Tom Robinson, a Lovewell alumnus who lives in Texas these days, sent me a picture a while back, curious to know if I recognized any of the subjects as a relative. Tom has the same last name as my grandmother, but seems to be from an unrelated line of Robinsons, and while his great-grandfather lived in Sinclair Township in the 1880’s surrounded by neighbors named Switzer, I’ve been told that none of them were any kin of my own forebears.

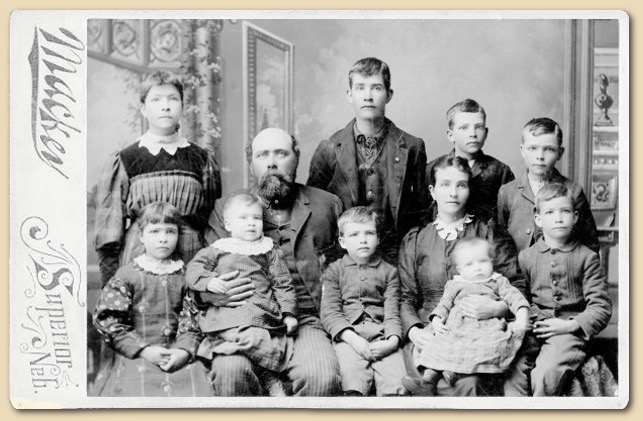

The picture, taken at T . M. Mackey’s Studio in Superior, Nebraska, probably in the 1890’s, reveals a family with nine offspring, whose ages seem to span at least two decades. Tom tells me that his great-grandmother helpfully labeled the subjects of the photo as “neighbors.” Is there any sense in even trying to guess who these people are? Probably not, but that’s never stopped me before.

In an era when photographic portraiture was still fairly rare and reserved for special events, the idea that one farm family was handing out copies to their neighbors struck me as unusual. I once came across a family portrait of persons unknown among my dad’s photo collection, and was stymied as I kept trying to match up their faces with the names of Switzer relatives, until I found a likeness of Professor E. H. McNichols in a Sinclair High School yearbook. With the Great Depression still suffocating family budgets, prints of the McNichols family portrait must have made thrifty presents for graduating seniors at Lovewell. Perhaps it was finding that picture of my dad’s high school prof that made me wonder if the photo in the Robinson family might represent something more than just next-door neighbors who happened to have a gaggle of kids; perhaps someone in the photo played an important role in their lives. For instance, the bald-headed man might have been their minister.

There is an area west of the village of Lovewell that has been known for nearly 150 years as Switzer’s Gap. Many years ago I asked my father if the name had anything to do with our family. He shook his head and said the place was named for a minister named Switzer who had a cabin there. My mind pictured an eccentric Bible-thumping hermit eking out a living in a rustic shack perched on the side of a windswept hill, a character something like John the Baptist as Charlton Heston played him in “The Greatest Story Ever Told.” I discovered later that I was on the right track in one respect. James L. Switzer may not have been a hermit surviving on locusts, but he was a Dunkard.

Born James Lebbius Switzer in Maryland in 1837, the Rev. Switzer would sire at least enough children to populate the family portrait seen above, long before departing this world at the age of 92 in Jasper County, Missouri, only a few miles from where I live now. Since the Dunkards evolved from the Old German Baptist Brethren at Schwarzenau, the Germanic faces staring back at us are what we might expect to see in a verified portrait of the James L. Switzer family.

So is this a picture of that family? There seemed to be sufficient evidence to consider James Switzer as a person of interest, though perhaps no more than that.

I learned a valuable lesson in skepticism a long time ago. In 1967 CBS broadcast “The National Science Test” hosted by Harry Reasoner. Using film clips and photographs, the program asked viewers to choose the best scientific explanation for what they were seeing. For instance, superimposed over news footage of a mighty Saturn rocket beginning its ascent amid churning columns of whte vapor, came the question, was it true or false that the rocket was being lifted off the launch pad by pressure exerted against the ground by the rocket exhaust? This one was false, of course. The rocket was propelled upward by Newton’s Third Law - the ground had nothing to do with it. There was at least one trick question in the show, but one that stuck with me. Shown a picture of distant hills and a cloud bank bathed in a golden glow, streaked with swatches of crimson, Reasoner asked viewers to decide whether it was a picture of a sunrise or a sunset. When the time came to reveal correct answers, it made no difference which one we in the audience had chosen - points were deducted for picking either one. There was simply not enough information given to reach any valid conclusion, except, “I don’t know.”

Feeling the same way about that picture taken over a century ago at a studio in Superior, I nonetheless began to compile a comprehensive list of James Switzer’s children, and tried to collate them with faces in the photo. It wasn’t easy, since we can’t be absolutely sure that none of those young people in the picture are grandchildren, and we don’t know for sure what year the picture was taken. Fortunately, I wasn’t at the task for long when a side-trip to Ancestry let me off the hook.

In the Public Member section I found a portrait of a man with dark, bushy eyebrows, a long flowing goatee, and a dense pompadeur. The subject of the picture, which was taken in 1895, is identified as James Lebbius Switzer. Except for radiating pastoral warmth rather than wild-eyed zealotry, he looks exactly as I imagined him when my father first explained who he was.

I have no idea who the people in that portrait are.