Over the past few years I’ve looked through dozens of pages of mortality statistics to try to get a handle on just how deadly a place the Old West was, and how long it took before things started to improve. Often, the information is presented pictorially, in a colorful graph. If the data tiptoes across the century mark, it must invariably scale one tall, slender peak, an Everest of death with a little flag perched on top, commemorating the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19.

Even as early as October 1918, a doctor writing an article in the Washington Times admitted that the pandemic had been misnamed, having little to do with Spain, except for being the site where troops apparently performed a dizzying maneuver, according to an accompanying map. The article, which seems to have been a carefully-crafted piece of propaganda, reassured readers that “no plague epidemic of such magnitude as those of the past can occur in America at the present time. How widespread has been the outbreak of Spanish Influenza is shown by the fact that our Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, suffered from it, while, at about the time he was recovering the youngest son of the King of Sweden died of it.”

The paper did not elaborate, but, significantly, Prince Erik of Sweden was in his late twenties, a prime candidate for this strain of influenza, which struck hardest at healthy young men and women with mature immune systems. They were the ones who seemed to develop pneumonia, leading to “wet hemorrhagic lungs, fatal in from 24 to 48 hours” according to an Army study.

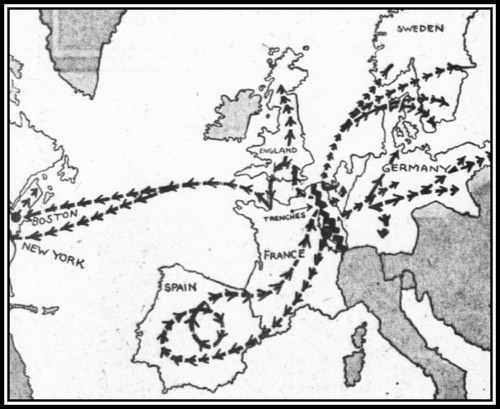

Dr. Gordon Henry Hirshberg informed the American public that the disease had originated in the German trenches, arriving on American shores with the Norwegian ship Bergensfjord on August 12, but he also passed along the transparently apocryphal report “that the German U-boats surreptitiously disseminated the infection in this country.” Most sources now agree that Spain was a convenient fall-guy for the pandemic, because it was neutral during the war and had nothing to lose from being fingered as a den of contagion. However, the map appearing with Dr. Hirshberg’s article in the Washington Times had almost everything about the spread of the pandemic completely backwards.

I remember reading in my fifth grade history textbook how before joining the fray, newly-arrived American troops marched down the boulevards of Paris announcing, “Lafayette, we are here!” Besides repaying a debt to a French hero of the American Revolution, the soldiers may have brought an unwelcome guest.

Studies since the twenties have thrown suspicion on the United States as the source of the pandemic, and have recently trained the spotlight on Haskell County, in western Kansas, as a probable ground-zero for this deadliest mutation of the flu bug. According to an online article from the website of the Journal of Translational Medicine, a country doctor named Loring Miner was so alarmed by what began happening to his neighbors that he quickly warned public health officials.

In late January and early February 1918 Miner was suddenly faced with an epidemic of influenza, but an influenza unlike any he had ever seen before. Soon dozens of his patients – the strongest, the healthiest, the most robust people in the county – were being struck down as suddenly as if they had been shot. Then one patient progressed to pneumonia. Then another. And they began to die. The local paper "Santa Fe Monitor," apparently worried about hurting morale in wartime, initially said little about the deaths but on inside pages in February reported, "Mrs. Eva Van Alstine is sick with pneumonia. Her little son Roy is now able to get up... Ralph Lindeman is still quite sick... Goldie Wolgehagen is working at the Beeman store during her sister Eva's sickness... Homer Moody has been reported quite sick... Mertin, the young son of Ernest Elliot, is sick with pneumonia... Pete Hesser's children are recovering nicely... Ralph McConnell has been quite sick this week (Santa Fe Monitor, February 14th, 1918)."

The epidemic got worse. Then, as abruptly as it came, it disappeared. Men and women returned to work. Children returned to school. And the war regained its hold on people's thoughts.

Local boys who had been called up to report for duty brought the sickness to Camp Funston, where 1,100 men lay ill in the hospital at one time, while their fellow soldiers lined up, first at railway stations, and then at docks, to carry the outbreak across the waters of the Atlantic. Coming up with a worldwide death toll is a guessing game, but, in addition to Downton Abbey’s fictional Lavinia Swire, the pandemic may have claimed something on the order of 60 million lives. Over half a million victims died in America, where the average life expectancy plummeted by twelve years, almost overnight.

By 1918 the modern world had made great strides in recognizing the importance of hygiene, and it had learned to innoculate against many preventible illnesses. Unfortunately, it had also built a superhighway that could speed contagion from the sod dugouts of western Kansas to the rest of the world in a matter of days.