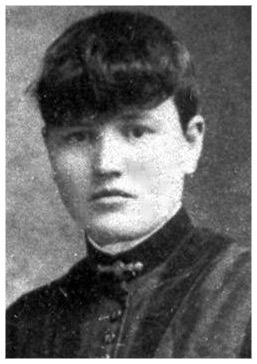

The picture of the girl with short, dark hair has been in my folder of Lovewell family photographs for a few years now. I believe it was cousin Jack from Alexandria who sent me the likeness of one of his ancestors, but I could be wrong. He might have been wrong, too.

The young lady is said to be Martha Jane Honts. Martha is the girl I wrote about a few days ago, the one who married Thomas Lovewell’s brother Christopher Wolfe Lovewell in 1856 and gave him four children before he was killed at Vicksburg in May of 1863. Cousin Jack is descended from Christopher and Martha’s youngest daughter, Sarah. In the wake of my posting about the paltry number of grandsons among Moody Bedel Lovewell’s children in 1863 (See “Girls, Uninterrupted”), I discovered a letter from Jack reminding me that William, Christopher’s only son, had no children. With today’s lower birth rate, I sometimes hear family elders bemoaning the end of the family name in their own line. My point in writing that piece was to show that even back when having twelve children was common, surname-extinction was still a worry. In 1863 the Civil War was a major winnowing factor. After the deaths of hundreds of thousands of men, some family names must have gone with the wind. On the other hand, it was an excellent time for the mitochondrial DNA business.

Twenty-five-year-old Mary Jane Honts Lovewell applied for a widow’s pension the following August, going down a road that makes much of the rest of her life an open book for family historians. We know that she married disabled Army veteran Amos Singleton, the brother of Joseph Robert Singleton, the man her sister Alvira had married. After Amos died in 1884, she next married John Stone, whom she outlived by eleven years, dying a penniless widow in 1919, one who would have been a charity case if not for the small pension earned by Christopher Lovewell’s sacrifice fifty-five years earlier.

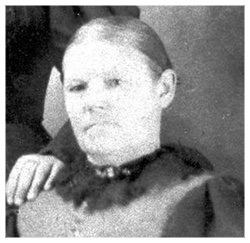

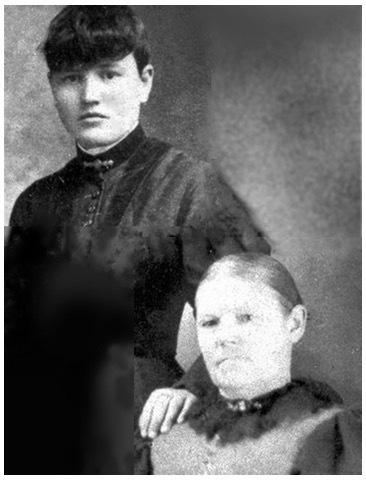

It was touching to see the photograph of her as a young woman, taken perhaps a year or two before she married Christopher Lovewell at the age of nineteen. Looking for her family on findagrave.com I found a picture of her sister, Nancy Eveline Honts South, and the family resemblance is undeniable. Then I was struck by something else about the two pictures. They fit together quite nicely to show that they are really two sections of a larger family portrait (I’ve provided a bit of airbrushing to help make the case), but one that just doesn’t feel quite right. I’m no expert on fashion or hairstyles or even the history of photography, but this portrait looks as if it would be much more at home on a parlor wall in the 1880’s than in a keepsake cabinet in the 1850’s.

On another point, born in 1837, Martha Jane Honts was the eldest daughter in her family. If the photograph is supposed to depict her as one of a pair of sisters, Martha Jane should be the one sitting down. But that doesn’t seem possible either. Only about ten years separated Martha Jane from any of her siblings, and I doubt that the two women in the portrait were born one decade apart. Nancy Eveline Honts, identified as the seated woman, was five years younger than Martha Jane. Add in the fact that the hairstyles, dresses, and lighting all seem to suggest a post-bellum photograph, and the younger woman simply cannot be the Honts girl Jack was told she was. She might however, be a Lovewell. She could be Martha and Christopher Lovewell's daughter, Sarah Emaline Lovewell, who was my cousin Jack’s great-grandmother.

Sarah Emaline Lovewell Ennis was a true homebody. Born in Warren County, Illinois, in 1862, she and her husband lived there until 1890 when they moved to Galesburg in nearby Knox County. She died at age 67 and was buried not far from the old farmstead in Warren County. Holding true to the Lovewell family’s odd run of luck with boys, her only son, Giles Ennis, died at 18 of erysipelas and septicemia. She was survived by three married girls.

If anyone reading this happens to hold another piece of the Honts family mosaic, please let me know.