The final chapter of "Lovewell: The Man Who Was the West" is devoted to providing instantaneous links to source material, one of the clearest advantages electronic books have over other books. Just tap one of the blue links, and, if your iPad is connected to a network, you're whisked to the associated source document straightaway. For the letter written by John G. Haynes of Clifton to Kansas Governor Samuel Crawford in 1867, I could only provide a formal citation, but also offered the opinion that by the time anyone read the citation, the letter might have joined the online collection at kansasmemory.org. Well, it's there now, and here's the link: http://www.kansasmemory.org/item/304901/page/20

The letter is contained in a collection of correspondence concerning Indian matters, all directed to the Kansas governor. Thomas Lovewell's letter, written a few weeks later, was also addressed to Crawford, but wound up in the Kansas Adjutant General's mail, perhaps because Lovewell recently had been employed as a scout and offered information about which tribes along White Rock Creek appeared to be up to no good. The very first item in the Crawford inventory may shed further light on the governor's wish to create a Frontier Battalion to protect Kansas settlers.

According to the Junction City Union, Governor Crawford was granted authority to raise a battalion of men on June 28th, 1867, only to have that authority withdrawn the very next day. He immediately wrote Senator Ross in Washington to inform him of "the true state of affairs" in Kansas, despite what Ross may have been told by agents and contractors who "represent their Indians as being at home quiet and peaceable." Crawford described some tribes as being in a state of open warfare with white settlers, but offered only one concrete example: The White Rock Massacre of April 30th.

Nine of them came into a small settlement, a few days since, on the frontier, west of Lake Sibley, murdered and scalped two men and one boy, and wounded another boy who made his escape. They then took two women prisoners. Upon one of whom each of the nine committed a fiendish outrage, and afterwards, while she was lying in a helpless condition, plunged a tomahawk into her head and left her dead on the ground, and in this condition she was subsequently found by the citizens. The other woman they took with them as a prisoner, to suffer, if possible, even a worse fate.

I have represented the condition of affairs to the Secretary of War, who from some cause, has taken no action.

I have appealed to Sherman, but he cannot engage in a war without troops or authority, so the whole subject rests with congress, either to declare all former treaties with hostile tribes void by act of war, on their part, declare war against them and furnish Sherman with a volunteer force sufficient to enable him to take the offensive...

Crawford’s description of the event differs somewhat from the offical version in the Kansas Adjutant General’s report as well as the governor’s own later memoir, and includes a sequence of events no white man could have known for certain. Thomas Lovewell, who may have been the only witness to the aftermath of the massacre to leave a first-hand account, mentioned nothing about rape or scalping. The Kansas governor's arrangement of details may have been crafted to spur retaliation by Sherman, who considered obliteration of the Plains tribes a sensible option. Since the White Rock Massacre itself appears to have been sparked by the burning of Sioux and Cheyenne villages by the Army eleven days earlier near Fort Larned, the cycle of violence seems futile. The following year Crawford would be allowed to recruit his Frontier Battalion, and the Army would track Cheyenne raiding parties in Kansas back to a winter quarters in Indian Territory. The result is known as the Battle of the Washita or the Washita Massacre, depending on one’s point of view.

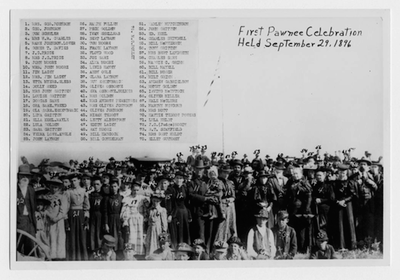

First Pawnee Celebration

The icon above is a link to a series of larger photographs residing on the kansasmemory.org website. Of the three versions of the photo, the sepia-toned original seems to contain the most detail.

Besides the Crawford documents, while dropping in on kansasmemory.org today, I also found one of the most remarkable and helpful historical photographs I've seen lately. It's a picture of a large group of Republic County citizens, gathered at the county's Zebulon Pike Monument in 1896. What makes it so helpful is a companion print of the same photograph, in which seventy-five of the people in the crowd are identified by name.

Several of those names may be familiar to readers who follow this blog. That jolly blacksmith Thomas Shuler peers out from the second row standing, on the right-hand side of the picture, amid a few other figures who helped to record and celebrate the heritage of Republic County. A surprisingly dainty-looking Lydia Charles stands nearby. I had never pictured her son, newspaper editor Gomer T. Davies, as a tall man, but it seems that he may have been one. He strikes a pose suitable for the colorful and widely-recognized figure that he was, hands hooked proudly in the lapels of his vest. All three were key players in the story of Thomas Lovewell’s “unexpected” return from Alaska at an Old Setters’ Reunion four years after the Pike photograph was taken. Shuler probably cooked up the script for the event with Lovewell, Lydia Charles stepped in at the last minute to deliver his lines, and Gomer Davies recorded the result for posterity. It’s a treat to see the three of them together in one photograph.