The moment I saw Thomas Lovewell’s letter informing Governor Crawford of Kansas about the perils of living on White Rock Creek in the late 1860’s, I realized that the farmer from White Rock was a practiced correspondent. Although his appeal for arms covers several pages, the words at the end had been formed as swiftly and surely as those at the start, by a pen that fairly raced across the lined paper.

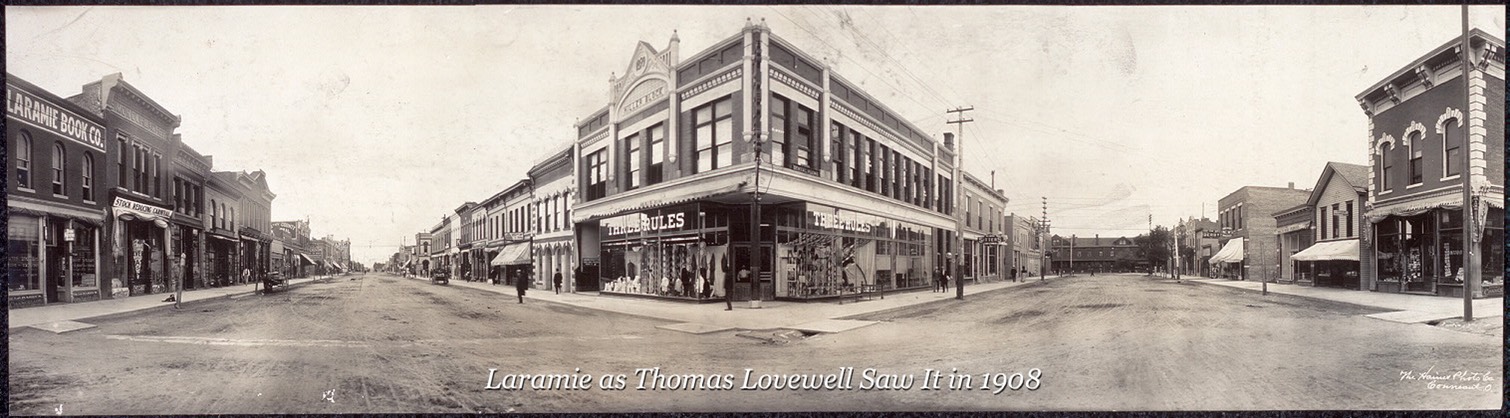

While no further letters have come to light since that first discovery several years ago, copies of two more notes have surfaced, both addressed to newspaper editors. In 1870 he wrote the Lawrence Tribune to set them straight on the exact location of a garrison of soldiers stationed in the Republican River valley. Thirty-eight years later, Mr. Lovewell penned a quick note to the editor of the Laramie Republican and tucked it inside the envelope along with his annual payment. We know about the note, of course, because the editor decided to print it.

Veteran Subscriber Now Capering Colt.

The following note from Thomas Lovewell of Loverwell, Kas., well known in this community, containing remittance for the renewal of his subscription to the weekly edition of the Republican, was received today: “I will say that we have fine weather here. I passed my eighty-first birthday all right and am now chopping and saving wood for next summer’s use. I see that your banks are all right. Good for them. I hope you won’t get snowed under this winter.”

With a text only a few characters longer than the constraints imposed on Tweets (until a few months ago), Thomas briskly covers the local weather, passes along news of a personal milestone, describes how he’s keeping himself occupied, and then offers a cryptic comment on the economic climate before wishing his friends in the mountains a mild winter. It was his query about the banks at Laramie that caught my attention.

The panic of 1893 had spread into a nation-wide economic stagnation that lingered until the end of the century, and would be followed by another major disruption of the money supply in 1914. As Thomas Lovewell’s remark reminds us, in between the two crises came a little case of monetary hiccups that lasted from October through December of 1907. It started with the plight of a cash-strapped central bank in New York City that quickly sent ripples across the country. While only 73 banks would suspend operations that year compared with over 500 in 1893, before the system righted itself, many businesses would find their cash drawers running on empty.

The banking system took a stopgap measure of essentially printing its own money, distributing clearing house loan certificates - bank IOU’s - promising to exchange them for cash as soon as it became available. In some cases certificates even made their way into the hands of individual customers, in denominations as small as one dollar. Mercantiles and mining companies who balked at paying their workers with this money-substitute, probably changed their minds when faced with the alternative of closing up shop for a time. Resorting to loan certificates, suspending or limiting cash withdrawals, and declaring bank holidays in a few states, seemed to tide everyone over until the panic subsided by year’s end, and was quickly forgotten.

In the midst of sending newspaper clippings from Wyoming, Lovewell researcher Phil Thornton also shared a picture of an auction item he was bidding on recently, a memento from Shuler’s General Merchandise dating from the first decade of the 20th century. I’m not sure what’s stamped on the back of this particular coin, but most octagonal tokens of the early 1900’s could be exchanged for 10¢ in merchandise, although I’ve seen one that claimed to be worth 50¢.

Minting their own coins, the nickel-and-dime version of what banks did during the 1907 money crisis, may have seemed a shrewd move for shopkeepers. Trade tokens were more than advertising gimmicks. Merchants could hand them out to customers as change - even though the coins were accepted as legal tender only when they came home to roost.

It should come as no surprise that the heyday of American trade tokens, from the 1870’s to early 1900’s, coincided with the unsettled economic times between the Civil War and World War I. Tokens may have played some small part in keeping local business flowing smoothly whenever the nation’s supply of bona fide cash threatened to dry up.

By the way, L. E. Shuler, the Lovewell merchant responsible for the coin which caught Phil Thornton’s eye recently, must have been Lewis Shuler, the son of Thomas Lovewell’s buddy and White Rock pioneer Thomas Shuler, “that jolly old blacksmith” who had also been chief salesman at Morlan Brothers in the 1870’s. As I reported back in 2013, Phil’s grandmother and White Rock historian Orel Poole once wrote a brief historical sketch about Shuler (see “Casting Call for a Hero”), one which I should track down and share one of these days.

I wonder if those pioneers would be surprised to learn that we still read and write about them a century after their time. I’m sure L. E. Shuler would be amazed to discover that those ten-cent merchandise tokens he passed around to publicize his store are now worth something like 500 times their face value.

Not bad for a chunk of metal that was worth a dime only because Lewis Shuler said it was.