In 1892 the Kansas Bank Commissioner’s annual report noted that four banks had failed during the year, and suggested tightening a few regulations.

In the case of the Farmers’ Bank, Hope, Kas., W. P. Robinson, cashier, absconded with most of the funds of the bank, and the creditors immediately attached before the commissioner had notice; but as soon as notified he left immediately for Hope and demanded possession of the loans and discounts and other assets of the bank held by attaching creditors. They refusing to yield possession, a receiver was appointed, and a demand made by him, and I am informed that the district court made the attachment good.

Again, in the case of C. T. Ewing’s bank, at Thayer, right on the eve of its failure he transferred many of his loans and discounts, real estate and other property, to various creditors. In both cases the object of the law was defeated, in that the depositors should be paid pro rata of the assets of the insolvent bank.

In other words, the depositors at both Hope and Thayer were out of luck. There was a separate matter that raised red flags for the Commissioner. Some small-town banks with capital stock of only $5,000, held deposits ranging from $40,000 to $75,000. Since the stockholder’s liability was limited to twice the face amount of the stock, “you can but conclude that the liability is entirely too small for the protection of depositors.” Perhaps the minimum should be $15,000. One newspaper which carried the story in its September 1st edition, agreed that “the commissioner scores a good point and wins the approval of all honest bankers and thoughtful business men. We hope the next legislature will put his hint into the statute.”

The Commissioner’s report, printed in Aaron Everest’s hometown paper the Daily Champion less than a year before the failure of two of Everest’s banks, was practically a blueprint for fraud, or at least for under-regulated banking shenanigans. Of course, Everest needed no blueprint, and part of what now seems to have been a deliberate scheme from the start to separate investors from their money, was already in place: Aaron Everest’s banks at Courtland and Jamestown each had been launched with only $5,000 of capital stock.

Like W. P. Robinson at Hope, the cashier of the State Exchange Bank in Courtland fled with the bank's remaining funds, while Everest’s right-hand man at Jamestown, cashier F. P. Kellogg, dashed off a flurry of overdrafts even as the bank was about to go under in the summer of 1893. As for Aaron Everest himself, he made sure that some of the largest creditors who were about to line up with their hands outstretched were persons named Everest. His daughter Kittie Clover claimed she had loaned her father $15,000 and had never been repaid. His son Frank and daughter-in-law Belle insisted they were owed $79,013.

Some of the money drained from depositors’ accounts in Courtland and Jamestown may have been put beyond the reach of creditors by being laundered through government bonds. In March 1894 an ailing Everest purchased ten bonds, bequeathing them to his wife Marie M. Everest, the woman who would very soon be his widow. The bonds could be redeemed at their face value of $1,000 each when they reached maturity in 1904. Unfortunately, Mrs. Everest cashed in her chips in 1903.

The Everests seem to have gone to great lengths to acquire and protect what was, for the Gilded Age, a relatively modest amount of money. Because Marie Everest never properly itemized her husband’s estate, we don’t know for sure what he was worth at his death in 1894, but back in 1882 his wealth was rumored to have been in the neighborhood one million dollars. It’s possible that the real estate bust of the late 1880’s and the depression of the early 90’s took a toll on the railroad lawyer’s fortunes. His rickety small-town banks and their risky mortgages may have been a last-ditch effort to cover his losses.

According to Hallie Farmer’s 1922 thesis “The Recession of the Frontier,” with the frenzy of railroad-building chugging to a halt in 1887, Aaron Everest’s home town of Atchison tried to keep the money-machine humming through local real estate investments.

It began March 13, 1887 when the Atchison Land Investment and Improvement Company, organized by Atchison bankers, paid $1,500,000 for city real estate. At once the fever raged. Before the week was out farm tracts were being bought and turned into town lots. In the second week a real estate exchange was opened with fifty dealers as charter members. The street in front of the exchange was thronged with buyers. Sales were $700,000 for the week. Senator Ingalls was offered $1,000 an acre for a farm which he bought three weeks earlier for $75 an acre but he refused to sell. A lot bought in the first week of the boom for $1,500 sold in the third week for $2,500. An hour later the purchaser refused $3,000 for it.

The Atchison boom lasted four months. Investors who bought in late or held on to their prizes too long took a bath. Aaron Everest may have been among the losers.

The booms in the larger cities were the most spectacular, but the same drama on a smaller scale was being enacted in hundreds of little towns and villages all over Kansas and Nebraska and to some extent in Dakota. At Clifton Kansas (the place cannot be found on the map today)* land which a few years before had been regarded as worthless was selling at $5,000 per quarter section. Near Concordia a village church bought fifteen acres of land for $9,000, platted it and sold it for $20,000 using their profits to build a new church. Many towns which were established in Kansas in this period have disappeared today.

The town of Lovewell in Jewell County got a rude introduction to the “Gay Nineties” when the depot agent at Lovewell Station absconded with $300 in 1890, after the station had been in operation less than two years. At least it was only the railroad’s money, and the culprit was nabbed in Nebraska a few weeks later.

That little news item and the whole Aaron Everest episode got me to wondering why a decade of economic stagnation, ruthless buccaneering and rock-bottom depression ever became known as the “Gay Nineties.” According to Wikipedia the term was invented by an illustrator named Richard V. Culter, the Norman Rockwell of his day, who published a series of drawings presenting the years of his boyhood seen through a romantic haze. The drawings were published the same decade as Hallie Farmer’s thesis, which yanked away the rose-colored glasses.

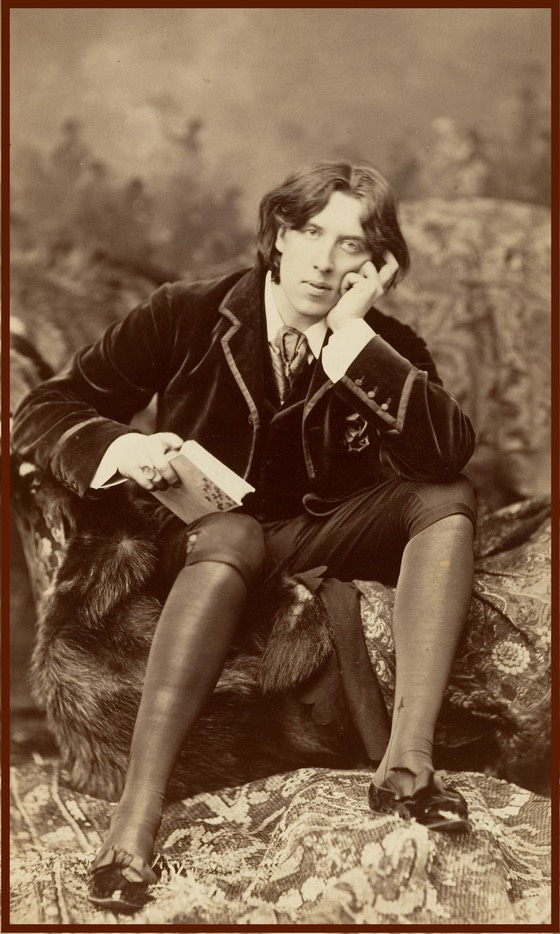

In England the decade is known as the “Naughty Nineties,” largely because of the antics of the likes of Oscar Wilde, pictured above, looking fairly glum, but who was actually gay in the modern sense of the word. The decade was not especially gay in any sense.

* Hallie Farmer’s difficulty in locating Clifton in the 1920’s is understandable, though not related to the town’s diminishment. It was actually more populous in 1922 than it had been in 1887, but lay along the boundary between Washington County and Clay County. It is notoriously hard to find on a map.