If you have a cherished family portrait, be sure to scour every inch of it. Every inch. Always check the margins and, of course, turn it over. You never know what seemingly-innocuous detail might hold an important clue. A year ago I wrote an entry, “Familiar Honts,” about how a hand resting on the shoulder of Nancy Eveline Honts South in a photograph on Findagrave.com proves that the picture of another young lady sometimes identified as Christopher Lovewell’s bride, Martha Jane Honts, must be someone else. The subject could actually be Christopher’s daughter, Sarah Emaline Lovewell, but that’s only an educated guess. All we know for sure is that it can’t be Martha Jane.

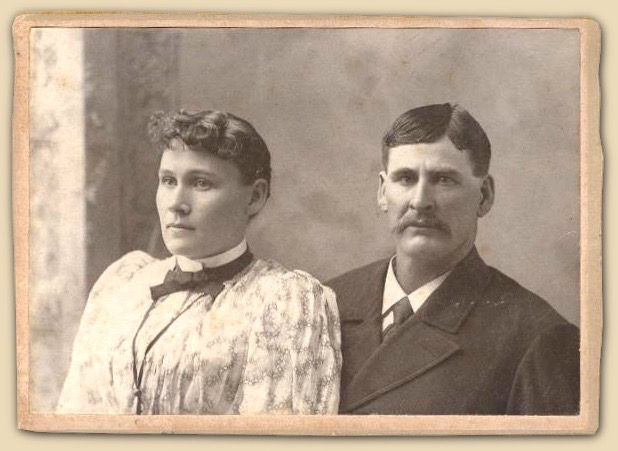

One famously misidentified portrait in Gloria Lovewell's “The Lovewell Family” is the one presented as “Julaney (Lovewell) McCaul Robinson and her husband, John.” In reality the picture to the right commemorates the reunion of Hepsabeth (Lovewell) Robinson’s children, Rhoda and John (no relation at all to the John Robinson who married Thomas Lovewell’s eldest daughter). The ladies who uncovered the mistake are Barb Gray and Bev Craig, who are the female subject’s great-granddaughters. It was an entirely understandable error, since the name of the gentleman staring so fiercely at the camera was John Robinson, and Rhoda Robinson, who was Thomas Lovewell’s niece, turns out to bear a striking resemblance to his daughter.

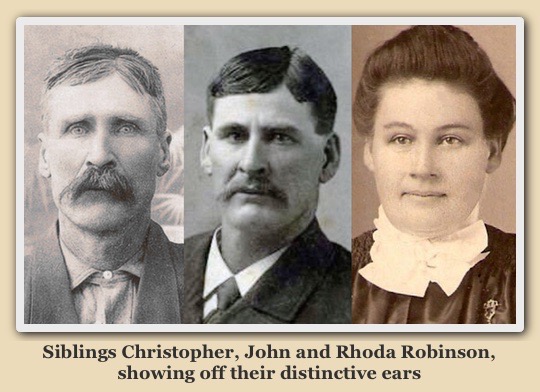

Even if there had been no writing on the back of Barb and Bev’s copy of the photo, another picture Barb shared with me should have been enough to throw a monkey wrench into the original identification. It’s a likeness of Christopher Columbus Robinson, who has not just the same fierce gaze as his brother John, but ears with the same distinctive undulations.

Viewed head-on, the outlines of their ears flare out at the bottom, swoop inward and upward, and then make a final elfin flourish near the tip. It’s not obvious in the picture of Rhoda and John, where she appears in a three-quarters view, but in another portrait of Rhoda with her brother Christopher, we discover the same elegantly tapered architecture in her ears.

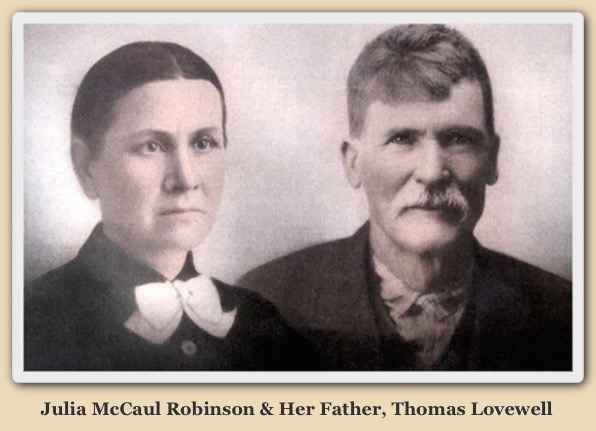

At the Lovewell reunion two years ago someone produced a photograph of a man and a younger woman, identifying it as a portrait of Thomas and Orel Jane Lovewell. I realized about a day later that the woman in the picture could not be Thomas’s wife, and was instead almost certainly his eldest daughter, born in Kansas Territory in 1857. The photo of Thomas seems to be the original version of a halftone engraving that appeared in several Kansas newspapers early in the 20th century, and which graces the banner at the top of this website. It also must have been the basis for a pencil drawing that was for decades the only familiar likeness of Thomas Lovewell as he appeared in rugged middle age. After learning from an item in the Courtland Journal that the photo appearing in the paper in 1916 had been taken in 1893, I spent months combing through newspaper archives, looking for some occasion that would have prompted Thomas to pay a visit to a portrait studio.

Finally, I realized that the occasion for the photo-op had to be the father-daughter reunion that occurred in 1893, when Thomas rescued Julia McCaul and her children from the miserable poverty the family endured in a St. Louis slum after Edward McCaul plummeted from the roof of a railroad depot. It also occurred to me that my theory worked only if the 1893 picture of Thomas Lovewell turned out to be half of a double portrait. That idea was validated in 2013 when the photograph to left was unveiled at the Lovewell family reunion, before being presented to the Republic County Museum. However, if I had taken a closer look at another drawing printed in “The Lovewell Family” in the 1970’s, I could have saved myself some time.

The piece of artwork, which is captioned “Orel Jane in her younger days,” seems to be a freehand rendering of the woman seated beside Thomas Lovewell in the recently-unearthed photograph, reimagined as a stern governess who has just bitten into a sour persimmon. What should have been obvious to me all along is that the woman in the drawing is seated next to a companion, who has been all but cropped out of the composition. Only his shoulder remains, barely visible just behind hers. A faint oval outline around the woman suggests that the two figures were once part of the same drawing, but were later matted, framed and hung separately.

Photographic portraiture was all the rage in the 1880’s and 1890’s, and the reunion of long-separated family members made an excellent excuse to troop off to a gallery. For instance, John and Hepsabeth (Lovewell) Robinson’s children were scattered after their father’s death in 1878, with John, Jr., and Orin growing to manhood in Thomas and Orel Jane Lovewell’s house.

Thanks to Barb Gray, I have some eight or nine photographic mementos of get-togethers among that batch of nine Robinson siblings. Anyway, I believe the folks in those pictures are all Robinsons.

I haven’t taken a close look at their ears yet.