Sometimes when I seem to repeat myself, it’s because there’s a little something new to add to a pile of evidence that’s been accumulating for years, and instead of making readers wade through old blog posts, I try to bring everyone up to speed all at once. This one of those times.

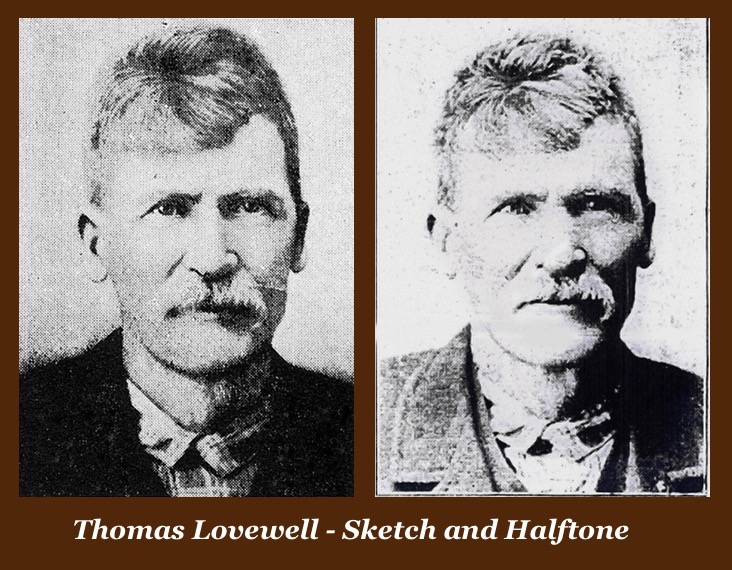

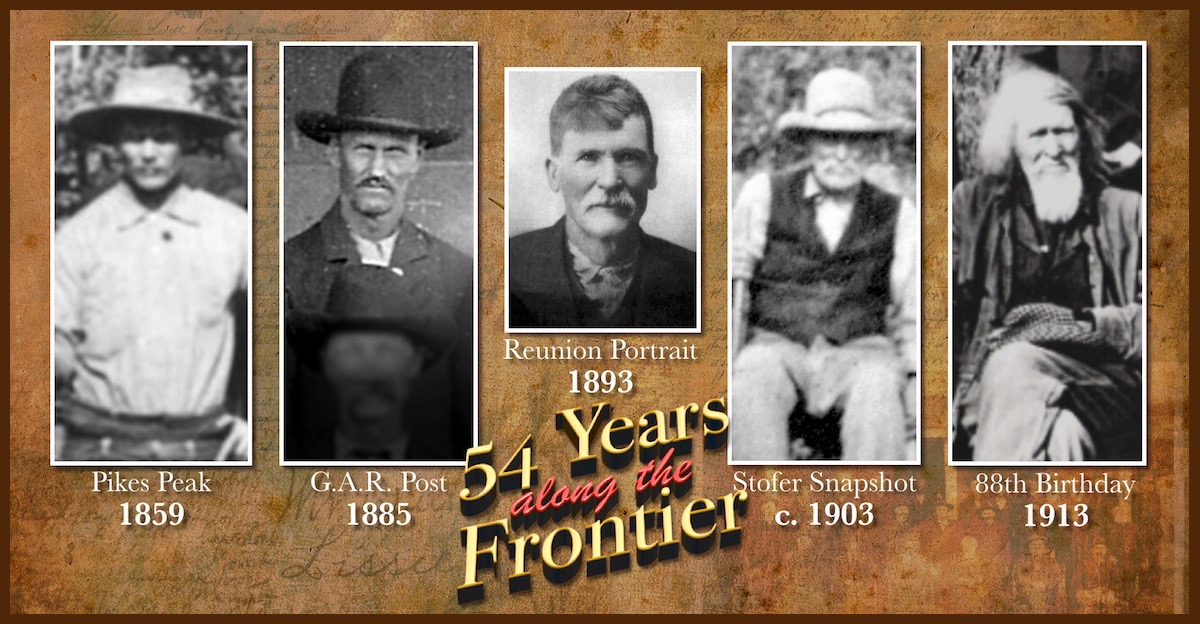

A few years ago, I had only ever seen one genuine photograph of Thomas Lovewell, taken when he was an old man with an unruly silver mane and goatee, seated on a wooden chair surrounded by adoring family members at his 88th birthday celebration.* Months later a friend sent me a picture of the same man two decades younger. Sometimes referred to as a photo, it was actually a reproduction of a sketch which turns out to be a feeble likeness.

After combing through reels of microfilm for several months, I finally uncovered a small halftone reproduced in a 1916 edition of the Courtland Register. Said to have been taken in 1893 when the subject was 67 years of age, the original photo had obviously served as the basis of that sketch my friend sent me. My own laser-printed copy from the library, blown up from a frame of microfilm of a 100-year-old newspaper image, was not exactly the detailed portrait I was trying to track down, but I was thrilled to have it, and studied it closely.

Several months later, while preparing a piece on Thomas Lovewell’s brother-in-law Daniel Davis, I logged on to Ancestry.com and sorted through family pictures until a group photo shared by Daniel’s great-great-grandson caught my eye. It took years to track down the exact provenance of the photograph, which turned out to be a record of a G.A.R. meeting at Republic City in July 1885. Thomas Lovewell’s White Rock Post had been forced to relinquish its charter, and several members, including Thomas himself, went scouting for a new home. Bumping into a previously-unknown picture of Thomas Lovewell in his 50’s was nothing compared to what was waiting for me next.

Having prepared a little electronic booklet on Lovewell’s life, I scoured the online archives of the Library of Congress for pictures that might help to illustrate it. The Denver Public Library’s “Pikes Peak or Bust” seemed a likely candidate to accompany the story of Lovewell’s journey West in 1859, although there was little information available concerning where and why it was taken. There was no writing on the back. All the library had was the name of the man who had donated it, so I started there.

After following that trail for a few years, I can say with some confidence that the scene was meticulously staged in front of a camera at Riley’s Gulch near Denver. If the photographic plate hadn’t been damaged, the picture might have joined a stack of booklets in a store window to help Daniel Chessman Oakes sell the latest edition of his guide to the gold fields north of Pikes Peak. The very first time I studied a magnified view of the astonishingly detailed photograph, I had to get up out of my chair and walk outside to clear my head.

Had my imagination gotten the better of me, or was that really Thomas Lovewell standing among the other travelers and teamsters staring back at the camera? Since that day I’ve spent hours trying to talk myself out of the idea that it’s really Thomas with his hand on his hip, as if daring someone to recognize him. Every test I’ve devised to rule him out as the tall figure immediately to the right of the damaged image of Daniel Chessman Oakes, has come up short. I was already completely convinced that it’s him, even before Ashley Gresham sent me a copy of a snapshot, probably taken by Thomas and Orel Jane’s daughter Mary Stofer, depicting her parents relaxing in their garden at Lovewell, Kansas, in the early 1900’s.

In that most recently-discovered photograph of him, we find Thomas posing with bright sunshine sculpting his face exactly the way it had 45 years earlier at Pikes Peak. It’s difficult to harbor any doubt that these are two pictures of the same man.

Using the highest-resolution photo we have of him, a version of the 1893 portrait donated to the Republic County Museum four years ago, I laid out a graph measuring the space between the pupils of his eyes, and the distance from his eyes to another horizontal line marking the bottom of his nose, then to the line of his mouth, and the distance from there to the bottom of his chin. When transferred to the man in the Pikes Peak photograph, the lattice of measurements fits precisely. The man’s eyes, cheekbones, mouth and chin all look like Thomas Lovewell’s, and are spaced the same distance apart as his were. He favors the same neatly-trimmed mustache that Lovewell did. As it does with only about 10% of men, his hair parted on the right, just as Thomas Lovewell’s did, and with that trademark low-hanging forelock that sweeps toward the left side of his face.

We know from his Army records that as a young man Thomas Lovewell stood six feet tall. While it’s impossible to know the height of the man in the Pikes Peak photo, he’s apparently long-waisted, and easily dwarfs the teamster standing next to him.

All of these resemblances might be passed off as an astonishing coincidence, if we didn’t know that Thomas Lovewell actually made a stop at Pikes Peak late in 1859 to check out rumors about a gold strike, before proceeding to Virginia City. After traveling up and down the Mississippi and living in Ohio, Illinois, Iowa and Kansas, he considered that journey to Pikes Peak the beginning of his long adventure in the West.

* We now know that the last photograph was taken April 1, 1916 on the occasion of the couple’s Golden Anniversary.