A couple of years ago my old friend Chuck Westin from Belleville sent me a folder full of old brochures and newspaper clippings of historical and personal interest. One of these was a photograph of a classroom full of kids from my days as an elementary student in Formoso, Kansas.

I received the same shock almost almost everyone gets sooner or later, when I realized how tiny that room appears in the photo and how diminutive we pupils were. When we’re less than four feet tall our viewpoint can make a modest classroom seem cavernous.

I was reminded of that sensation when I caught myself chuckling over a reminiscence from James Franklin Lovewell about his grandmother, Orel Jane Lovewell, in the pages of The Lovewell Family, a book compiled by his wife Gloria.

My grandmother Lovewell was tall for a woman. She was never overweight, but remained slender all her life. In her later years, she became almost too thin, but her jaw remained square and determined. She always wore long dresses that dragged on the floor, dark in color, with a brightly colored apron, and a dark-colored kerchief on her head, tied under her chin. She had a severe little part, right smack down the middle of her grey hair

Having examined a few photographs of Orel Jane I can vouch for almost every detail of her grandson’s description. Of course, none of the photos are in color but the kerchief on her head is dark, her jaw is square, and her hair is always parted in the middle. However, the only picture I’ve seen of her standing next to someone else who was also standing, casts doubt on the claim that she was “tall for a woman.”

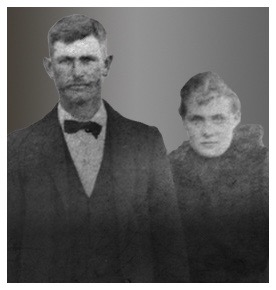

In a photo apparently taken by her daughter Mary (who seemed habitually unable to hold the camera level), Orel Jane is standing next to Mary’s husband Ben, who admittedly was quite tall. For the sake of comparison however, have a look at a picture of Ben and his wife stoically posing side by side at a gathering of mourners on the front porch of the Stofer residence. Mary Julina (Lovewell) Stofer seems to have been taller than the average woman, circa 1900. Orel Jane Lovewell, the crown of whose head in the previous photo doesn’t even reach Ben Stofer's shoulder, appears to have been remarkably petite.

James Franklin Lovewell’s memory of his grandmother as an imposing figure may have less to do with her actual stature than her personality, her slender frame, and her habit of wearing long black skirts with hems that dusted the floor. It also seems likely that the boy’s most vivid memories of his grandmother were from a time when Orel Jane really did appear rather tall from his point of view.

Around the time James was eight or nine years old his family moved to the vicinity of North Platte, Nebraska where his father worked for railroad and where two infant daughters are buried. The family apparently returned to Lovewell in the summer of 1915, allowing them to be included the following year in the 50th wedding anniversary photographs which Dave Lovewell and I enjoyed endlessly speculating about on this blog (to skip ahead to the final word on those pictures see “The Face-Maker Makes the Case”).

After Thomas Lovewell’s death in 1920 William Frank Lovewell assisted his mother in her tug of war with bureaucrats over the widow’s share of her late husband’s Civil War pension. The matter was still not settled when Frank moved his family to Wyoming in 1922. In a handwritten note withdrawing her request for a pension, Orel Jane explained the absence of her usual secretary by declaring, “He got tired of farming.”

William Frank Lovewell loved the wide open spaces of Montana and Wyoming. As early as 1917 he had placed an ad in a Montana newspaper inquiring about employment opportunities on area ranches for him and his wife. Instead he went back to his old line of work, becoming a section foreman for the railroad by the time of his death from pneumonia in 1939.

His son James Franklin Lovewell contributed a series of charming stories about his VanMeter and Lovewell grandparents when his wife Gloria undertook the formidable task of compiling a family history which was published in 1979. His memories of the senior Lovewells probably hark back to the years before his family moved to Nebraska, when he was a little tyke who saw his grandmother as a towering figure, and whose grandfather kept his short beard neatly trimmed. James Franklin Lovewell seems to have been the only family member to declare “unequivocally” that Thomas Lovewell’s first wife Nancy was Orel Jane's sister, an idea that seemed to become canon, even if it wasn’t quite true.

The idea must have been planted by his father, who as Orel Jane’s secretary had the inside scoop on family history. Perhaps William Frank recalled that the two wives were related but forgot exactly how. The pension file preserved in the National Archives reveals that Nancy Mariah Davis was Orel Jane's aunt, albeit a young one. She was only thirteen years older than her niece, born one year before Orel Jane’s parents, Vinson and Julana Davis, recited their wedding vows.

William Frank obviously didn’t share everything he had learned from working on the pension case. In her sworn deposition Orel Jane confessed that William Frank was the only one of her children who knew that she and Thomas had never been married by ceremony, and she hoped that no one else would ever find out.

Of all the well-wishers photographed by Wray the Face-Maker on April 1, 1916, only one, the man on the back row nearest to the left margin, understood the significance of celebrating the Lovewells’ wedding anniversary on April Fool’s Day.