I must have been talking with my son about the state of TV technology in the old days. I tend to go on and on about those 100-foot loads of silent Ektachrome we went through in the late 1970’s, shooting only what we absolutely needed and editing in our heads, not only because every precious three-minute roll of film cost ten to twelve dollars, but because splices tended to break in the projector gate. Besides all that, if a roll ran out in the middle of a shoot, it took minutes to unload the exposed film and thread a fresh one while you made apologies.

“There was a sound-on-film camera with a 400-foot film magazine,” I explained, “but it took two of us to operate it, so I only took it out one time to do an interview with Vincent Price.”

A look came over my son’s face that worried me at first because I had never seen anything like it before. After being perplexed for a moment I said to myself, “Oh, I get it, this is what respect looks like.”

I hadn’t meant to indulge in name-dropping, not knowing for sure that my son even remembered much about Vincent Price, who died in the early 1990’s. On the other hand, I was proud of how well my interview with him went. I had read John Houseman’s “Run-Through” a year earlier and remembered that Price had been one of Orson Welles’ first Mercury Players, so we talked about his early stage work and that seemed to warm him up. Then we got around to what I knew was his favorite film, “Theatre of Blood,” and the way students at Billingsley Student Center at Missouri Southern demanded something from Poe and went wild when he recited “The Conqueror Worm.” It was my first and final celebrity interview as a TV newsman. If you’re only going to do one, I have to admit that I picked a good one. Of course, I didn’t bore my son with any of these details. He was simply in awe that I had chatted for a while, one-on-one with a man who, it turns out, is enshrined in his mind as a cultural icon.

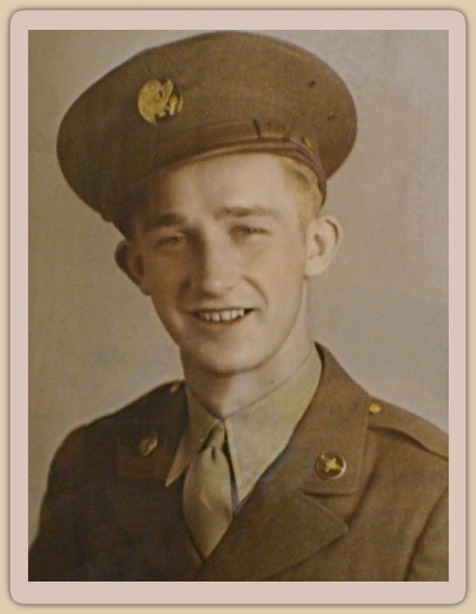

My father (pictured immediately to the left of the basketball) didn’t live to see the same expression on my face when I was clearing out personal effects after my mother died and ran across a document no one had ever shown me. It was a letter of recommendation from his commanding officer in Europe extolling my dad's versatility, which shone especially bright during an incident after his unit arrived in Poland. Escaped farm animals were roaming loose through the countrywide, so my father saddled up and began rounding up stray horses as if he had been doing it all his life. I knew he had been in Europe, but I always thought he repaired jeeps behind the front while the Army advanced through Normandy onward towards Berlin. I had no idea that he had traveled as far east as Poland, and no inkling that he had once been a G.I. cowboy.

Ironically, my father-in-law Stan, whose parents were Polish immigrants, always hoped to visit the country of his ancestors but never did. He too was shipped to England in anticipation of an Allied invasion to retake Europe, but then something dumb happened. Three generals needed to get from one side of the base to the other and Stan was commanded to get behind the wheel of a jeep and drive them. Although Stan, who got around in urban Connecticut by bus, tried to explain that he couldn’t drive, his lack of aptitude and experience did not get him off the hook. Finally shrugging and doing as ordered, he managed to put the vehicle in gear and roared away straight for an uneven patch of ground, flipping the jeep. While the generals were shaken but unhurt, Stan’s back was broken. He was discharged after only six months in the Army, but spent the next year in a body cast.

It would not be Stan’s last experience with military mismanagement. He may have been unable to drive, but Stan set land-speed records on a typewriter, able to rattle out a blazing 144 words a minute in his job as a clerk/typist. He took night classes to get his college degree and then embarked on a career as a civilian analyst at the Pentagon, just in time to take a front-row seat during the Vietnam War era. He hated the war and grumbled sometimes over the dinner table that if his girls had been boys, they would be living in Canada.

My father was also a superb clerk, who never amazed me more than when he clerked auctions. It was always impressive to observe the auctioneer pointing and nodding at subtle cues as his rhythmic chant kept the crowd caught up on the course of bidding and urged it higher. Then I realized that my father had to be tuned in to the proceedings on another level, occasionally glancing up calmly from his clipboard and jotting down a note that reminded him who had won what and how much he had promised to pay for it. At the end of the afternoon he took his place behind a card table and waited for the winners to settle up. What was he writing down on that clipboard and how could he possibly keep track of everyone in the crowd? He did have an amazing memory, able to remember by name someone he had met exactly once, twenty years earlier.

By the way, when I found that letter written by his commanding officer in Poland I also came across a cache of audio cassette tapes. When I was in radio I used to do a weekly comedy show and apparently my dad recorded every episode and forced relatives to listen to them. I hope I remembered to tell him about interviewing Vincent Price. Dad always liked his movies.