Not only was Homer Paton (pronounced Payton) known for writing poems in his youth, winning prizes for some of them in the 1920’s, but even as late as the 1960’s Homer was still hailed as the Poet Laureate of Formoso, Kansas.

Anyone strolling down the sidewalk across from the Community Church on a summer evening, might hear him passionately declaiming verses to the walls of the little cottage where he was the sole occupant. However, Homer Paton was best known for reciting someone else’s poem once every year.

On Memorial Day during the 1960’s I was enlisted to help the James Marr American Legion Post perform a traditional service over the graves of veterans at local cemeteries.

My father, who was local Sergeant-at-Arms, intoned the formal passages which stitched the program together, with a cheat-sheet typed out on a slip of paper folded in the palm of his hand, just in case. He would surreptitiously take a final peek at the paper just before the ceremony commenced, and then tuck it out of sight, though he might consult it another time or two just before his turn to speak came around again.

Homer Paton performed John McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields,” a poem I always found just a bit creepy, but one that must have held special significance for Homer because it was birthed in the theater of war where he served in the summer of 1918.

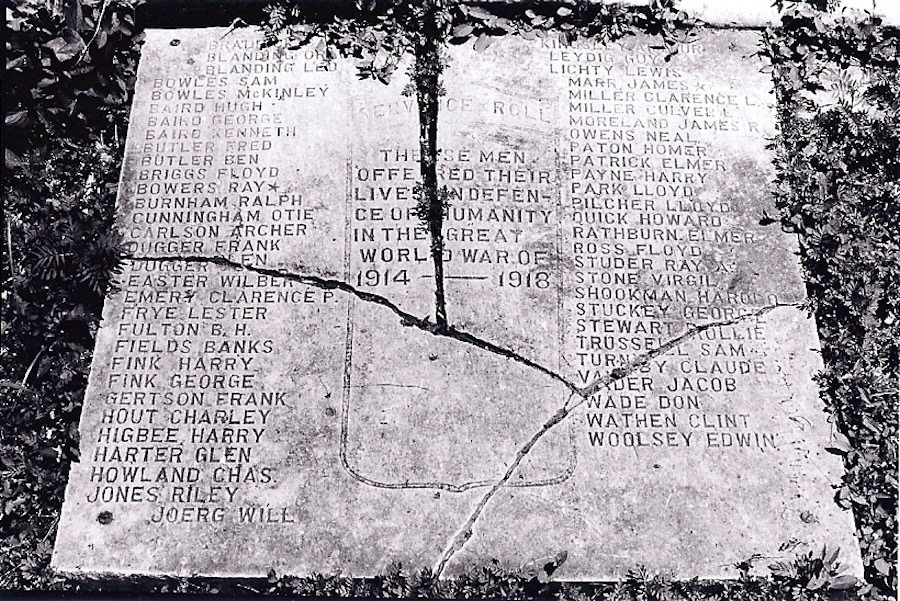

Homer’s name is among those inscribed on a marker which lay in front of the American Legion Hall in those days, as is James Marr, the Formoso post’s namesake. Marr never made it to the front, dying of pneumonia in a military hospital in May before he could ship out with his comrades. He may have been a victim of the so-called “Spanish flu.” The first documented case of the contagion had been identified in Kansas only two months before Marr’s death.

When Homer was finished I would launch into Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, an oration which takes only a couple of minutes to recite, but which also takes a few tricky turns of phrase, especially towards the end. This was followed by “Taps,” usually played on a trumpet, sometimes performed by my cousin Donna. “Taps” may be short and sweet, but it’s also not so easy to perform as you might think, especially when it’s played on only one day each year.

Hoping to find a portrait of Homer for this entry I searched a newspaper archive and found a startling item about the Paton family. This led to further revelations, as well as a possible clue to why Homer remained a bachelor.

In 1901 Homer’s uncle Robert Paton was taken to probate court on a charge of insanity. Robert was duly adjudged insane, though he was not considered dangerous enough to warrant being shipped away to the Topeka Insane Asylum. Instead he was placed under the care of a local physician for observation. However, by the time of his wife’s death two years later, Robert had become an inmate at Topeka. After he was locked away their daughter Margaret went to live with her uncle Peter and his wife Amelia near Formoso. Robert Paton died at the asylum in 1907.

A few months after his brother’s death, Peter took his own life by stabbing himself in the throat repeatedly with a pocket knife in the family’s home southwest of Formoso where they had lived for more than three decades. Peter was aware that he had begun to exhibit symptoms of the same madness which had overtaken his brother six years earlier, and decided to take matters into his own hands, waiting until his wife and children, including 13-year-old Homer, had left the house.

When Peter Paton ended his life in October of 1907, his was the third suicide to occur in the Formoso vicinity that year. It had been only four months since Peter Johnson grew despondent over losses in livestock and grain futures, and walked purposefully down the railroad tracks west of town toting a bottle of acid, setting into motion a terrible family tragedy that would claim the lives of both parents and leave two of their children injured (See “Slow-Motion Tragedy”).

As for Peter Paton, the headline over the report of his death declared:

Preferred Death to the Insane Asylum

Despite all the heartache suffered by his family, Homer Paton graduated from Formoso High School with high marks and enrolled at the University of Missouri to study journalism. Interrupting his education long enough to join a machine gun crew on a European battlefield in 1918, he resumed his studies at Salina after the war, becoming a regionally noted journalist and author.

Homer cared for his elderly mother until her death in 1937. And every Memorial Day for nearly half a century he would don a coat and tie and his American Legion Uniform Cap to tour local cemeteries, reciting “In Flanders Fields” over one of the graves where ladies of the Legion Auxiliary had placed little American flags the evening before.

By the time I joined the cast of performers at the age of 12 or 13, Homer’s voice was thin and reedy, but he spoke his lines with the gusto and conviction of a stage tragedian. As a young boy he had surely overheard services conducted over the graves of Civil War veterans such as his unfortunate uncle Robert, who had been born at Glasgow, Scotland, before the family emigrated to America, and had joined the Wisconsin 21st Infantry to fight for the Union shortly after the Battle of Gettysburg.

Thus, both recitations performed at cemeteries in the vicinity of Formoso in the 1960’s would have had special meaning for Homer Paton, even the lines his younger companion in the proceedings found slightly unsettling:

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from falling hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders Fields.

If it somehow still strikes me as just a little bit creepy, I believe the effect was intended by the author.