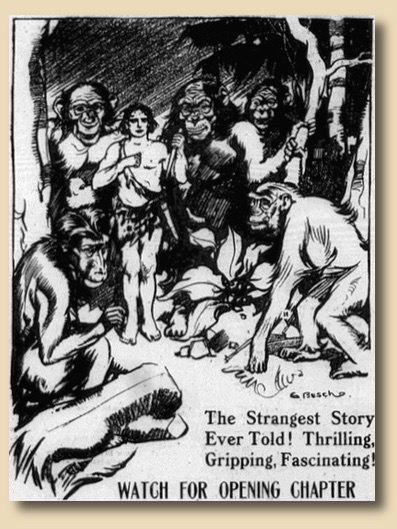

I had the story from one who had no business to tell it to me or to any other. I may credit the seductive influence of an old vintage upon the narrator for the beginning of it and my own skeptical incredulity during the days that followed for the balance of the strange tale.

I do not say the story is true, for I did not witness the happenings which it portrays.

With this modest preamble, Edgar Rice Burroughs launched his adventure story about the orphaned son of an English couple, shipwrecked castaways who perish in the African jungle shortly before their newborn baby is adopted by an ape. In addition to the small library of Tarzan books that Burroughs cranked out, there would be seven silent films followed by forty more in the sound era, a few movie serials and a TV series, a comic strip, comic books, and bubblegum trading cards. The Tarzan industry, which has taken a breather in recent years, is bouncing back with a new film scheduled for release in 2016.

The very first book in the series, “Tarzan of the Apes” was published in 1912, arriving on the doorsteps and inside the mailboxes of subscribers to the Lovewell Index in 1914, an era when getting the local paper was akin to being a member of a book club. After Lovewell area residents had finished digesting Thomas Dixon’s “The Root of Evil,” many of them dived into Burroughs’ strange and thrilling tale.

My grandmother was born in Portland, endured a few years of grinding poverty there and in St. Louis, but spent the bulk of her youth in Lovewell. She was the 27-year-old wife of a blacksmith when she first escaped for a few hours into the daydream world of a faraway jungle and its unlikely ruler. It was at my grandmother’s house several decades later when I was seven or eight years old that I had my own first encounter with Tarzan. In her front parlor she kept a small metal wastebasket that contained several issues of Tarzan comics from the mid-1950’s. In content, the comic books had little to do with the popular Tarzan films of that era, although they did feature beefcake publicity photos of actors Lex Barker and Gordon Scott on the covers.

Barker inherited the job of impersonating Edgar Rice Burroughs’ jungle hero from Johnny Weissmuller in 1949, handing off the role to Scott in 1955. Lex Barker and, at least initially, Gordon Scott, would spend their careers as men of the loincloth repeating Weissmuller’s stunted “Me Tarzan" vocabulary. However, for his final two entries in the Tarzan canon, Scott would be called upon to play the Lord of the Jungle as Burroughs had written him, as my grandmother’s favorite Tarzan comics always portrayed him: an articulate nobleman who would have been perfectly comfortable in a tweed suit and starched collar, chatting about world affairs with Lord Grantham at Downton, though he much preferred to leave the fancy threads behind and hang out in his boyhood home in Africa, near the first family he had ever known.

Tarzan is as familiar an icon as Robin Hood or Zorro, and nearly everyone has an image of him, though seldom is that image one Edgar Rice Burroughs would have approved. His Tarzan’s first spoken language (Besides “Ape”) was French, taught to him by a naval officer named Paul D’Arnot, who was also conversant in English, but decided that his own native tongue would be much easier for him to teach. For Burroughs, the choice of French as Tarzan’s first tongue may have been a nod to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the philosopher commonly associated with the concept of “the noble savage,” a social theory for which Tarzan may have been the last great standard-bearer.

First-time readers are usually surprised to discover that the climax of “Tarzan of the Apes” takes place, not in darkest Africa, but in northernmost Wisconsin, and ends on a romantic cliffhanger. The inevitable sequel was first called “Monsieur Tarzan,” before Burroughs came to his senses and settled on “The Return of Tarzan,” which was also serialized in the Lovewell Index, for subscribers who were sitting on pins and needles waiting to learn whether Tarzan got back together with Jane Porter. He did.

The Tarzan series was not without controversy. The librarian at Tarzana, the California town that took its name from Burroughs’ nearby ranch, refused for a while to allow any Tarzan books on the shelves, citing, as I recall, their outmoded ideas about white supremacy, colonialism and the British class system, or something like that.

Was Burroughs a racist? Several volumes from the pen of fellow writer Thomas Dixon, including Dixon’s Klan trilogy, occupied a shelf in Burroughs’ private library. It is possible that Burroughs made his other great hero, John Carter, a former Confederate captain as a tribute to Dixon. Thomas Dixon’s ideas about race may have persuaded Burroughs to populate Mars with white, black, red, yellow and green races of men. It also occurs to me that one can gaze way too deeply for hidden meanings in what was intended to be a ripsnorting potboiler.

An even more senseless brouhaha developed when someone pointed out that Tarzan and Jane were never legally married, at least in the MGM film series with Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O’Sullivan. Their marriage in the books was not contested, since, if Downton Abbey has taught us anything, it is that an English earl could not have run off to the jungle with a young unmarried American girl without creating an international scandal. It would have been in all the papers.

As for the films, someone postulated that Jane’s father was an ordained minister who united the couple in the holy bonds of matrimony before their treetop tryst. Just shows you that there’s always someone out to ruin our fun.