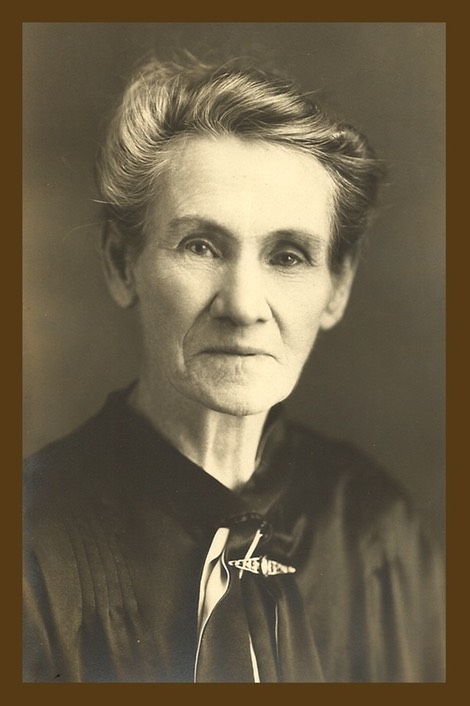

One of the most interesting historical treasures brought to my attention last year was the story of LuNettie Lovewell Lindley, William and Martha Morris Lovewell’s second child, born in Iowa in 1854. What makes the little collection of family tales (originally posted on Ancestry and shared on FamilySearch) so valuable is that they seem to have been dictated by LuNettie herself only a few years before her long life came to an end in 1948.

Her recollections of an indifferent stepmother, a pet lamb, a prized paper ten-cent piece, and the tribulations of poverty, unwanted marriage proposals, toothaches, disease, and death by childbirth, provide a vivid sketch of life in northeast Kansas in the second half of the 19th century. They also contain some valuable family information, though no solid answers to a few nagging questions about LuNettie’s father, William Bedel Lovewell.

Her tale begins in 1851 with a description of her newly-married parents’ move from Illinois to Iowa.

The claim in Ringgold Co. consisted of hilly grassing ground cut thru by Grand River. William being a carpenter constructed a fairly good frame house for his family. He bought cows and sheep. He built a mill on Grand River and ground the grain for the surrounding neighbors. He also used the water power to cut huge blocks from the native wood. These were made into shingles. The country was wild being inhabited with wolves and Indians. Of course, the Indians were mostly civilized. The women picked wild berries and would go from house to house selling them to the white people. They also sold or traded beads. The Indians lived in log cabins with puncheon floors (made of split logs, flat side up).

The first child born to Martha and William was Elizabeth. Auburn haired, blue eyed and quick tempered (The temper was a cause of much grief both to herself and others). Three years later, in 1854, LuNettie (later called Nettie) was born. She had dark brown hair and blue grey eyes. Her disposition was like her mother’s, patient and unselfish and very ambitious. One of the Indian women, seeing the pretty white baby, wanted to trade her papoosie for her. Nettie was joked about this incident as she grew up. Martha had three more children: Mary, Frank and Harriet. With her last a boy, Landford, she died and the baby also.

William worried along with his little brood with the help of the older children for a time. He then married red-haired quick-tempered, Matilda Wise. She was very young and the responsibilities of a large family made her irritable. The children didn’t see much pleasure but were made to help with the work. Young Nettie, always a lover of the out of doors, helped round up the cows and sheep. Also she helped her brother Frank cut and carry the wood for the fireplace. One time as the family was going down to the mill, Nettie exclaimed as it came in sight, “Oh! There’s the damned old mill,” meaning, of course, the old mill dam, as they called it. This was occasion for much laughter.

Nettie Lovewell Lindley's short memoir also covers her adventures as the prototype for a Harvey Girl in Hugo, Colorado, in 1880 (see “Well-Paid Single Women”) and her life in Lawrence with the man she finally married, Will Lindley. It's well worth reading in its entirety, even if you’re not related to her. According to “Vicki1685," who posted the writings and several family photographs on Ancestry, Nettie dictated the story while her blind daughter Estella typed it. I was first inclined to see typos and mistaken homophones in the paragraphs above, “grassing” for “grazing,” “along” for “alone,” and “worried” instead of … well, I couldn’t think of anything close.

No, on second thought, Estella probably wrote exactly what her mother had said. These are, after all, the memories of a 19th century woman, for whom a pasture was still "grassing ground,” and who used “worried” in the sense of “struggled.” The family struggled along without a wife and mother for a while until it was clear that even a harsh young stepmother such as Matilda Wise would be better than none at all.

As for what she didn’t say: Was her father the same William Lovewell who a few years earlier had married Charlotte Bohall and then deserted her and their two little boys in Indiana? Either he wasn’t the same man, or Nettie didn’t know about her father’s earlier marriage, or else she knew enough not to talk about it. Some family researchers continue to refer to Martha Morris Ogden as William Lovewell's first wife. If she was, she was a decidedly atypical choice to be a young frontiersman's first bride. Martha was three or four years older than William, a 32-year-old widow with four young children underfoot when they paired up in Fulton County, Illinois, in 1850.

William and Martha's daughter Nettie proudly mentions that her father had once owned more land than anyone else in Ringgold County, but never drops a hint about where his seed money came from. If the death of Lorenzo Ogden left Martha a widow with property, she might have seemed a much more attractive catch for a 28-year-old man on the rebound from an unhappy first marriage. Of the several parcels of land William and Martha Lovewell acquired in Ringgold County, at least three, totaling nearly 270 acres, were purchased in Martha’s name.

The only problem with the idea that Martha bankrolled her husband’s land-buying spree in Iowa is that his brothers Thomas and Solomon joined him there, and Thomas, at least, accumulated a few hundred acres of his own. I’ve only seen the federal land patents issued to the Lovewell brothers and Martha in 1856, which alone amount to 469 acres, and would have cost them $586.25. These were late purchases at the standard price of $1.25 an acre for federal land, all made in only one year. We also know that Thomas had acquired and sold large tracts of Iowa farm land before then. Where did the money come from? One possibility comes to mind, and, if true, it is as they say in the overblown language of cable TV reality shows, a game-changer.