Very few cases have excited more comment, or created more interest than the one I am about to give to the public for the first time. Brief mentions of it have been made in the public prints, on several occasions, but most of them of too “brief” a nature to be valuable. Frontier people are often unjustly censured for their summary mode of dispensing justice, but it is invariably by persons who never make allowance for the almost impossible means at their command of using legal remedies to punish violators of the law.

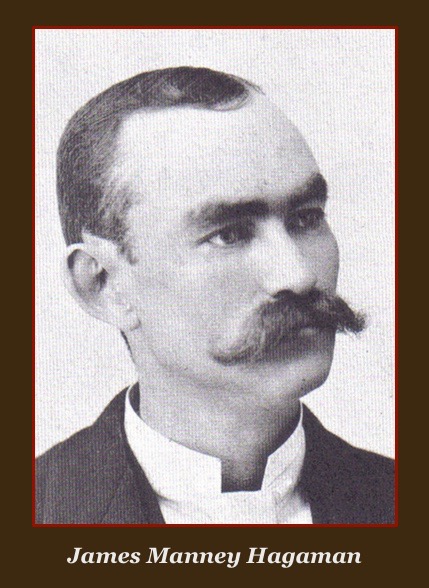

With this preamble, published in the Concordia Blade in October of 1886, James Manney Hagaman broke his silence about the summary justice which had followed the shooting of Ark Bump and Vinson Davis in Cloud County, Kansas, on the afternoon of July 25, 1867.

Hagaman hadn’t been completely silent about the affair, publishing a detailed description of the shooting and the capture of two suspects, described as “German Jew” peddlers from Leavenworth who may have mistaken Bump and Davis for business rivals. However, what Hagaman had presented only sketchily in the pages of the Blade Annual in 1884 was an account of the preliminary hearing which was held before the suspects were led into a field after dark and hanged. He also had little to say about the lynching itself in 1884.

1886 was an election year, tempers were high, memories must have been stoked, and tongues wagged. On September 17 Hagaman’s paper responded to an item from a rival, the Jamestown Cloud County Kansan, which proposed a tell-all biography of the Blade editor. Another editor had previously told the editor at Jamestown to "keep his shirt on,” over some political disagreement. Informed that the paper was helmed by a woman, and thus should have been told to "keep her chemise on,” the Blade began referring to the editor at the Kansan as the "Jimtown Chemise."

THE JIMTOWN “CHEMISE"

"The main biography, (Hagaman’s) will contain a full account of the, 1. Shooting of a peddler. 2. Stealing his pack. 3. Bought off by his father’s murderer, and a number of other interesting enterprises."

-Kansan

The chemise editor of the Kansan has doubtless had some experience in “ringing the bell,” but don’t know how or where in the devil the “clapper hangs.” She has heard something about “peddlers” and “killing,” but has got the matter slightly mixed. She probably refers to the hanging of the two peddlers who shot Bump and Davis, and who was tried, convicted, and some say, “executed,” by the editor-in-chief of the Blade.

Responding to this challenge from “Jimtown,” Hagaman must have decided that the time had come to spill the whole pot of beans. If his enemies were conducting a whispering campaign about his past, why not put his version of events out front? James Hagaman may not have served as judge, jury and executioner in the case, even if he had to admit that it had been largely a family affair. He prosecuted the peddlers while his brother Nicholas defended them, and their father, Justice of the Peace Joseph N. Hagaman, presided over the hearing.

The part about stealing a peddler’s pack probably referred to how Nicholas Hagaman’s fee was paid. After Richard Kennup and Edward Zacharias had been dangled from a tree and buried, their worldly goods were appraised at $500. This amount was returned to a man from Leavenworth who presented evidence of ownership, minus the $150 which was handed to Nicholas, a man with no legal expertise, for mounting what turned out to be an inconsequential defense. James Hagaman never confessed to being a member of the necktie party who dragged the defendants from Sheriff Quincy Honey’s house in the dead of night, but he was privy to a wealth of details learned from two men who were present at the lynching, and Hagaman was all about details. From his account we learn the location of the hanging tree and its species, as well as the diameter of the trunk and in which direction that trunk was bent.

The story was dished out across four consecutive issues of the Blade, but was also consolidated into a pamphlet which the Blade offered for the modest price of fifteen cents. Most of this information and much more, including a summary of witness testimony and cross-examination, is contained in Rhoda Lovewell’s new book, “The Lovewell Family Revisited.” It may cost more than fifteen cents, but, considering everything else packed inside, the cost per word must be far less than what the Blade charged in 1886.

Hagaman’s full disclosure lay snugly tucked away in the archives of the Blade and Blade-Empire until 1980, when it was resurrected by retired Concordia attorney Clarence Paulsen for his column of “Trivial History of Concordia and Environs.” The matter was of more than trivial historical interest for researcher Rhoda Lovewell, who found Paulsen’s collected columns preserved at the Cloud County Historical Museum: Vinson Perry Davis was her great-grandfather, and records of the hearing contain the deposition of the man who lay wounded with birdshot in his chest, while ten witnesses trouped into a makeshift courtroom to testify. One of those witnesses was Rhoda’s grandmother, Orel Jane Lovewell, whose testimony, unfortunately, does not appear in Hagaman’s summary.

Some surprising information does appear, including a familiar roster of White Rock pioneers who were either ear-witnesses to the shooting or were suspected for a time of committing the deed. The testimony of John Marling, then a resident of Marshall County, yet, for some reason, part of the widely-spaced convoy of wagons headed toward Clyde or Clifton, placed the shooters in front of the victims’ wagon. His testimony may have let Samuel Fisher and his son James off the hook. Why the Fishers were once considered suspects is not known, but the idea that Ark Bump was slain by a neighbor has long remained a part of Bump family history. As the story goes, when Ark Bump, who was relatively well-off, refused to lend money to a fellow settler, the man waylaid, shot and robbed him, confident that the attack would be blamed on Indians.

The shooting of Ark Bump and Vinson Davis was blamed on Indians at first, then on Fisher and his son, and finally on Richard Kennup and Edward Zacharias, two peddlers who were apprehended in Washington County one day after the ambush. We can only hope that local sleuths in Cloud County zeroed in on the guilty party on the third try, because Kennup and Zacharias are the ones who were forced to answer for the crime.

The tree they were hanged from, by the way, was a willow.