine powder) seemed to be everywhere, it was because, by the early 1890’s, he was.

His dourly reassuring face, some insist, was recognized by more Americans than that of the President of the United States. Though Dr. Kilmer had concocted his Swamp-Root Kidney, Liver and Bladder Remedy around 1878, his patent medicine business really took off when his nephew Willis Sharpe Kilmer joined the family business more than a decade later. Willis, a Cornell graduate, may have had a hand in producing the 1890 “Guide to Health,” which featured an engraving of Dr. Kilmer (“The Invalid’s Benefactor") on the cover and modestly proclaimed that it was being “Circulated for the Benefit of Suffering Humanity.”

Even though the company's advertising continued to pay homage to its founder, by 1892 his brother Jonas had bought him out and installed his own son Willis as marketing director. The Kilmer family lived on a palatial estate in their home town of Binghamton, New York, where they would eventually own a lodge, a yacht, and a stable of racehorses, including Kentucky Derby winner, Exterminator, most of the extravagant trappings paid for by the runaway sales figures of Swamp Root. Even the depression of the 1890’s did not diminish profits. Sales may have been down, but the family simply paid their employees less to bottle and package the stuff. Women who had made 10¢ per thousand units assembled at the Kilmer factory, made 7¢ per thousand in 1895.

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 finally interrupted the gravy train and forced the family to diversify. Thousands of bottles of the family elixir were seized, and a damning assay revealed the formula to consist of water, sugar, alcohol, and a negligible quantity of vegetable matter. Although the company would continue to sell Swamp Root, they were forced to divulge the ingredients on the packaging, and could no longer label the contents as a cure or remedy for anything, but something that might offer “relief.”

None of this information was particularly eye-opening. What did leave me agog was finding out that Swamp Root, rebranded as a “tonic” in 1907 is still being sold (on the Internet, of course). Dr. Kilmer’s visage continues to oversee the course of treatment from every orange box and the label of every 8 oz. bottle, which also proudly display the names of the fifteen “organic roots in a 10 1/2% alcohol base" of Swamp Root. It sells for $18.50.

For the title of this piece I was going to use the headline from a large ad appearing in The Christian Work over 100 years ago, “How to Find Out If You Need Swamp-Root.” The gist of the answer was simple: “If you are sick or feel badly,” by all means, buy some. What could it hurt?

Today’s sales pitch is much the same. The site which continues to offer it, suggests that customers “Try this herbal tonic today and see how much better you feel tomorrow.” Unfortunately, I couldn’t try it, or even find out what the shipping charges are. A note at the bottom of the page reads, “Not Available - This product is not currently in stock.” Dang.