A decade ago I decided to look into the theory that the Lovewells are somehow an offshoot of a family of Lovells who left England in 1635 and settled at Weymouth, Massachusetts. The result was an entry called “Nobody Knows the Lovells I’ve Seen,” which has turned into one of this blog’s most-studied pages.

People have been puzzling over Lovewell genealogy for well over a century now, although Ezra S. Stearns defined the family’s origin quite differently in his 1911 work, Early Generations of the Founders of Dunstable: Thirty Families. In his mind the Lovells had nothing to do with the Lovewells. Stearns believed that any confusion over the family’s lineage stemmed from the fact that there were two men in Boston named “John Lowell,” one a cooper, the other a tanner.

John Lowell, the tanner, is the ancestor of the Lovewell family of Dunstable. The date of his arrival in Boston is not definitely known. He was there in 1657, and January 24, 1658, he married in Scituate, Elizabeth Sylvester, born January 23, 1644, daughter of Richard and Naomi (Torrey) Sylvester of Scituate. The record of the publishment and of the marriage is at Scituate : ‘These are to Certyfy all those to Whom It may Consceirne that John Lowwell and Elizabeth Silvester hath Been Lawfully Published accordinge to law three Lecture Dayes.’

Flying in the face of Stearns’ confidence, a few twentieth-century Lovewell researchers insisted on taking a different tack, tracing the Lovewells back to one Robert Lovell, who arrived in America with his family aboard the Marygould in 1635.

In order to splice the families together, it was necessary for Robert’s son John to first marry a girl named Jane Hatch. After producing a few children, or at least a firstborn son named John, she had to die, leaving John Lovell free to marry Elizabeth Sylvester and quickly sire another son named John (shades of my brother Darryl, and my other brother Darryl).

Usually the spouses are presented in reverse order, theoretical wife-number-one, Jane Hatch, being trotted out later as an afterthought, accompanied by a note cautioning future researchers about confusing the two young Johns, the first having been born to Jane and the second to Elizabeth. In case you’re wondering, both boys thrived, married and begat offspring.

According to separate family histories, the John who married Elizabeth Sylvester begat Lovewell children and moved to Dunstable, while the one who married Jane Hatch produced little Lovells and moved to Barnstable, a hundred miles in the opposite direction. It also appears that the wife who supposedly died young, Jane (Hatch) Lovell, actually outlived Elizabeth (Sylvester) Lovewell. So much for the two-wives hypothesis. Well, there were two wives, but they were married to different husbands, one a Lovell and the other a Lovewell.

I’ve wanted to blame genealogical sleuth Sherman Lee Pompey (The Wolf and Little Wolf) for leading hardworking family historian Gloria G. Lovewell down this bizarre path in her magnum opus The Lovewell Family (His book on the Lovells/Lovewells came out a decade before hers). However, it’s apparent that the real culprit has to be lurking in a much earlier generation of Lovewells.

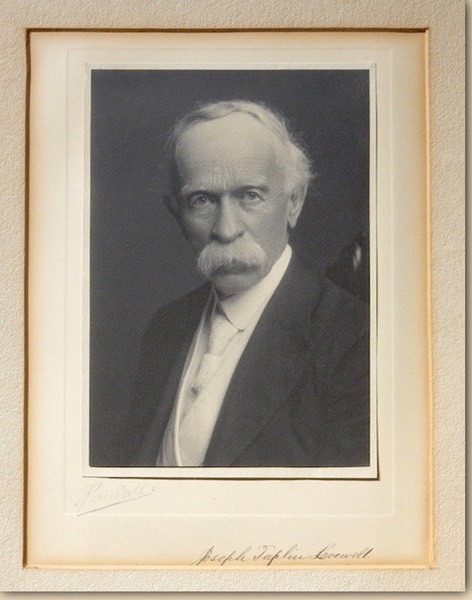

When Professor Joseph Taplin Lovewell filled out his application for Sons of the American Revolution in 1896, he traced his bloodline back to “Robert and Elizabeth Lovewell.” In their 1924 Biographical Genealogy of the Lovell Family in England and America, May Lovell Rhodes and her husband T. D. Rhodes say the 35-year-old wife who accompanied her husband Robert Lovell to the New World was named Elizabeth, although they seem to be ignorant of any connection with the Lovewells, perhaps because there wasn’t any.

The Lovell name carried more than a whiff of old-world aristocracy. The arrival of Robert Lovell and his family at Massachusetts was a comparatively auspicious event, enshrined in “The Original List of Persons of Quality 1600-1700 who went from Great Britain to the American plantations…” In other words, Robert Lovell joined the tide of noblemen fleeing the pro-Catholic rule of Charles I.

Ezra Stearns obviously pegged “John Lowell, the cooper” as a similar person of quality, being a grandson of Percival Lowell (or Lowle) a wealthy merchant who joined the exodus from England.

On the other hand, the first Lovewell in America apparently arrived without fanfare or explanation. He also seemed to omit an “e” from his surname, turning the middle section into a confusing succession of cursive loops. Some transcribers, but not all, rendered the name as “Lowwell." In at least one marriage document and the record of his service in King Philip’s War, the name has been deciphered as “Lovwell.”

As I discovered almost ten years ago, the war record is especially helpful because the regimental documents contain all three names* at the epicenter of this genealogical dustup: “John Lowell,” “John Lovell,” and “John Lovwell,” the latter being involved in the Narragansett Swamp Fight, also known as the Great Swamp Massacre.

Perhaps learning a lesson from the confusion surrounding their ancestor, “Lovwell” descendants would take care to break the name into two discrete syllables with the addition of a crucial vowel.

*As if to make matters more complicated, I’m afraid a “Samuell Lovewell” is also listed. Perhaps John had a brother with better penmanship.