It was the late Barb Gray, a descendant of Hepsabeth Lovewell Robinson, who first suggested that while looking into Moody Lovewell’s family I had overlooked someone.

Actually I had given short shrift to several people, particularly Moody’s daughters. Like most 19th century women they had left a shorter paper trail. For instance, they were never arrested for public drunkenness or rustling horses. The girls didn’t sign up to fight in their country’s wars, or go West to file mining claims, or drop by the local newspaper office to give the editor an earful, and all the other things Lovewell men sometimes did. However, the person Barb was referring to was a man who hadn’t done any of those things either.

“What’s the deal with Moody Jr.,” she asked.

Born 287 days after his parents’ wedding, Moody Lovewell, Jr., never married, living at home until his father cashed in his chips, at which time he moved into the household of his sister Hepsabeth at the age of thirty-five.

Checking my email history I noticed that I hadn’t bothered Mary Penner lately. Besides being a professional genealogist and an award-winning writer, she’s one of Moody Sr.’s descendants who would never have left this particular stone unturned. Sure enough, she remembered that the elder Moody’s probate record mentioned a guardianship for his firstborn son, labeling him a “lunatic.”

Barb Gray wondered if Moody Jr. had suffered from cerebral palsy, saddling him with learning difficulties that made him forever dependent on his family. “Lunatic” makes the situation sound worse, but some words can have that effect.

Seeing the cause of death written on Joseph Taplin Lovewell’s death certificate last year made me catch my breath for a moment. His death, coming months after the icy fall that fractured his hip and left the brilliant Kansas scientist helpless and bedridden, was ascribed to “senility.” Of course I was thinking of the word in a modern sense, as a synonym for senile dementia. What the medical examiner meant was that Professor Lovewell had died of the natural infirmities expected in a man of 85 years.* His aged body had simply given out. He had not necessarily spent his final days staring blankly at family members as he struggled to remember their names, or howling at the moon like, say, a lunatic.

After being adjudged insane in 1904, Moody, Jr.’s niece Mary Lovewell of Mound City, Kansas, was sent away to the Osawatomie State Hospital for the remainder of her life. In fact she’s still there, buried in the old hospital cemetery north of town. Her headstone is inscribed with a number, the treatment we might have expected of interments in the village graveyard in Patrick McGoohan’s 1967 TV series The Prisoner. There’s something sinister about having someone’s identity scrubbed, even in death. It’s like being disowned for eternity.

Moody was luckier, being surrounded by family members for his entire life, but especially lucky if the word describing his condition was aptly chosen.

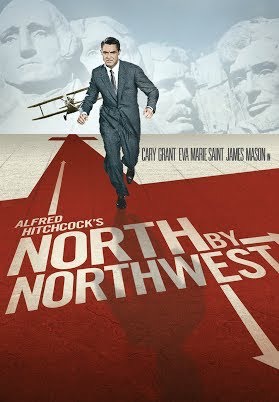

Although “lunatic” eventually became just another word for “insane,” a lunatic’s disorder was once thought to surface only on occasion, much as Hamlet described his own state of mind as dependent on which way the wind blew: “I am but mad north-northwest.” Alfred Hitchcock famously appropriated the description for his 1959 spy thriller North By Northwest, a film in which nothing quite adds up, but nobody really minds. Or, as the title character muses in the director’s 1960 follow-up, Psycho, “We all go a little mad sometimes.”

Some just venture a little further off the deep end than others.

*That’s an 85-year-old a century ago. We’re all going to be just fine.