My high school freshman English class sometimes divvied up a script and took turns reading the parts aloud. Our teacher thought it best if we actually experienced the sounds the words made, especially when they were Shakespeare’s words, designed to fall upon the ears of an audience in a crowded Elizabethan theatre.

The play was "Julius Caesar," one of the Bard’s less exciting efforts, but one considered appropriate for young minds because there’s no sex in it, and there are no dirty jokes worth repeating. I still remember where we were in the text, which I was having a go at reading aloud, just before the whold class heard something that few of us would forget.

“Brutus, thou sleep’st. Awake, and see thyself

Shall Rome, etc. Speak, strike, redress!”

“Brutus, thou sleep’st. Awake.”

Such instigations have been often dropped

Where I have took them up.

—“Shall Rome, etc.” Thus must I piece it out:

“Shall Rome stand under one man’s awe?” What, Rome?

Then it was Stan’s turn to take over from me. “My,” he said confidently, before pausing to sound out the syllables of the word “ancestors” with painful deliberation. “…did from the streets of Rome, The” he continued slowly, word by word, before hitting a major roadblock at “Tarquin.” He stopped dead for a moment and struggled through the first few individual letters. It was an unfamiliar combination that made no sense to him, but he gamely tried to keep going until our teacher, on any other day a relentlessly cheerful lady, threw what I can only call a tantrum.

Stan, she told the class indignantly, was lazy, a disgrace to the educational system, a kid who just didn’t care, a boy who had skated by on personality for eight years, concentrating all his energy on sports without ever bothering to master such an elementary skill as learning to read. She was ashamed, so very much ashamed. Stan’s head hung low over the freshman English literature book, his jaw grazing the text that had defeated him.

None of us had ever heard of dyslexia. When I finally did, many decades later, the first thought that hit me was that it would explain how a big, cheerful, smart kid had once agonized over simple English words as though struggling to translate a page of Sumerian hieroglyphics on the fly. The second thought was for my brother, another tall, good-natured, athletic kid, one who made friends easily, a born humorist who could make anybody laugh, if he really tried. He developed multiple strategies for getting through school without having his disability discovered, the easiest being to have our mother do all his homework. He was especially proud of getting through algebra with a “B” without ever doing a problem in class. Perhaps it was a talent he devloped to help him cope, but he had a remarkable memory, especially for numbers. He read water meters for a few years in his little town, and when asked, he could instantly tell customers their water usage for any given month. He wrote me a letter once, and I believe my Tuxedo cat would demonstrate more legible penmanship if I dipped his claws in an inkwell and dragged him across a sheet of paper.

The whole matter came up again recently when a cousin told me about a strain of dyslexia running through the Lovewell family. She reported that Thomas and Orel Jane Lovewell’s son Stephen had struggled with it, as had some of his children and their children, although it was only recently that any of them learned that their tormentor had a name. Suddenly, a few casual observations took on new meaning.

The February 19, 1886, edition of the Scandia Journal reported the closing of the winter term of White Rock School on the previous Friday. The teacher, Miss Huselby, had dangled the prospect of prizes for “perfect deportment for the term, and for the best improvement in writing. The improvement in writing in all cases, was very marked. Misses Georgie and Flora Culver and George Camp received the prizes in deportment, and Stephen Lovewell and Bell Cline in writing.” Stephen Lovewell, then going on twelve years old, may have shown the greatest improvement because he had started out standing in the deepest hole.

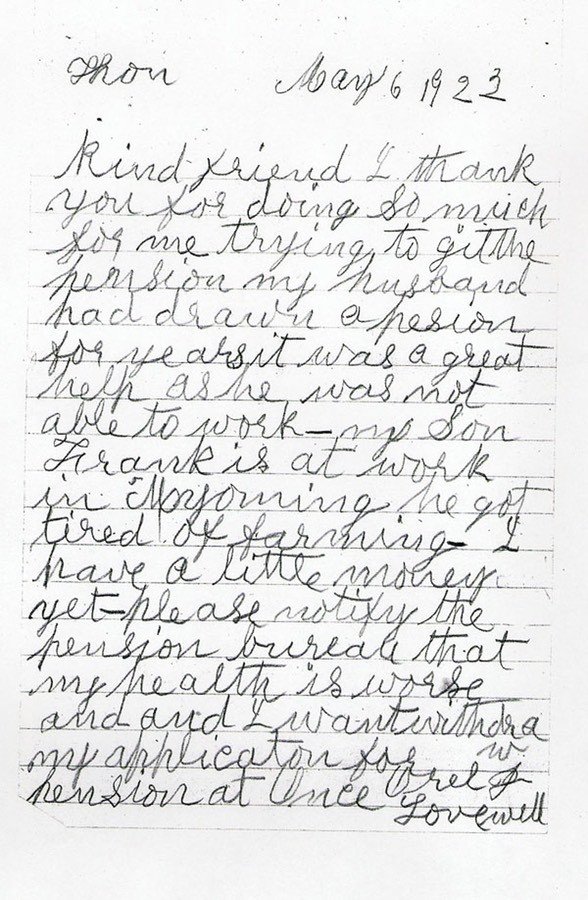

I also began to wonder about the only sample I have of Orel Jane Lovewell’s handwriting. It is preserved because of a letter she wrote in 1922 to her congressman to thank him for his unsuccessful effort to get her the widow’s portion of her late husband’s Civil War pension. The time had come, she thought, to call the whole business off.

When I first saw it, I wondered if the elderly lady might have developed a tremor (She was 79 when she wrote it). The letters are all correctly formed, but the words were obviously written slowly and drawn with great care, occasionally leaving time for her mind to wander.

Orel Jane Lovewell was a literate woman. From other sources, we know that she attended school for several years in Iowa, and she was the author of several monographs about local history. Looking at her letter, I began to wonder if the care taken in forming those letters was something she had needed to learn painstakingly as a schoolgirl back in Iowa, the way her son Stephen had to do at White Rock to earn an award as most improved in writing.

That’s my working theory for now. Perhaps when I turn 79, I’ll develop another one.