After bad-mouthing optical character recognition algorithms only yesterday, it was somehow fitting that I should have to spend an evening looking at the world as those poor algorithms see it - so many letters shaped alike, nearly indistinguishable from one another, words spelled according to no known rules, lines jammed side-by-side for no obvious reason.

There’s a selection of wills and probate files waiting to be searched on Ancestry.com, including several from Lovewell ancestors, especially those that didn’t run off to find their fortune and whoop it up along the frontier. There’s a beautifully penned testament from Moody Bedel Lovewell’s sister Betsey Lovewell, who lived in Corinth, Vermont. In 1854, aware of the possibility of sudden death, she bequeathed tokens of affection to beloved brothers and nieces, leaving the bulk of her earthly treasures to her cousin Hartwell Lovewell, a man I take to be the son of Jonathan Lovewell and Sophia Taplin (others may know better). The biggest plum for cousin Hartwell was surely not all the bedding she left him, but the promissory note held against him for $750. That money would be his free and clear now.

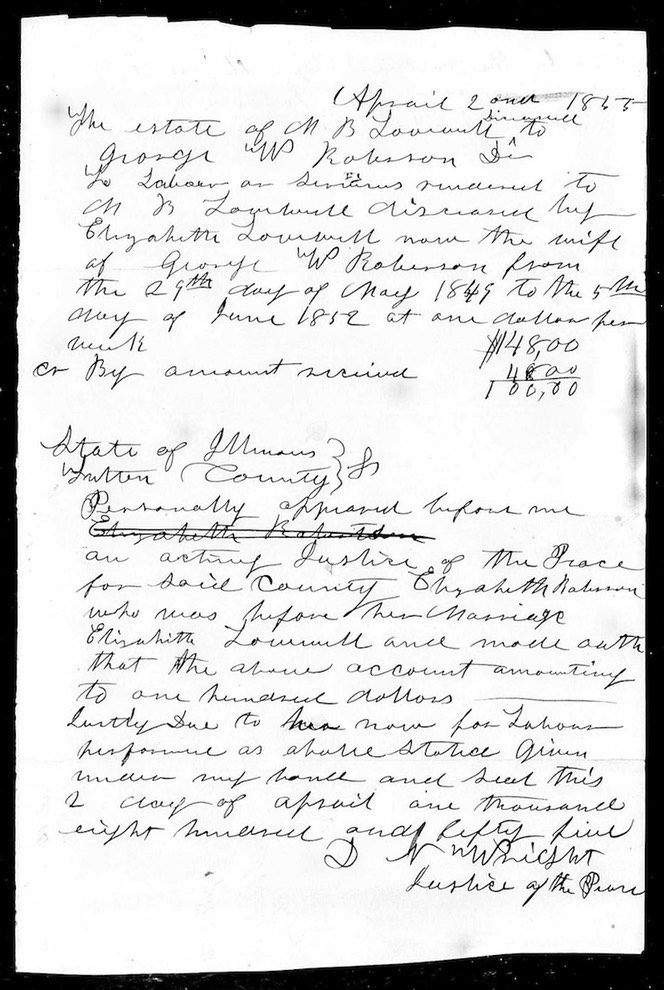

The probate records of both Betsey and Moody Bedel Lovewell remind us that monetary transactions in this era depended on faith, credit, and many scribbled bits of paper. Moody left behind unpaid accounts amounting to more than $30 at local stores for codfish, pickled pork, cheese, soap, tobacco, matches, and other necessities. Calico, batting, muslin, thread and buttons itemized on one list may represent purchases by his daughter Elizabeth, who spent three years looking after her father, and in 1855 hoped to be reimbursed by his estate for the $100 she was still owed for her labors.

Much of Moody’s debt would be covered by the $100 note he held against a local family, on which they still owed $86.50. Added to the various tools, knives, trunks and boxes Moody B. Lovewell left behind, the remaining balance on the note brought the value of his personal effects to $100.20. Moody had been living recently on some land he owned in Livingston County, and he left a promissory note to John Robinson, probably his daughter Hepsabeth’s husband and the man who would be appointed to administer his estate, as payment for taking care of him for a month, hauling him back home to Fulton County to die, and seeing to his burial.

Moody wrote his final promissory note on June 26th and died September 3, 1853. Because of an auction held four years later at the courthouse in Lewiston, the seat of Fulton County, we learn that he had lived for a brief time northwest of Pontiac, Illinois, on land granted to him in 1852 for his service in the War of 1812. Getting some good out of it during his lifetime must have been on Moody’s bucket list.

The claim of Moody's daughter Elizabeth against his estate was handled by acting Justice of the Peace Daniel N. Wright, whose spelling and penmanship had me rummaging for my reading glasses. My wife assures me that the document was somewhat more legible on her iPhone, where she could concentrate on the shapes of words rather than individual letters. I see her point, but it’s still one of those documents where you almost have to know what it was supposed to say, before you can decipher what it actually says.

April 2nd 1855

The estate of M. B. Lovewell deceased to George W. Robinson, due to labors and services rendered to M. B. Lovewell deceased by Elizabeth Lovewell now the wife of George W. Robinson from the 29th day of May 1849 to the 5th day of June 1852 at one dollar per week

$148.00

48.00

or by amount received _____

100.00

State of Illinois

Fulton County

Personally appeared before me an acting Justice of the Peace for said county Elizabeth Robinson who was before their marriage Elizabeth Lovewell and made oath that the above account amounting to one hundred dollars justly due to her now for labors performed as above stated given under my hand and seal this 2 day of April one thousand eight hundred and fifty five.

D W Wright

Justice of the Peace

Anyway, that’s the gist of it, more or less. I’ve tried to give Daniel Wright the benefit of any doubts (I hope others do the same for me), being willing, for example, to overlook his apparent insistence that there’s an “i” in “deceased.” There are probably stories to be culled from such documents, or at least the cogs and gears of family relationships. For instance, there’s the little detail that, ten days after retiring from being her father’s caretaker, Elizabeth Lovewell started looking after another man for free - her new husband.