The photograph of Grandma Logan which I resurrected from a deteriorating celluloid slide a few weeks ago, also brought back memories of a bookcase, a treasured copy of a classic novel, and a movie which I could not image ever being able to see. And yet I finally have, after sixty years of waiting.

The bookcase is visible beside the couch where Lillian Logan poses with her newest grandson, Jimmy Dieckman. Inside those glass doors lay a book containing unimaginable treasures. The book was the Boy Scout Edition of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, which featured photographic plates from a film adaptation released in 1916.

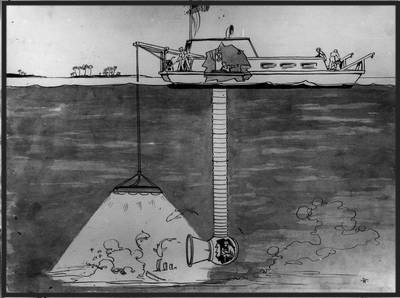

The groundbreaking silent film was made possible by an innovation in undersea photographic gear developed by the Williamson brothers, who apparently were encouraged to take a much-deserved onscreen bow during the opening credits.

If I had never been afforded the opportunity to watch the silent 20,000 Leagues, it would have marked the second time a filmed version of the novel appeared to lie forever beyond my reach.

The 1954 Disney epic had been on my radar since I was somewhere between two and three years old and running around the neighborhood clutching a movie tie-in published by Dell Comics. On the cover was a diver in underwater gear brandishing a knife as he faces a menacing shark which seems about to lunge toward him.

I once stabbed my older brother Ron in the tummy with a hunting knife after he agreed to play the shark in a reenactment of the scene. He cried “Ow!” and examined the spot under his shirt where the point of the blade had touched. It hadn’t pierced the skin or the fabric, but he seemed shocked at what I had pretended to do. Hadn’t he understood the inherent danger involved in playing the shark? Some people.

I thought of that incident many years later as I was lying on the floor of my living room when my two-year-old son suddenly toddled up and smacked me in the eye with a steel ladle. I don’t know what scene he was reenacting but I laughed every time I examined the shiner he gave me. Sometimes Karma can be hilarious.

Anyway, back to 1954, when my parents managed to buy me off with a screening of Beneath the 12-Mile Reef at the Princess Theater in Scandia, Kansas. It would be my only visit to the Princess, which closed a few years later. I remember wandering out of my seat and getting up close to the screen just in time to watch a rubbery octopus menace Robert Wagner, who plays a sponge fisherman off the Gulf Coast of Florida. I was very keen on natural sponges and deep sea diving helmets for about a year afterward.

I finally did get to watch the Disney film almost half a century after its initial release, when the company issued a two-disc DVD in 2003. It was worth the wait. I’m not sure three-year-old me would have appreciated the craftsmanship displayed on the screen. The incredible squid attack at the climax of the film had to be staged twice and proved so costly that it threatend to bankrupt the studio, at least that’s how the story goes. As a moviegoer I had been quite satisfied with the sluggish octopus of 12-Mile Reef.

After examining the photograph taken sixty years ago in my grandmother’s parlor, I suddenly decided to check the status of the silent film teased in that Boy Scout Edition of Verne’s novel. Why not? Old films and TV shows are constantly being dusted off and uploaded to YouTube.

Lo and behold, the film in question has not only been rediscovered and resurrected, but painstakingly restored, polished to a high sheen and given a sumptuous orchestral score. Grabbing a bowl of popcorn I was finally able to see how the 1916 film solved the plot problem of the book.

The plot problem of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is that there isn’t any. In Verne’s novel Professor Aronnax and his team are brought aboard the Nautilus, allowed to marvel at its futuristic refinements, and then go on an epic sightseeing cruise. The submarine gets in and out of one pickle after another and then, just before being swept up in the mighty Maelstrom that portends almost certain doom for the ingenious craft and all hands, the three guests suddenly decide to jump ship. Lucky for them. The end.

The team at Disney injected suspense into the proceedings by making the entire film the story of an epic jail-break. The guests are prisoners who are always on the lookout for a chance to escape, and find it at the last possible moment, just as they have come to sympathize with the tortured soul of their captor.

The screenwriters for the silent film conjure up plot complications by padding out the cast of 20,000 Leagues with characters from Verne’s sequel, Mysterious Island, and then fashioning a few flashbacks which explain Nemo’s backstory in exhaustive detail. Some of the flashbacks come early on, but the most crucial are withheld until very near the end. It’s a bit like watching a version of Cast Away where at the end of the movie Tom Hanks suddenly remembers having been stranded on the island by Johnny Depp as Captain Jack Sparrow from Pirates of the Caribbean. And then the credits roll.

While fairly entertaining, the movie is actually much weirder than I’m making it sound. Viewers are treated to attempted assaults, suicide, genocide, violent revolution, loads of waving kelp and some evil-looking barracudas. If you want to give it a try, scoop up two bowls of popcorn and have a spare bag ready to toss into the microwave. At barely 90 minutes long, the film is actually much shorter than it seems.

Sketch of the Williamson contraption courtesy Chapman University Digital Commons