Born at Irving, Kansas, in December 1878, Nellie Gail was not quite six months old when one of a pair of historic twisters blew the family’s house apart, swept little Nellie into the air, and heaved her nearly a tenth of a mile down the road. A testament to the durability of babies, Nellie landed unhurt to live a long and storied life, even if the story had nothing at all to do with a girl named Dorothy or a man behind a curtain.

The Gail family had breezed through Iowa and Illinois by the time they landed at Irving, where they seem to have stayed for about seven years. John Gail had been only 16 when he enlisted in the Union Army in January 1865. His eight months with the 153rd Illinois Infantry entitled him to join Sackett Post 126 of the G.A.R. at Irving, where he served as Junior Vice-Commander in 1885. The fact that his name does not appear on surviving records for the following year, suggests that the family had moved on by then, probably to Thayer County, Nebraska, where John’s wife Prudence died in 1894 at the age of 40. Remarriage later in the decade to Minerva May Raymond, who was only three years older than his eldest daughter, would yield John Gail four sons, Dewey, Perry, Cyril, and Raymond.

During the family’s time in Nebraska, Alta Gail, who had been flung by the Irving tornado nearly as far as her baby sister, married and moved to Redlands, California. When Alta was diagnosed with consumption, her father headed west with youngest daughter Carrie in tow, to be close to the ailing Alta. Nellie took a teaching job near Seattle, and used her vacations to drop in on her sisters and their father at his general store, the El Toro Mercantile.

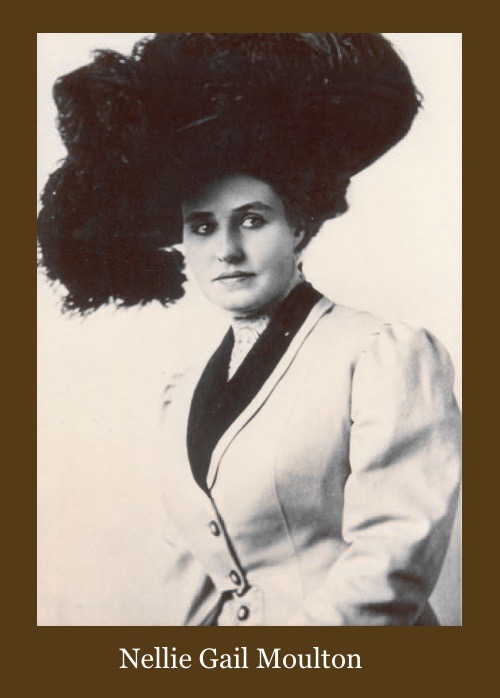

On one of those visits she was introduced to a wealthy, recently-divorced rancher named Lewis Moulton, who was older than Nellie by almost a quarter of a century. After a long courtship the two married in 1908. Besides helping her husband run the 22,000-acre ranch and rearing their two daughters, Charlotte and Louise, Nellie Moulton took up painting, blossoming into an excellent landscape artist, and becoming a patron of the local art colony and playhouse. Although Lewis lived to be 84, the difference in their ages meant a long stretch of affluent widowhood for Nellie Gail Moulton, lasting from 1938 to 1972.

While Nellie and her married daughters finally sold their ample acreage to developers in the 1960’s, there is still a community known as Nellie Gail Ranch in Orange County, as well as a Nellie Gail Equestrian Center. Even the names of Nellie’s girls remain enshrined in Avenida De La Carlota and Calle De La Louisa in Laguna Hills, while the story of Lewis and Nellie Gail Moulton is frequently dusted off for retelling in Orange County newspapers. Besides that fetching picture of Nellie in her feathered hat, one which is passed around rather freely on the web, one or two sites display photos of her with her daughters and offer views of a selection of her paintings.

What is never mentioned in any of the articles, however, is the tale of Nellie’s tussle with a tornado in Irving, Kansas. Although she was a baby at the time and would have no first-hand memory of it, surely her father regaled customers with the fantastic story from behind the counter of the El Toro Mercantile.

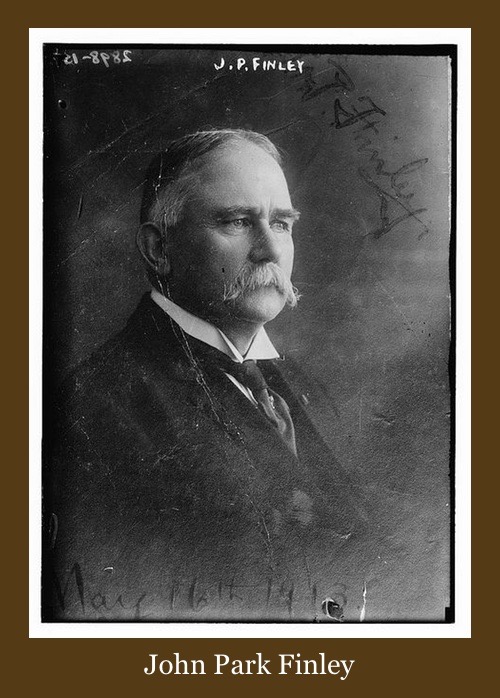

Perhaps I’m wrong, and there were two families with similar names living in Irving in 1879, each with a baby and another small child. Besides John and Prudence Gail and their two girls, there might have been the "Gales” from John P. Finley’s meteorological report, a family who must have clambered out of the mud on the afternoon of May 30 after miraculously escaping death or serious injury, and then vanished without a trace. What seems more likely is that Finley simply spelled the family’s name phonetically when he jotted down notes during interviews (he also spells the name “Shipp” as “Ship”).

There are some genuinely newsworthy stories concerning the Irving tornadoes - among them, the remarkable fact that two powerful funnels from separate storm systems struck the little town, one after the other, less than two hours apart.

An investigator dispatched to survey the dismal scene at the behest of what would become the United States Army Signal Corps, John P. Finley, began making the first extensive study of tornadoes on the Plains. Today he is hailed as the father of severe storms forecasting.

Then, from the human interest angle, there’s that baby girl who survived being plucked into the air and flung approximately the same distance a golf pro can propel a ball with a 7 iron, the baby who would grow up to become a well-known California rancher, artist, and philanthropist.

Instead of any of these, the fun fact we’re generally treated to concerning the Irving tornadoes, is some nonsense about the genesis of “The Wizard of Oz,” a gruesome but beloved anecdote with no apparent basis in reality, and one which I’m afraid I’ve been guilty of repeating, because it’s so darned compelling. Another reason the Oz tale remains popular may be that it’s virtually impossible to disprove. Try googling “Irving tornado” plus “Gale” and you’ll always get something. Even back in 1879, newspaper writers were avid collectors of synonyms, and dreaded using any one twice in the same paragraph. So the storm at Irving is always referred to as a cyclone, a tornado, a twister, a funnel, and a gale. Oddly enough, several papers also spelled the latter word “gail."

Speaking of misspellings - what was it about an email from Keith Jones of Marshall County that led me to recall the many variations of “Lipizzaner” noted in my last posting? Keith didn’t make a big deal about it, but I noticed that he kept referring to a local early-20th-century historian named Emma E. Forter. That’s not what I’ve been calling her. I double-checked my copy of “History of Marshall County,” where the author is listed as Emma E. Porter. Of course, it’s a text-only version which I downloaded from the Internet several years ago, and I now remember puzzling over an updated version of the work, published in 1917, a decade after the original volume came off the presses, credited to one Emma E. Foster. I even speculated at the time that the author must have been divorced or widowed between editions, remarrying someone named Foster.

No, the solution is much simpler. Optical character recognition engines apparently don’t recognize “Forter” as a legitimate word, and substitute either “Porter” or “Foster.” Our misspellings sometimes occur because we don’t know any better, or because our fingers don’t precisely echo our thoughts. Now, there’s a new category of mistakes that happen because our machines haven’t figured out that the spelling of proper names operates by no known rules. Good luck fixing that one.