While unearthing history from old newspapers we sometimes have to keep reminding ourselves, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. On the other hand, in the world of the early-day press in rural Kansas, absence of newsprint about a prominent resident sure feels like evidence of something.

The lack of local news about Thomas Lovewell and Ben Stofer in 1901 bolsters the idea that both men were occupied elsewhere. Ben was surely in Oklahoma, where later records indicate his daughter Ethyle was born in April of that year. Thomas was either gallivanting in Alaska or scuffing his shoe against a hillside southwest of Laramie, sizing up the location for hidden mineral wealth. The only Kansas news item concerning Thomas that year was the announcement that he was preparing to return to “the Klondike” in May. Notice of a general-delivery letter waiting for him at Laramie in September, doesn’t necessarily rule out Thomas Lovewell’s return voyage to the Far North.

Laramie lay along the rail route between Lovewell and Seattle, where he could book passage on a steamer to Alaska, with a return trip planned at the end August. Perhaps disappointed once again by the Alaskan gold fields, Thomas disembarked at Laramie to have a look around. In an exclusive interview for the Jewell County Monitor in March 1902 He regaled an editor with details about a trip to Cape Nome and his investigation even further north to Cape York, but made no mention of Wyoming, a state which does not enter the conversation about prospecting for gold until later that year - after he had clearly been at it for a while.

Coincidentally, news that a letter hadn’t caught up with him is one of the earliest pieces of documentary evidence we have for Thomas’s older brother William. His name was published on a list of undelivered mail at Evansville, Indiana, early in 1844, the same year William B. Lovewell tied the knot with Charlotte Bohall in Vanderburgh County, where Evansville, the county seat, was one of a cluster of small settlements huddled along the banks of the Ohio River.

Besides that list of mail on its way to the dead-letter office, I’ve run across only two other news items that mention William Lovewell. In 1870, several newspapers picked up the story of his prowess as an angler, or at least an unusually lucky day he enjoyed late that August.

A Mr. Wm. Lovewell, of Lawrence, recently went fishing in the Kaw, and in eight hours caught 549 pounds of catfish, with hooks. The smallest fish weighed 77 pounds, and the biggest 117 pounds.

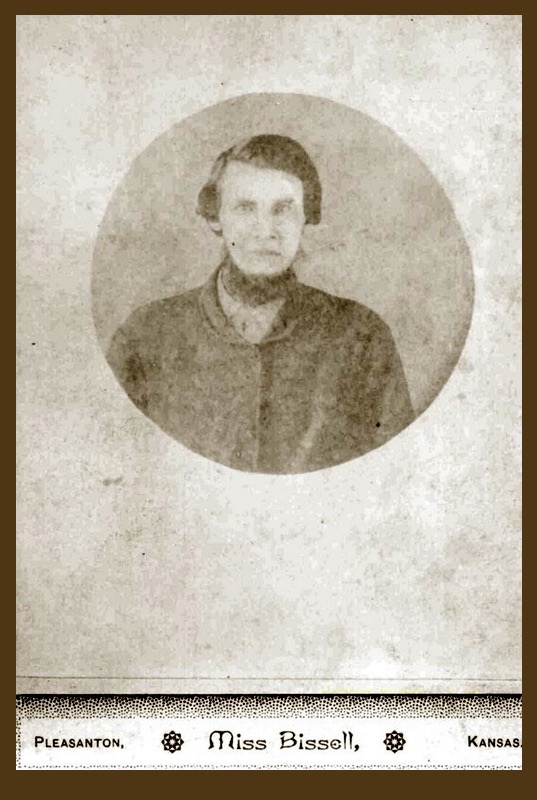

It reads rather like an algebra question in math books of the era, in which young readers would be asked to provide the number of catfish Mr. Lovewell must have pulled out of the Kaw. William lived northeast of Lawrence, somewhere between Tonganoxie and North Lawrence, Lawrence’s sister-city on the north side of the Kaw. A few years later William would move his family to Linn County in southeast Kansas, where he would sit for a tintype, the only known picture of him, made by a Miss Bissell of Pleasanton. I’ve written before about William's intimidating countenance in this likeness, but at that time I hadn’t read the story of his run-in with the law, which makes him sound like a well-recognized figure around town, one who had picked up a suitable nickname.

City of North Lawrence.

Police. - The city vs. Wm. Lovewell.

This defendant, who is sometimes called the Reverend, was arrested Saturday evening by policemen Stone and Hill, on the charge of being inteoxicated in the street, and committed to the calaboose until he became himself, when he was brought before the Mayor, plead guilty and was fined $8 and costs, which he did not lose to the city, because he coul dnot find the greebacks about his clothes. In default there of, he was ordered to stand committed, but he afterwards gave security for the amount and was released. The Reverend should remember that his Bible tells him that “strong drink is raging.”

We're often tempted to take the few facts we know about someone from the past and try to connect them into a cogent tale. Despite William Lovewell’s best efforts to keep a low profile, we’ve learned something of the character of his third wife from the memoirs of his daughter LuNettie (see The Lord of Ringgold), and have to wonder if William occasionally hit the bars of North Lawrence to escape from the much-younger but shrewish and hot-tempered Matilda.

Perhaps he moved to Linn County after hearing that the catfish grew even bigger in the Marais des Cygnes River. My own guess is that he just wanted a quiet spot far away from a city with a daily newspaper, where he could continue to fly under the radar.