In 1893 with a looming public relations disaster on his hands, Thomas Lovewell began rounding up help to contain it.

After spending the last 34 years apart, Thomas was reunited with his eldest daughter late that summer or in early autumn. For many of those years of separation the girl's mother, Thomas’s estranged first wife Nancy, had assured Julia Lovewell that her father was long dead, a casualty of the Civil War. Two years old when he had trotted off for Pikes Peak, Julia made a last-ditch effort to locate him in 1893 when she was ill with six starving children in her care and a crippled husband languishing in the Missouri Southern Railroad Hospital at St. Louis. Thomas hopped on the next eastbound train, scooped up his daughter and her children, brought them to Lovewell, and installed most of them in one of the houses he owned near his farm north of town.

It sounded like the sort of tear-streaked family reunion story newspapers were always ready to pounce on. Thomas made the rounds of newspaper offices that fall to make sure they didn’t print a word about it. Too many secrets might come tumbling out.

When chatting with neighbors Thomas probably never volunteered information about his first marriage, the one he walked away from in 1859 as he emarked on an extended ramble in search of riches supposedly waiting at Pikes Peak, Death Valley and Virginia City. Not only had Thomas seemingly deserted his first wife, instead of picking up where he left off after coming home to Iowa in 1865, the 40-year-0ld adventurer found an eligible woman slightly more than half his age, his wife’s niece, Orel Jane Moore, and left for Kansas with her.

Opening a window into his own colorful past was probably the least of Thomas’s worries. His daughter’s reputation was the more immediate concern. Julia had arrived in Jewell County with six children in tow, three McCauls and three little Robinsons. The McCauls, Eddie, Willie and Alice were her children by her first husband, Edward McCaul, who now lay dying in St. Louis, after tumbling from the roof of the great depot he had been working on. The youngest of the Robinsons was Julia's own 6-year-old daughter Lillie, her child with John Robinson, a man who may or may not have been a bona fide second husband (probably not). The two others Robinsons, Marie and another Alice, were apparently the product of a brief marriage between John Robinson and Julia’s stepsister Susie Turnbull. It was all very complicated and would provide fertile ground for gossip about a young woman in fragile health.

After their meeting, one local editor was moved to publish a rhapsodic tribute to the old pioneer, extolling his legendary generosity and largeness of spirit.

Our old friend Tom Lovewell, of White Rock, than whom there is no bigger souled man on earth, was over to the city Monday and favored us with a call...

Of all else you might say of Tom, no man need ever pass his door hungry; he would divide his last loaf of bread or peck of potatoes, and has often done it, yet he is to-day well to-do...

He was unfortunate to have over $1,200 locked up in the Courtland Bank failure, but that don’t seem to worry him as much as the present administration’s actions toward the old soldiers, of which he was one, and we venture to say a good one at that. Tom spent the day in town hunting up and shaking hands with old timers, every one of whom was glad to meet him.

The State Exchange Bank of Courtland padlocked its doors on July 31, 1893. Fifteen miles down the road, the State Exchange Bank of Jamestown followed suit on August 7. In each case there were rumors that the cashier had cleaned out the vault on his way out the back door. Bank closings were not unusual in 1893.

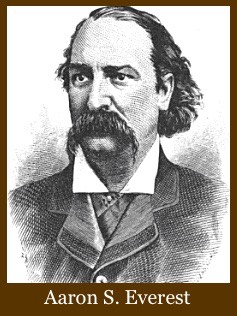

Also suspending business that same year were the Belleville Bank and the Republic Valley Bank at Clyde, among the 500 or so banks and loan institutions that were shuttered across America as the country braced for a long and cruel depression. Situated such a short distance apart, the banks of Courtland and Jamestown had something else in common. A principal investor in both was a railroad lawyer from Atchison named Aaron S. Everest.

Everest had made his fortune representing the Missouri Pacific Railroad when railroads were in the ascendant. His health went into a steep decline around the time it became clear that railroads were vastly overextended and his own banks were on the skids. When he died the following year the Brown County World in Hiawatha gave his passing a pointedly brief mention.

AARON S. EVEREST DEAD.

Col. Aaron S. Everest, who got our people to vote Missouri Pacific bonds, is dead.

Col. Everest continued to make news from time to time for a few years following his death. In September 1895 the Topeka Daily Capital carried the following item:

Mrs. A. S. Everest Sued for $69,000

Special to the Capial.

Atchison, Kan., Sept. 27 - F. A. Lane receiver for the defunct State Exchange bank of Jamestown, Kan., filed a suit in the district court today to recover over $69,000 from the widow of the late Aaron S. Everest. The petition alleges that the bank was managed in the interests of Everest and that before the bank closed in 1893 Everest drew out the entire capital, in addition to other money.

If the Courtland Bank failure didn’t worry Thomas Lovewell much in 1893, the matter must have nagged at him on reflection. Plaintiffs were lining up to file suit against Everest, his widow, or his estate in the matter of the Jamestown bank. Two years after the death of Aaron S. Everest, the Atchison Daily Champion printed a small item relating to Everest’s other bank in north-central Kansas.

Thomas Lovewell, of Lovewell, Jewell county Kan., has brought suit in the district court against Marie M. Everest, executrix of Aaron S. Everest estate, for $6,000. The suit grows out of the Courtland Exchange bank in which Col. Everest was interested.

I’ve seen no record of the outcome of any of the suits, but have to assume that Mrs. Everest held on to the bulk of her husband’s estate. In 1903 Marie M. Everest went to bed in good spirits at a home near her daughter in St. Louis where she had retreated after her husband’s death, dying in the night of what was reported as apoplexy.

The elaborate house Aaron S. Everest’s railroad money built in Atchison continues to occupy a prominent spot on the town’s historic homes tour. The daughter Thomas Lovewell sought to protect from scandal in the fall of 1893 died of cancer the following spring. Her father's mission had been so effective that only one newspaper breathed a word about her death, a paper that did not exist when he embarked on his public relations tour. Even then, there was nothing in the obituary that connected her to him.