Scott Pierce, who discovered this website years ago while he was deployed abroad and I was unknowingly providing supplemental reading material about his Lovewell heritage, sent me a link to an issue of Granite Monthly, a magazine devoted to New Hampshire history from long, long ago.

One story included in the issue, “An Old Time Trip in New Hampshire,” is an account of the journey of two young men from Dunstable, Nehemiah Lovewell and John Gilson, who suddenly decided to go exploring in the fall of 1747. Carrying a musket and a blanket apiece along with enough bread and salt pork to last five days, the men started up the Merrimack valley towards the Fort at No. 4, where forty men had recently repulsed an attack made by the French and their native allies.

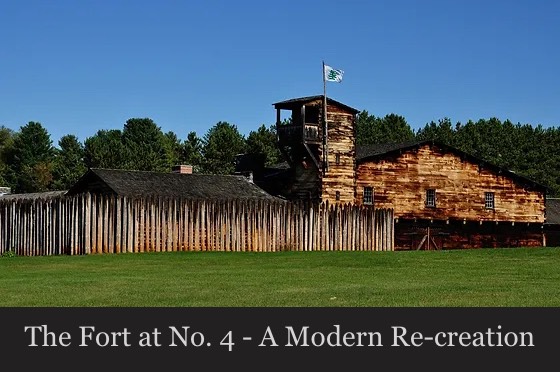

A few years before the start of what is known in America as the French and Indian War, there was King George’s War, another conflict waged between English and French colonists in the New World. The Fort at Plantation No. 4 consisted of a few houses enclosed by a palisade and garrisoned by a company of Rangers to defend the northern frontier of New England against incursions from Canada.

After spending a few days in the company of local heroes who regaled them with accounts of the desperate fight to keep No. 4 from being surrendered to the French or burned to the ground, Lovewell and Gilson decided to take advantage of a stretch of fair weather to begin their long trek homeward. The weather changed for the worse almost immediately.

They were drenched by November rains which turned to sleet and then an almost impenetrable fog, causing them to lose two days by walking in a wide circle.

On a few occasions they narrowly escaped discovery by parties of native hunters. After losing their bread in a mishap on the trail, the supply of salt pork also began to run low. The trip home seemed to be taking nearly twice as long as the journey to No. 4.

Their luck finally changed when Lovewell shot a fat raccoon which provided them with a welcome feast. Gilson climbed a tree and spotted the familiar symmetrical shape of a certain mountain that would give them a clear view of the way home. After enjoying raccoon-and-salt-pork shish kabobs prepared over glowing coals, they reached the mountain, climbed to the top, got their bearings, marveled at the panoramic view, and then retreated a short distance down the slope to spend the night in a spruce thicket.

Before daybreak Lovewell told Gilson to stay behind and prepare breakfast while he returned to the bald peak, one of the highest points in southern New Hampshire. According to the author of the piece in the Granite Monthly, Lovewell would later declare “the stars never seemed so near as when he had gained the summit.” He felt certain that he and his companion must have been the first white men ever to view the surrounding landscape from this vantage point.

I was not surprised to learn that the landmark was known as “Lovewell’s Mountain,” or these days simply “Lovewell Mountain.” From what I’ve read it could have been called that even before Nehemiah Lovewell planted his foot on the peak, said to have been named in honor of John Lovewell, the hero who died in Lovewell’s Fight in 1725, eight months before the birth of his son Nehemiah. But was it really?

According to Wikipedia, one of the sites named for the eminent Captain is that very mountain at Washington, New Hampshire, “which he climbed to do surveillance.” But if that were the case, then why would Captain Lovewell’s own son believe that he and his friend were the first white men to admire the view from the top?

Instead of Captain John, could it have been named for Nehemiah Lovewell, a man who was regionally well-known but took no scalps, inspired zero popular ballads, and whose fame was eclipsed by a legendary father who died in battle and was the subject of two songs on the Colonial hit-parade?

When Scott shared the link to this story he advised me that it involved a “Type III Adventure,” which he defined as “hard, risky and terrifying … and against your better judgment, you find yourself at it again.” Since he seemed to be identifying Nehemiah Lovewell as an adrenaline junkie, I took another look at our ancestor’s resumé.

Let’s see, he served in three campaigns in the French and Indian War, served almost continuously through the Revolutionary War, and was a Colonel in the Militia afterward. Oh, and he was the father of 13 children.

His entire life was a Type III Adventure.

By the way, the man who ordered the local militia to man the Fort at No. 4 was Massachusetts Governor William Shirley, whose name may be familiar to a small number of readers for a completely different reason.

In 1866, when Nehemiah Lovewell’s great-grandson Thomas Lovewell settled in Kansas for a second time, the county immediately to the south of his home in Republic County was called “Shirley,” to honor a civic and military leader from pre-revolutionary times. Then word got out that certain members of the Kansas Legislature were not taking their responsibilities seriously and had named the county after Jane Shirley, a prostitute from the vicinity of Leavenworth.

True or not, everyone had to admit that Jane had a larger following than a Massachusetts Governor who had been dead for ninety-five years, so the name was quietly changed to “Cloud.”

I’m willing to bet that, to this very day, Kansans who know something about Jane Shirley outnumber those who’ve ever heard of William Shirley, or, for that matter, Col. William F. Cloud. Fame can be fleeting. Infamy has real staying power.