Looking back through the archives I discovered that it was five years ago when I first read the ode composed by Will Jenkins for the 1878 pamphlet of Jewell County history published by Winsor and Scarbrough (see The Unabashed Abolitionist). Writing in 1881 Jenkins noted the key role Thomas Lovewell played in the settlement of the county immediately east of his own, and mused that the hardy pioneer might even be related to that Lovewell of old, Captain John Lovewell, who drew his last breath at the start of Lovewell’s Fight.

For the record, the men were related. Captain John Lovewell was Thomas Lovewell’s great-great-grandfather.

A few days ago I began to be nagged by the memory of an old story I had once seen about the former editor of the Smith County Pioneer going into banking and taking his own life in the face of financial ruin. Unfortunately, I used “Jenkins” as one of the search terms and fished for hours without getting a nibble. As soon as I eliminated the editor’s name from the query involving banking, suicide, Smith County, and Pioneer - bingo.

The man I was thinking of was of course James Beacom, who had succeeded Will Jenkins as “proprietor and editor” of the paper at Smith Center after Jenkins moved to Washington Territory, where he later became secretary of state. The result of my search was the previous installment of the blog, Killed by His Own Bank.

Apparently I hadn’t given the story my full attention when I first saw it five years ago because it appeared in the same newspaper column with a much juicier one, the arrest of James Manning and John Paugh for cattle theft. After returning from a stretch in Leavenworth, Manning would surreptitiously wed Thomas Lovewell’s youngest daughter, the underage Diantha, and then proceed to assault Jake Stofer with a brick on the streets of Lovewell, the result of a grudge years in the making.

This combination of stories appearing together in one neat column seemed to validate two ideas that I couldn’t shake off after weeks spent scanning a slew of old newspapers: First, that the uncertain economic climate of the 1890’s led to a number of suicides, and second, that Thomas Lovewell’s daughters tended to hook up with rascals.

The Courtland Express, published in Courtland, Kansas, showed a steady increase in coverage of suicides following the Panic of 1893. Five were reported on the cover of the paper for September 11, 1896, none of these involving local residents. The fact that many of the deaths were attributed to economic concerns is underlined by the paper’s headline, “Another Banker Suicides,” in the January 8, 1897 edition. This turned out to be the peak year for such coverage with 48 mentions of self-slaughter in all. Thankfully, the number of such reports would see a sharp decline by 1898.

As for the young bachelors who snapped up the Lovewell girls, only Ben Stofer, who married Mary Lovewell, would get off scot free - that is, he was never convicted of a crime nor run out of town.

Although Julany’s husband Edward McCaul was also never convicted on any of the numerous counts of illegal sale of alcohol filed against him, he did run up so many legal bills that he fled Kansas for California in 1883.

T. C. Smith, the young railroad freight agent who had married Adaline Lovewell was nabbed in Kansas City in 1895 after embezzling $1,000 and using the money to indulge in a frantic spree involving all of the deadly sins he could recall off the top of his head.

While James Manning did not become a fugitive from justice until 1899, after marrying Diantha Desdimona Lovewell and assaulting Jake Stofer, his original prison sentence was earned for rustling cattle in 1894.

James Manning and John Paugh of Sinclair township plead guilty to the charge of stealing cattle and were sentenced by Judge Heren to eighteen months in the penitentiary. Stoffer was acquitted of the charge, there being no evidence against him except the assertions of Manning and Paugh, but as this was not corroborated by circumstances the Jury found him not guilty.

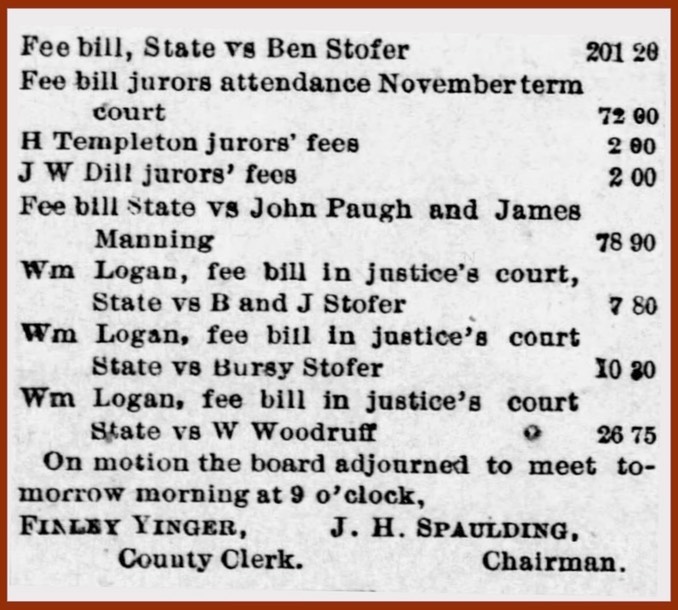

Apparently it was three Stofer brothers, Ben, Jake, and Bursy, who appeared in Police Judge James William Logan’s court at Lovewell, though Manning and Paugh may have singled out Ben alone as an accomplice, or perhaps even the mastermind behind their theft of John Robinson’s cattle.

The clipping on the right coincidentally mentions fees incurred in another matter of larceny in the Lovewell area that year, the case of Willard Woodruff, an Army veteran and pioneer settler who was old enough to know better.

Woodruff had served in the 2nd Kansas Volunteer Cavalry from 1861 to 1865. After marrying Lizzie Clark at Fort Riley in 1866 he may have waited cautiously for Indian attacks to subside before moving his family to White Rock in 1870. Willard appears with Thomas Lovewell as a fellow guest from White Rock in the 1885 photograph taken at the Republic G.A.R. Post. I believe he’s one of the figures flanking Thomas Lovewell and his brother-in-law Daniel Davis, but I’m not sure which one.

A victim of consecutive crop failures, Willard Woodruff had suffered losses on his farm while also losing his savings in the 1893 Courtland bank failure. To make ends meet he had resorted lately to embezzling from the school district where he was treasurer, converting about $500 of school funds to his own use. After appearing before Judge Logan, Willard left town for parts unknown, leaving his wife and two adult sons to shift for themselves during the storm of lawsuits and forfeitures that followed.

It’s not known whether Willard Woodruff was related to Allen Woodruff, another native of New York State who was more than a decade older than Willard and seemed to arrive at White Rock a few years sooner than the younger man. What we do know for sure about Willard Woodruff after his flight from justice in 1895, is that he began receiving veterans benefits in 1909 and died at Kansas City in 1916. Lizzie had preceded him in death in 1911. I’ve seen no evidence to indicate that the two ever saw each other after 1895.