I first made the acquaintance of Helen Jewett almost exactly 135 years after her murder.

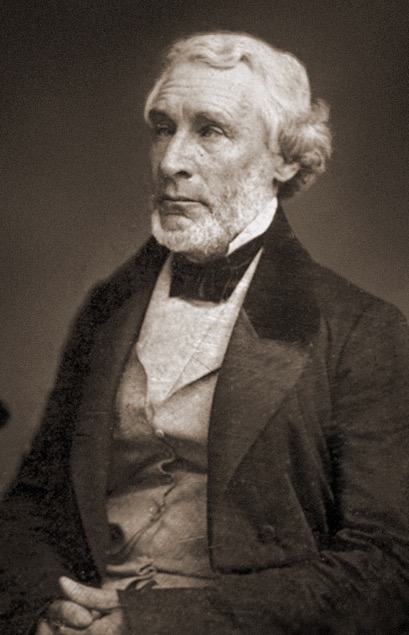

Introductions were arranged at a classroom in Kedzie Hall at Kansas State University, during a course on the history of American journalism. The instructor, a spirited young professor named Carol, who would later take the helm of the department, was a completely-smitten admirer of James Gordon Bennett,Sr., editor and publisher of the New York Herald. Bennett, a cross-eyed editor, according to Carol (She suspected that all 19th-century newspaper editors were cross-eyed, and backed up her hypothesis with a slide show), was an innovator whose Herald is sometimes recognized today as the prototype of a modern newspaper. The story that propelled the Herald ahead of other Penny Press titles vying for the pennies of New York readers in 1836, was the murder of Helen Jewett.

Before Bennett’s Herald, newspaper coverage of the death of a Manhattan prostitute was sometimes limited to a rousing page-one limerick, full of double entendre. James Gordon Bennett sensed that there was something out of the ordinary about this case, and that it called for extraordinary treatment. While his competitors might fabricate whatever details they believed the public wanted to read, standard practice for the time, the Herald editor took the unprecedented step of visiting the crime scene in person late in the afternoon after Helen Jewett was killed in her bed by three blows from a hatchet, and the bed clothes were set on fire. Bennett poked about the room, had a look at the victim’s decor, her small collection of books and her fine wardrobe, apparently spoke with a witness, and published the interview. Such a thing had never been done before.

Born Dorcas Doyen at Temple, Maine, the young woman who called herself Helen Jewett was reared in the household of a Maine Supreme Court judge, whose private library may have allowed the girl to cultivate a taste for literature, although she also attended common school, where she was reported to be a quick study. Contemporary moralists speculated that it was her passion for novels that led to her ruin, and pointed to her unfortunate example when urging other young women not to read them. The April day when she was killed, Jewett was only twenty-two, admired as a great beauty with expensive tastes in clothes, and a fiercely independent spirit. She was intelligent, well-read, and, it turns out, a shrewd manipulator of her clients.

How Dorcas Doyen became Helen Jewett, and how she came to be killed by one of the young men who paid to sleep with her, is the subject of “The Murder of Helen Jewett” by Patricia Cline Cohen, published in 1998. I was unaware of the book before running across an old C-Span video of Ms. Cohen giving a talk about her book, but when I realized that she was speaking about a young woman with whom I already shared a past, I knew I had to get a copy.

The light which Patricia Cline Cohen’s book sheds on journalism, jurisprudence, and everyday life in New York in the 1830’s is fascinating. The trial of the accused murderer, a man in his late teens, reminded Ms. Cohen of another murder trial, one that kept America transfixed at the very moment she was researching and writing her book. In both cases, even though the killers had left behind damning evidence, their trials resulted in acquittal. The presiding judge in 1836 gave what amounted to a directed verdict, instructing jurors that they must give less credence to the testimony of persons of low character, by which he meant most of the witnesses in the case, residents of the house kept by Rosina Townsend, versus anything said by a solid citizen. For anyone reading her book today, Ms. Cohen also unknowingly points us toward a crime that had not yet happened when she wrote it, when she mentions that the high-class Manhattan brothel where Helen Jewett plied her trade before being bludgeoned with a hatchet, was, in 1998, part of the grounds of the World Trade Center.

The murder of Helen Jewett happened just as word arrived in the city about the other big news story of that spring, the fall of the Alamo, with the loss of all her defenders. It’s a reminder that history is written in blood. That’s not to say that 1836 was a banner year for bloodshed. There was plenty of violence in New York in 1836, but the actual homicide rate was negligible. The people who write history, however, like the people who read it, tend to be drawn to the gory stuff. It's a lesson that a Scotsman named James Gordon Bennett learned early on. Bloodshed sells papers, and fixes both the perpetrators and their victims in our memories. There is a very good chance that David Crockett, while celebrated in his own time, would be utterly forgotten in ours if he had not sauntered into San Antonio just in time to take refuge in the Alamo, along with a few other people who are also remembered, chiefly because they died with him there.

So it is with Helen Jewett, who limited herself to ten clients a week, charging them five dollars each, making over twenty times as much as a girl her age could make working in the mills of New England. If she had saved her money, she might have returned to rural Maine after a few years, a woman of means.

And we would know nothing of her.