If it’s not yet widely available, Rhoda Lovewell’s updating of “The Lovewell Family” should reach the market soon, and it’s a staggering testament to diligence, scholarship, and family devotion. Rhoda’s recent phone call began as an alert to let me know, “Here it comes.” I was well warned. I’ve always spoken of Gloria Lovewell’s 1979 publication as the magnum opus of Lovewell literature. Well, it has been dwarfed. While the original still lies embedded within the core of the new volume, it has been expanded in every direction. Weighing in at over a million words, “The Lovewell Family Revisited” may not be a page-turner to be devoured cover-to-cover over the course of a month, but a resource to be mined for decades. Thankfully, it’s fully indexed, and I began picking up new information immediately.

I mentioned to Rhoda that I had finally heard from a descendant of Lyman Lovewell, one of the younger sons of Zaccheus Lovewell, and a man I suspect of being the “L. Lovewell” counted as a head of household at an abolitionist enclave in Marshall County, Kansas Territory, in 1857.

“Do you know about Leonard Lovewell?” she asked. I admitted that I didn’t. I knew of a modern-day Leonard Lovewell, but not one who was alive in the middle of the 19th century. When her book arrived I quickly dived in looking for Leonard. Without divulging too much of what Rhoda has uncovered concerning him, I’ll just say that he was apparently a real character. No one knows for sure exactly how Leonard fits into the family tree, but Rhoda makes a good case for his being the brother no one talked about in the Rev. Lyman Lovewell’s family.

Among the paperwork she uncovered was Leonard’s military record, which was the opposite of distinguished. However, since he did sign that enlistment paper, we know that he was a bit above average height with a ruddy complexion, brown hair and gray eyes. The description would come in handy when the Army needed to track him down. Twice.

With two candidates to consider, which one might have been the “L” who camped along the Black Vermillion in 1857? Because we know that Daniel Davis named his newborn son “Kansas Victory,” we can be sure that the Lovewells and Davises arrived in Marshall County full of abolitionist zeal, and Lyman Lovewell wrote the book, or at least the pamphlet, on the crimson stain of slavery. We know his family kept in touch with Thomas even after Lyman’s death, because Lyman’s son Lucien visited cousin Thomas at White Rock during the summer of 1868, when the Republic County organizational census was being taken.

On the other hand, Leonard Lovewell has the advantage of proximity. He seemed to follow the trail laid down by Moody Lovewell’s boys, though he also liked to keep his relatives at arm’s length. He lived for a time in northern Warren County, Illinois. When several of Moody Lovewell’s boys moved to Iowa in 1854, Leonard moved there too, albeit to the far eastern side of the state, sometimes along the very banks of the Mississippi, where he liked to stow his supply of hooch. One of Leonard's sons was married in Concordia,Kansas, 30 miles up the tracks from the village of Lovewell.

After arriving from New York State, the Rev. Lyman Lovewell lived most of his adult life in far-off eastern Michigan.

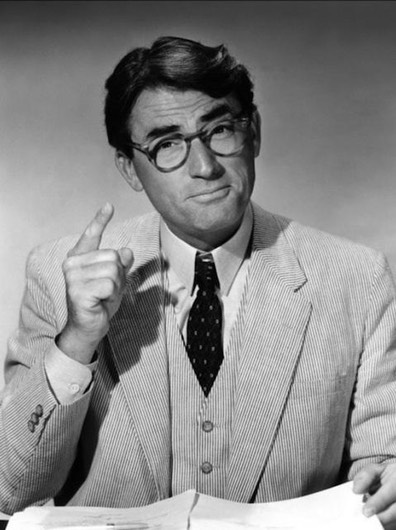

As I sometimes admit, when I think of ancestors and their neighbors, I like to cast the parts with recognizable actors. I used to imagine the figure inhabiting the cabin just up the path from Thomas Lovewell’s place in Marshall County as resembling the resolute and calmly authoritative Gregory Peck (whom Lyman did resemble), playing Atticus Finch. Lyman strikes me as a devout but entirely reasonable man. Who better to play him? Now I have to get used to the idea that the man living there might have better suited the talents of Howard Morris, getting the chance to reprise his role as Ernest T. Bass.

Either candidate had to be separated from his family in order to take part in this righteous crusade in Kansas Territory. Lyman might have made the sacrifice in order to shepherd the little flock of Christian soldiers which he and Horace Greeley had sent into battle to storm the ramparts. But it’s also possible that Leonard could have been on the run again, hiding out where he thought no one would look for him.

It really could go either way.