Put yourself in my shoes. I’ve grabbed every spare moment for the last two weeks to craft a short video about the closing of the American frontier at the end of the 19th century, from the point of view of the Lovewell and Stofer families. Virtually the last words of the script involve Thomas Lovewell’s return to Kansas after a year engaged in prospecting at Cape Nome, Alaska Territory.

For some time I’ve been hoping that the newspaper archives from Courtland, Kansas, would finally be available on the Internet, making them easier to search. Immediately after posting the finished video on Youtube I discovered that my wish had been granted. It’s a lesson in being careful what you wish for.

After typing a search for “Thos. Lovewell,” practically the first result that popped up was an announcement from a September 1900 issue of the Courtland Register that the Kansas pioneer had returned from a sojourn lasting scarcely more than three months, having journeyed not to Cape Nome, but to the Klondike. Leafing through issues published earlier in the year, I found item after item about his plans for prospecting in the Klondike, and his delay in getting there because of difficulty securing passage from Seattle. At last came news that he was about to board a ship soon to be steaming away toward the Klondike, carrying with him the best wishes of the neighborhood press, who felt certain that if any local man was going to make a sizeable gold strike in the continent’s newest frontier, it would be the area’s oldest frontiersman and most notable prospector.

The 1979* standard volume of family history, The Lovewell Family, reports that Thomas Lovewell went to Nome in 1898 (an unlikely year, as I’ll explain). Offering a condensed version of a story told by Thomas’s granddaughter Orel Poole in 1958, the book describes how, at the Old Settlers’ Reunion near White Rock, local historian Lydia Charles was interrupted during her quavering recitation of the perils facing old-timers in Alaska, when Thomas proclaimed his return by stepping out of the crowd and taking the stage to recount his adventures.

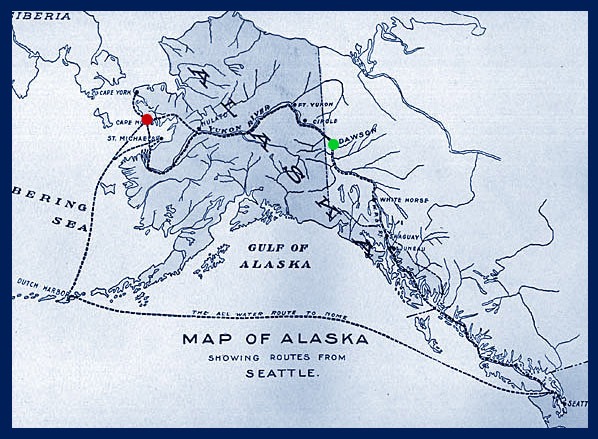

It was a moment somewhere between high drama and low comedy, and I’ve suggested that, far from being a surprise to Lydia, who was also the Old Settlers’ Association President, it was probably a carefully-rehearsed bit of vaudeville the two had cooked up. Display ads publicizing the event in area papers had promised an address, followed by a “response from an old settler.” But, rehearsed or improptu, did the exchange happen in 1898 or 1900, and had Thomas recently returned from Cape Nome or the Klondike? As a map of sea routes from Seattle shows, the two popular destinations were a thousand miles apart. With only a bit of overlap, the mad dashes for wealth were also separated by time.

The rush to the Klondike got underway in 1896 and was petering out by 1899. Attention had turned to Nome in 1898, but not until after September, when gold was discovered on the beaches. While the Kondike was fraught with danger, prospecting in Nome was a lark. There was hardly even any need to file a mining claim; a hopeful explorer simply pitched a tent to establish squatter’s rights and commenced sifting sand.

What’s becoming clearer with the arrival of new bits of information, is that Thomas’s mining trips were prolonged and frequent, and the full story of his Alaskan adventure was evidently more complicated than the charming tale of the Old Settlers’ Reuion suggests. After returning home in late summer of 1900, Thomas was reported the following May to be gearing up to have another go at the Klondike. The story of his meeting with cousin Joseph T. Lovewell of Topeka in 1902, states that he was already making summer excursions to the mining region around Jelm, Wyoming, a pattern he would follow at least through 1908, the year he turned 83.

When Thomas chatted with a reporter long enough to produce a skimpy synopsis of his life, published at the start of 1916, papers declared that “within a few years ago he spent a year prospecting in Alaska.” He may have stayed there for the bulk of a year, not all at once, but in aggregate. As for his exact destination after departing Seattle, it might be useful to remember that separate newspapers in Republic County put him at Cape Nome and the Klondike in the summer of 1900. After four years of printing stories about millions of dollars in wealth being hauled out of the Klondike, the word had become a generic term, a synonym for “bonanza.”

In fact, when Kansas papers printed the name “Klondike” in 1900, they were often referring to a saloon district near the Old Soldiers’ Home at Leavenworth. Shrewd entrepreneurs had opened a string of grog-houses near the hospital in a last-ditch effort to separate aged veterans from their pensions. It must have been a Klondike for somebody.

Anyway, I’m not changing the video. Not yet.

* A typo used to give the year of publication as 1879. It was fixed in 2022.