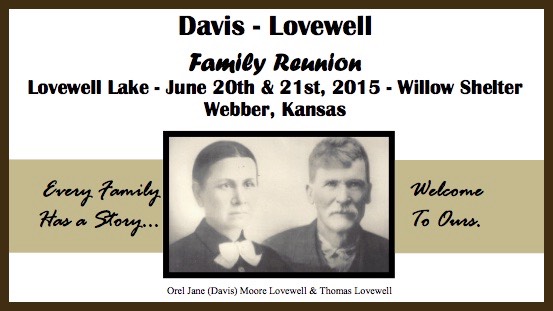

The website reaches its second anniversary at the end of summer. It went online a few months after the family reunion in 2013, and it’s almost time for the gang to assemble once more at Lovewell State Park. Patricia Lange and Carolyn Simms are in charge again this year, so a few days ago Pat sent me a handsome invitation to the event attached to an email. I gazed on it with misgivings, because the centerpiece of Pat’s handiwork turns out to be the same family portrait that was the subject of a blog entry I had posted only a few hours earlier, in which I contend that the woman in the picture has been misidentified. Unfortunate timing makes my latest contribution seem like a shot across the bow, and makes me look like a spoilsport, which unfortunately I sometimes am. I’m hoping that the Lovewell ladies will still feed me when I show up to give a couple of presentations at their event on Father’s Day weekend.

The Jim and Jean Lovewell family will be back to share pictures and memories of their visit to Minster Lovell at Oxfordshire in 2012. A few photos taken by Jim and Jean's son-in-law Rick Berckefeldt continue to grace the slideshow on these pages, even though I also have to share some bad news about the connection between the Lovell and Lovewell families which the pictures of Minster Lovell celebrate. If the Lovewells did indeed branch off from the Lovell family tree, then the split probably occurred before Robert and Elizabeth Lovell sailed from Weymouth aboard the Marygould in 1635. It seems unlikely that any of Robert Lovell’s boys were transformed into Lovewells after all. I still have some pruning to do on this site.

Today’s blog entry is about the 200th I’ve submitted since launching Lovewellhistory.com. Two years and 200 postings may be the endeavor's most obvious milestones, but there’s also a subtle one. By my tabulation I have now written over 208,000 words concerning the Lovewells and their neighbors, as many words as Herman Melville wrote about a certain white whale in “Moby Dick," which is considered a long book. Reaching this word count would have coincided with the release of “In the Heart of the Sea,” a film about the real-life incident that inspired Melville to write his masterpiece, if the studio hadn’t flinched. Instead of splashing into the water during the crowded spring and summer schedule, the Ron Howard film starring Chris Hemsworth will now compete for ticket sales with “Star Wars.” Best of luck with that contest, lads.

While I’m afraid I haven’t churned out a classic over the past two years, a few interesting things have bobbed to the surface now and again. Thanks to Thomas Lovewell’s trip to Topeka in 1902 we’ve become acquainted with his cousin, Prof. Joseph Taplin Lovewell, Joseph's daughters Marguerite and Carolyn, and Marguerite’s descendants. The professor, you might recall, was a friend of Alexander Graham Bell and the great explainer of science to his generation. Marguerite was an operatic soprano with a girlhood dream of performing in the great opera palaces of Europe, but who settled for matrimony and motherhood, along with plum solo assignments in concert halls on the West Coast of the U.S., and several large churches in the Northeast.

One of my favorite mysterious figures from the era of “Bleeding Kansas” is a trapper and fur trader known to history as Julian Changreau (I’ve learned that the family name was originally written “Gingras"), Thomas Lovewell’s neighbor along the Black Vermillion in the 1850’s. Last month I heard from a woman named Peggy who believes that the Frenchman and his Sioux wife were her great-great-great-grandparents. Peggy admits that she has little information to offer about Julian, but more about his son Louis and another of her great-greats named Jean Baptiste "Big Bat" Pourier. Pourier’s command of English, French and Lakota seemed to earn him almost continuous employment as a guide and interpreter during the Plains Indian Wars. He was a friend of Chief Red Cloud, served as a translator during the 1868 Fort Laramie peace negotiations, scouted for General Crook only days after the Battle of Little Big Horn, carried the body of Crazy Horse back to the Oglala Lakota chief's home after his murder, and was present at the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre.

Not only did I learn some enlightening facts about an eyewitness to Plains history, following the trail of “Big Bat” Pourier taught me a few new ways to spell the family name of Peggy’s less famous ancestor. To “Gingras,” “Shangrow," and “Changreau," I can now add “Shangreaux" and “Shangrau.” The last of these may prove the most helpful in pinning down the story of the elusive French-Canadian trapper who lived for a time in Marshall County, since the pronunciation of “Gingras” seems to have been pretty close to “Shangrau.”

While I started this site chiefly to share what I’ve already learned about Lovewell history, it’s also served as a sort of chum line, drawing new contributors to the bait. Many thanks to A. J. Whitney for sharing her postcard view of the town of Lovewell as a quaint country village, Dave Lovewell for his gems of family lore, Phil Thornton for his snapshots of Round Mound and Nelsonville, as well as many gleanings from the National Archives, and to everyone else who’s helped fill in some of the gaps.

History is a giant puzzle, and many hands have formed the mosaic that’s taking shape. Can’t say we’ve snagged the Great White Whale yet, but then neither did Ahab. So we’re at 208,000 words and climbing just past “Moby Dick” (depending on how you count). What’s the next milestone? Well, there’s “War and Peace” at 587,000 words. Lots of battles and some romance in that one, I’m told.