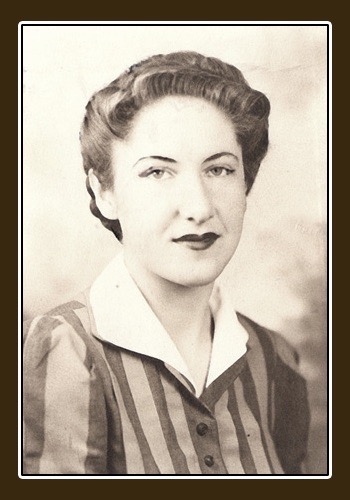

Although I doubt that anyone ever described my mother as uncommonly pretty, her senior portrait from high school presents a sweet vision of her, a moment frozen in time when she seemed to glow with youthful optimism. The miniature photograph mounted in a golden frame shows a girl with stubborn hair which has been painstakingly tamed with a curling iron into cascades of perfect ringlets, framing a face dominated by bright eyes and a smile that seems at the same time demure and innocently impish.

The senior portrait of Aunt Lillian, who was born only eight years after my mother, provides a lesson in how quickly times and fashions can spin on their axis. Outgoing and self-assured, the life of the party, Lillian was the only one of her parents’ seven children to attend college, a dream which lay far beyond my mother’s reach during the Great Depression. Mom grew up in an era of silent movies, bread lines and the Dust Bowl. She looks as if she might have been given the Mary Pickford part in the junior class play. Lillian, the baby of the family, came of age in the 1940’s and seems the very image of a World War II era foxy lady. One can imagine her holding out a cigarette and waiting for Humphrey Bogart to light it, then asking if he knows how to whistle.

I confess that I did not take a really close look at either photo until a few years ago, when I noticed that they had something in common. More than a bit of the charm and sparkle in both pictures has been convincingly added with an artist’s brush. The glow in my mother’s eyes and the firmness of her smile, Lillian’s immaculate coiffure and stencil-perfect makeup, in fact most of what immediately strikes us as distinctive personality in both photos is a sham, or at least something that has been outlined and heightened by several degrees.

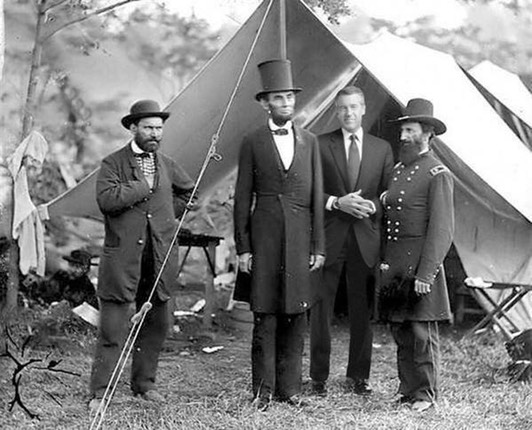

These days film dyes and camel hair brushes are old hat. We’re now all too familiar with the possibilities of Adobe Photoshop. In fact, for some time now “Photoshop” has been in danger of becoming a generic term meaning playful photographic chicanery. The recent “misremembering" business at NBC News has been lampooned online with several square yards of creatively manipulated imagery. My favorite example is the one showing Lincoln with Allan Pinkerton and General McClemand while war correspondent Brian Williams patiently waits for his exclusive interview. The prankster has selected photos with similar lighting, and has taken care to make Brian’s height look just about right when measured next to Lincoln’s 6’ 4” frame. It’s a job well done.

Those who saw the recent PBS series on the Roosevelts might remember a sequence on Lincoln’s funeral procession passing by the Cornelius Roosevelt mansion on Union Square, where young Theodore Roosevelt watched from an upstairs window along with his brother Elliott and a friend. A wid-angle photograph taken of the solemn occasion does show tiny figures at a second floor window, and a microscopic examination seems to verify the story that a future President watched the late President taking his final, meandering journey back home to Illinois.

The photograph was taken 150 years ago. A century from now will any photograph produced in our own time involving famous people, immediately fall under suspicion? Perhaps we should have been more skeptial all along. The camera doesn’t lie, we used to hear. During the Civil War the fibbing sometimes started long before the film left the camera. During that era of long exposure times, the most obliging subjects for Matthew Brady’s cameras were men slain in battle. Analysis of battlefield photographs suggests that Brady's cameramen sometimes moved and posed corpses to illustrate whatever poignant “truth" they wanted a particular photo to convey.

Today an arsenal of digital retouching software can help amateur artists make people who’ve done foolish things look like even bigger fools. It’s an extension of an art that was developed to make the subjects of portraits look their very best. They’re both a sort of lie, or at least an exaggeration.

I now know, for example, that my mother probably wasn’t quite a starry-eyed ingenue at 17, and her sister may not have been a sultry vamp with a gleam in her eye. Somebody with an ultra fine-pointed brush deliberately put those stars and gleams there.