Over ten years ago my friend and research mentor Barb Gray advised me to write down everything I learned and not throw anything away; if it meant nothing to me immediately, it might in the future. That advice came in handy most recently when I was examining a preview of some Google Books and came across a name that I not only recognized, but one that gave a little tingle when I read it in context. The book was “To the Pike’s Peak Gold Fields, 1859,” a volume I happen to own, having purchased it years ago after learning that Thomas Lovewell headed there that year. The volume is a collection of diaries of men who followed the various paths to Pikes Peak that existed in 1859: the Arkansas Route, the Smoky Hill Trail, the Platte River Road, and the Leavenworth to Pikes Peak Express, with a section devoted to one leg of the journey along a path from St. Joseph to Fort Kearny.

I skimmed the book immediately after buying it, hopeful of stumbling across some mention of Thomas Lovewell or one of his two younger brothers, Alfred or Solomon. While I was disappointed in that regard, there remained plenty of information to be learned about the process of getting from one place to another in 1859. Some of the creeks and streams had been bridged, evidently by the government. Crossing others, as well as major rivers such as the Missouri, was usually done by ferry or steamboat, at a cost of $1.50 to $2.00 per wagon with their oxen. Migrants making their way toward Pikes Peak on foot, and there were many of these in 1859, paid 50¢ unless several competitors were vying for the foot traffic, in which case, fording a river might cost as little as a nickel.

Several of the men keeping diaries of their journey were obviously well educated, able to jot down learned notes on the exotic flora and fauna and striking geological formations they encountered. When I finally picked the book out of the stacks piled on my bookshelf, I had a good time revisiting those accounts, which contain some of my favorite anecdotes about travel on the frontier.

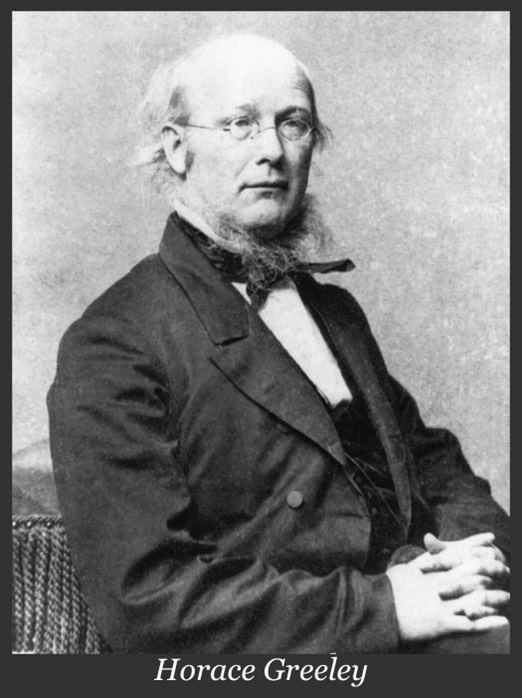

One of the best is the story of the awestruck Indian girl at a station near Manhattan who pointed at the stage and then announced to a new arrival, “That’s Horace Greeley in a big old white coat in there!” It’s funny to imagine that absolutely everybody seemed to know who the editor of the New York Tribune was, and could recognize him on sight. (It might be time to remind readers that Horace Greeley was a Lovewell relative; Captain John Lovewell’s niece was Horace Greeley’s grandmother). Later in the journey, when a bull buffalo slowly approached the coach, the diarist grabbed his Sharps Rifle and fired several shots into the front of the beast, who took little notice before finally losing interest altogether and wandering away. Greeley urged the man to shoot at others in the herd, since he seemed to take some enjoyment from the activity, and the buffalo didn’t mind.

The incident would be more amusing if it weren’t also typical behavior of the reckless bunch streaming toward the gold fields. They shot antelope, sometimes for food, but often just to see how many each man could bring down. The graceful animals seemed to spring up in such an abundance that one or two less, hardly seemed to matter. At one point, a group of travelers fired on an eagle’s nest and were disheartened to find it so solidly built that their bullets couldn’t reach the eaglet nestled inside. In the main, they acted like a bunch of neighborhood hooligans trampling an absent homeowner’s garden, when they thought no one was watching.

What newspapers sometimes characterized as “The Insane Rush Back” seemed to take hold in early May. The diarist recording his own group’s progress along the Platte Road estimated the traffic flowing eastward was five times as heavy as that headed toward Denver, but took heart from observing that those turning back were the ones who seemed ill prepared to give the gold fields a proper test. Many had used up their provisions getting as far as they had, and needed to beg meals along the way home. Several of these were men who had tried to make the whole trip on foot, sometimes pushing handcarts containing their meager belongings. It was during the period covered by this diary that D. C. Oakes lugged his steam-powered sawmill from his former home at Pacific City, Iowa, to Riley’s Gulch, near Denver.

Oakes had become so efficient at frontier travel that he could make the trip in only ten days, when unencumbered. Frustrated by the slow progress on this journey, he raced ahead to do some prospecting north of Denver, then doubled back to oversee the transporting of his mill. Oakes became enraged when he found himself being blamed for inciting the stampede toward Pikes Peak, and even buried in effigy along the trail by disgrungled prospectors. A mound of dirt amid scattered buffalo bones was marked with an epitaph which read, “Here lie the remains of D. C. Oakes, who was the starter of this damned hoax.” Daniel Chessman Oakes was only one of twenty men who contributed guidebooks to the recent gold rush. In fact, the booklet he was accused of writing was largely penned by someone else. Oakes had, indeed, published the pamplet, but besides that he had merely contributed helpful information about the most convenient route to the gold fields. However, he was the one whose named rhymed with “hoax.”

Over the past few years, every I scrutinize the photograph taken near Denver in 1859, I wonder how those particular men happened to assemble in front of a camera pointed at D. C. Oakes’ campsite. The obvious answer is that they all met somewhere along the journey West.

Oakes must have made the acquaintance of several travelers in 1859. He not only made the trek back and forth between Pacific City and Denver three times, but took a side trip to the gold fields in May, returning to his wagon train in time to guide it to Riley’s Gulch. The author of a journal written along the Platte River route that year records seeing him twice, both sightings occurring about the same time another wagon train is mentioned - the Williamses from Michigan. Seeing that name is what gave me a tingle of excitement last week.

There was, after all, no record of John H. Williams of Michigan joining the Pikes Peak Gold Rush in 1859, aside from a photograph that shows a man who looks like him, wearing suspenders and a ridiculously large white hat. John and his father and brother from Cornwall probably made much of their journey by rail, disembarking at the final stop on the recently-completed Hannibal and St. Joseph Railway. There, they probably ran into the Lovewell brothers while they were purchasing their gear. Somewhere, there’s a written record that puts them all at the scene. There has to be. Because they’re all in the picture together.