In a chat with filmmaker Orson Welles, Peter Bogdanovich pointed out a particularly subtle camera move in the director’s Lady From Shanghai, commenting that he could hardly detect any movement at all without gazing at the edge of the screen. Welles countered that if Bogdanovich was staring at the edge of the screen in one of his pictures, he was looking in the wrong place. However powerfully our eyes are drawn to the subject matter at the center, the edge of a picture can hold its own piece of the story.

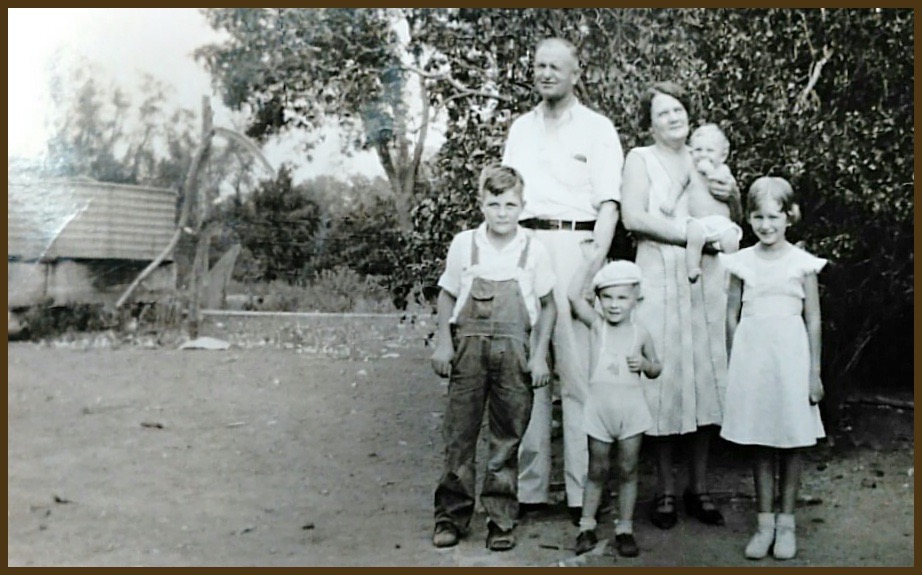

Ashley Gresham, a descendant of Benjamin J. Stofer and Mary Lovewell Stofer, has sent me a cornucopia of pictures showing the couple from every stage of their lives together, from teen years to retirement. I was going through the portraits and snapshots, cropping and arranging them into a collage for the Lovewell album page, when I stopped to take a closer look at one. It’s a photo of Ben and Mary with some of their grandkids, including Ashley’s grandfather, Norman L. Stofer, who died last October at the age of 90. Norman is the lad hitching his thumbs in the pockets of his bib overalls, striking a confident pose in front of his grandparents, who are probably in their 50’s. Looking at little Norman, I’m going to estimate the vintage of the picture as c. 1933.*

It struck me as a carelessly-framed shot and I was about to whack nearly half of the image off the left side when I began to examine the part that would be lost if I cropped it. There was nothing important, really, a structure that might be an old corn crib, and a scythe hanging ominously from a pole, items which clearly identify the setting as a farm. Nothing seems significant about that, except that sometime between 1930 and 1935, Ben and Mary moved from their Jewell County farm to Courtland, where Ben, who had been a stock buyer, went into the realty business. By 1935, young Norman’s parents, Bennie and Opal Stofer, had relocated their family to Hutchinson, Kansas. What we’re seeing may be a fond, final get-together on the family farm, before the generations were parted by the economic realities of the Great Depression.

Anyway, that’s what I read from the evidence in a background that I was ready to omit. Instead of an accident, the framing may be a poignant goodbye to a vanishing way of life.

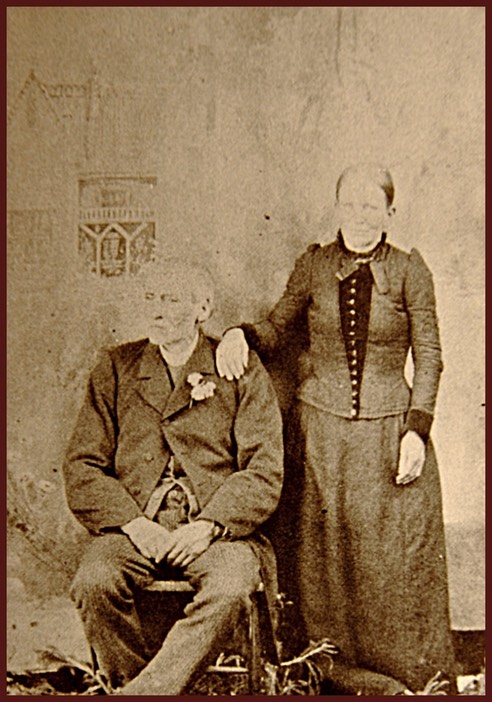

I began paying closer attention to the edges after noticing something for the very first time in another picture Ashley emailed to me, even though I had been scrutinizing my own copy of the same picture over the past decade. Not certain whether I had ever read “The Lovewell Family,” Ashley laid the book out flat and snapped pictures of a few pages containing photographs of family members, including one that might be the only extant picture of Solomon and Lucinda Lovewell.

Solomon was Thomas Lovewell’s younger brother, a man who, like Thomas himself, apparently left a young wife behind in Iowa when the Lovewell brothers made the trek to Pikes Peak and points west in 1859. Solomon continued to prospect for gold while earning his daily bread as a teamster in La Center, Washington Territory, where he lived with his second wife, Lucinda Clanton, a cousin of those Clantons immortalized by a certain gunfight that broke out on the streets of Tombstone in 1881. In the early 1880’s the couple moved to Tillamook, Oregon, where Solomon filed on a homestead near the beach at Manzanita, a beach where he sometimes mined deposits of beeswax.

Judging from Solomon’s apparent age in the portrait, I’ve always suspected that Solomon and Lucinda posed for it around 1893, the same year Thomas was photographed at the side of his long-lost daughter Juliana. I've also wondered if the two brothers agreed to exchange likenesses. The existence of Solomon’s photo was unknown to some his own descendants in the Pacific Northwest until recently, with perhaps the only surviving copy in the hands of one of Thomas’s great-grandchildren, instead of Solomon's.

What had never occurred to me until I examined the edges of the frame, is that the picture of Solomon and Lucinda was not taken in a studio. Looking through formal portraits of that era, I’ve grown accustomed to seeing people photographed among rocks, stumps, cacti, tufts of grass, even stuffed coyotes, all carefully arranged in front of painted canvas landscapes in a photographer’s gallery. However, the turf I’ve long ignored at the feet of the Lovewell couple is nothing more than a jumble of weeds and twigs. This photograph was shot outdoors in front of a makeshift canvas background in natural light.

Again, the stuff at the edges may yield clues about the specific circumstances of this portrait.**

In the 1880’s, a cameraman named Benjamin Gifford, who had trained in portrait work at Sedalia, Missouri, and Fort Scott, Kansas, went to Portland and opened his own studio. When appointments fell off after the financial panic of 1893, Gifford loaded up his equipment and traveled the countryside. If patrons wouldn’t come to his gallery, he would extend his range, bringing his camera to a wider clientele. Gifford is best known for pictures of scenic wonders of the Northwest taken on his jaunts in the country, and for Native American portraits. Many of the latter were shot on location in bright sunlight, in front of sheets of painted canvas hung from simple frames.

While Gifford is noted as one of the early portrait photographers in the Northwest, there were surely others who were forced to scrounge for paying customers during the depression that engulfed the end of the century. One of these lesser-known artists probably snapped the picture of the Lovewells. The key to finding out who made it and when, may be that sheet of canvas behind the couple. Many photographers placed their subjects in front of canvas drapes painted with dramatic skyscapes, but this one doesn’t seem to have been specially made for the purpose. It looks like a piece of some ancient, faded and water-stained theatrical backdrop.

Lately, as I’ve begun through miscellaneous family portraits from 19th century Oregon, I’ve been taking note of what’s behind the subjects. And, of course, what’s near the edge under their feet.

*After Norman Stofer's daughter, Dale Ann Johnson, asked about the other children in the photo, I had second thoughts about the date, as is evident from the next entry.

**According to Rhoda Lovewell the photo was taken by Otto Heins at Tillamook.

Stofer family photo provided by Ashley Gresham

Portrait of Solomon and Lucinda Lovewell from “The Lovewell Family” copyright 1979 by Gloria Lovewell