Reporting Army casualties after the Battle of the Washita in 1868, Ohio newspapers carried the grim report on one of the state’s favorite sons: “Of the officers, Bvt. Lieut. Col. Albert Barnitz, Captain Seventh Cavalry, is seriously if not mortally wounded.”

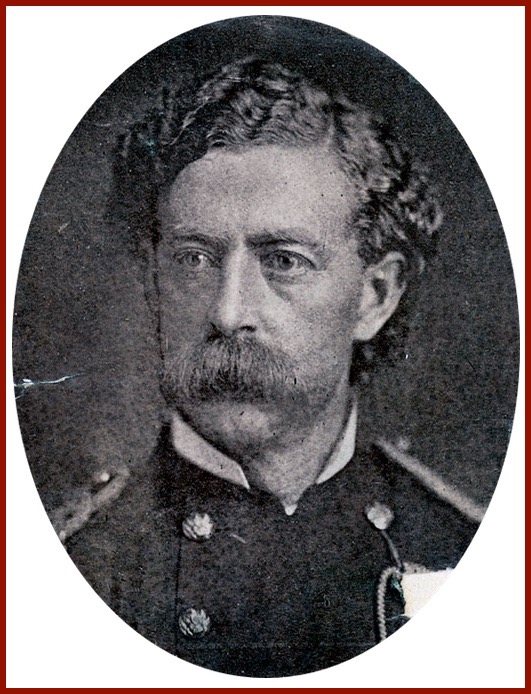

Albert Trorillo Siders Barnitz was a local matinee idol before the war and produced a volume of poetry that had been well received. Fans whose hearts still fluttered at the memory of the handsome, Byronic figure who seized an audience’s attention merely by striding onstage, must have hoped that the papers were again mistaken about Barnitz, as they had been in June 1863, when the Cleveland Morning Leader was forced to print a retraction.

Captain Barnitz Not Dead

The Cincinnati Gazette of Friday morning conains a communication from Mack R. Barnitz, brother of Captain Albert T. S. Barnitz, denying the statement that the latter was dead. Captain B. was badly injured by a kick from a horse, but will recover.

This amended version of events was also wrong, but less disastrously so. Barnitz had been leading a raid in Tennessee when his horse slipped and fell on him, resulting in a broken jaw among other injuries. In June 1864 he again made news when he was shot in the right leg at Ashland Station, Virginia, a wound which left him unable to return to his regiment until autumn. Once more, first reports supposed the injury to be much worse than it really was, and an old friend who wrote for the Cincinnati Commercial, updated the obituary he had prepared for Barnitz a year earlier when first misinformed about his death. The obituary had to go back into the morgue at the Commercial, only to be dusted off again four years later following Custer’s controversial victory at the Washita.

This time the news about Albert Barnitz had not been exaggerated. A physician told Barnitz, who was shot in the abdomen and lay writhing in agony, that the wound was mortal and his suffering would soon end. Custer leaned over and solemnly whispered to the faithful captain that he would receive all the honors due him. Barnitz asked friends to report his death to his wife and tell her not to mourn, but to remember that he loved her.

The wound did, in fact, prove fatal for Barnitz - but not until 35 years later. A few days after the batte, surprised to find the soldier still clinging to life, surgeons traveling with the column cut out a piece of protruding stomach tissue which reminded Barnitz of a length of sausage, and he was soon on his feet.

The word went forward, as usual, that I was dead again, and so my old friend, Murat Halstead of the Cincinnati Commercial, wrote up my obituary in good style and for the third time recounting how I had written poetry in my youth, and had corresponded for his paper during the war, and how I had distinguished myself as poet, journalist and warrior. He may have even shed a tear or two as a parting tribute.

A few weeks later I surprised him by calling upon him to pay my respects as I passed through Cincinnati on leave of absence. I thought he appeared a little disgusted to be again confronted by the apparition of one whom he had so often glorified as dead! At all events, he said, at parting: “Barnitz, the next time you are killed I am just going to say, ‘Barnitz is dead.’ I am tired of writing obituaries of you— and all to no purpose."

When he told the story to a reporter in California in 1890, the irony was not lost on Barnitz that both Custer and the doctor who had pronounced him a goner, were by then long gone. He also outlived his friend Murat Halstead, who had prepared his obituary three times. After his death in 1913 an autopsy found that a piece of Barnitz’s uniform had been dragged into the wound he received in 1868, which became reinfected and contributed to his death at the age of 77.

I first encountered the story of Albert Barnitz and the premature announcements of his demise in “Scalp Dances,” one of the books I consulted for information on the Plains Indian War when I was researching the life of Thomas Lovewell. I was reminded of it lately while scanning through Rhoda Lovewell’s update of the Lovewell family saga, which dedicates several pages to her nephew Dave Lovewell, a frequent contributor to this site.

From 1966 to 1967 Dave served in Vietnam with the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Marines until he was shipped stateside with a severe wound to the back of his skull. At a reunion many years later one of his old Marine buddies was surprised to see Dave mingling with the other guests, having believed for decades that his comrade had been fatally shot. The fatality turned out to be a different soldier, one who had suffered a massive head injury around the same time.

Two years ago, after I hadn’t heard from Dave for a while, his wife Donna emailed me to say that he had been life-flighted to a hospital in Lincoln, Nebraska. The pickup he was driving had crashed head-on into another pickup on a county road near Superior. Dave was bleeding from his spleen and one kidney, his lower back was fractured in three places, and he had suffered numerous cuts and bruises. After doctors repaired him he had to get around in a wheelchair for a time, but seemed fully ambulatory the following spring, when I saw him at the Lovewell/Davis reunion at Lovewell State Park.

He is also the veteran of a few non-life-threatening run-ins with the Nuckolls County Nuclear Waste & Hazardous Waste Monitoring Committee, which had him arrested for obstructing a peace officer when he resisted being removed from a public meeting in 1989. Dave had complained that the committee's public address system was malfunctioning, turning what was supposed to be an open meeting into a pantomime, with a crowd of interested citizens struggling to hear what was being said on stage. Dave shrugged off the men who had taken hold of him, sat in the bleachers for the remainder of the meeting, and was served with a warrant the next evening. Deputies were ready to put cuffs on him until he produced a $50 bond. Dave demanded a trial by jury which found him not guilty.

He is currently in the middle of another battle, fighting a serious health issue. He’s had some setbacks lately, but he takes them in stride and keeps plugging away with determination and hope. Given his past, why wouldn’t he? If, as he seems to be, he’s our modern-day Barnitz, he must have at least a spare life or two stashed in his pocket.