Since learning of its existence in November 2015, I’ve held out a slight hope that I might someday see the only known photograph of Stock Whitley, the Deschutes chief better known to students of Lovewell history as “White Lily.” Readers of Roy Alleman’s fictional retelling of Thomas Lovewell’s life story, The Bloody Saga of White Rock, may know Whitley by still another name. Alleman calls the Indian “White Feather,” because of the Army scout’s alleged practice of wearing a single white feather in his hair to let soldiers know he was on their side.

In 1864 Stock Whitley was serving as chief of scouts for an expedition along the Crooked River intended to launch a surprise assault on the outlaw Paulina and his elusive band of Paiute marauders. When the plan went sideways, four attackers were killed outright, including Lt. Watson, one of the two officers in command. Counting the eight more men hit by bullets or arrows, the opening salvo had taken nearly a quarter of the expeditionary force out of action. The soldiers were forced to withdraw, leaving many of their wounded to get back to the bivouac point on their own, while allowing the surviving renegade Paiutes to escape.

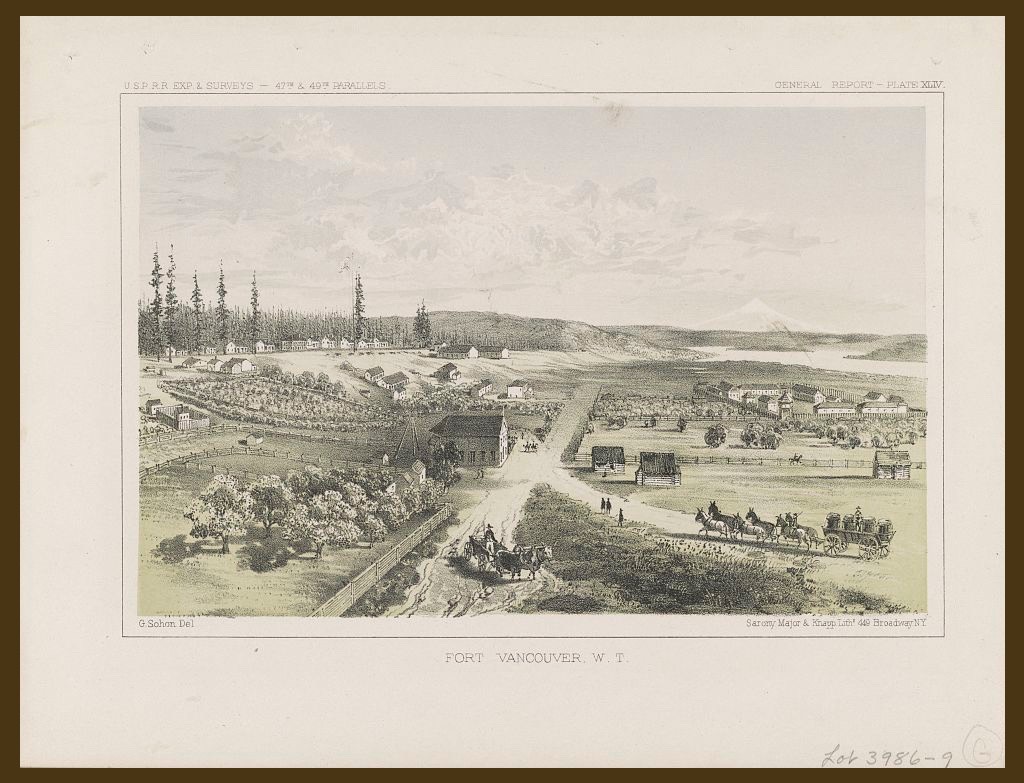

In his initial report on the failed expedition written in his headquarters at Fort Vancouver (pictured below), Captain John Drake offered the opinion that, while Whitley’s injuries were quite serious, he would probably recover. Standing well over six feet tall with a husky build and a seemingly indomitable will, Whitley must have given the impression that there wasn’t much that would kill him. When he died of his wounds weeks after the battle, snippets from a letter first published in the Oregonian in May 1864 were reprinted in several newspapers, describing how “although almost shot to pieces,” he had lumbered away from the battle “like an old grizzly” to receive medical attention. An acquaintance of Whitley’s who quoted from the letter eulogized him as a fierce warrior who had gone down “fighting like a Spartan.”

Recently I came across a copy of the entire letter written to the Oregonian, which describes the aftermath of the Crooked River fight in some detail, and contains a vivid summary of the injuries suffered by Whitley and some his comrades. I’ve highlighted portions of the letter that apply specifically to Whitley.

Lt. McCall then drew the troops off a short distance and sent a courier to our camp and Company G was immediately dispatched to his aid but when they arrived the enemy had flown, leaving all of his household goods and other property to fall into the soldiers hands.

The Warm Springs Indians, in the meantime had driven off the band of horses. So after setting fire to the wigwams and heaping on bushels of Indian muckamuck and other articles of every description, we came rapidly away, bringing with us our dead and wounded. The Indians loss in this short fight must have been considerable, as many were seen to fall and the rocks were covered with blood where they were entrenched. They left but one of their dead upon the field, and him they partly concealed with old hides.

The killed are Lt. Stephen Watson, Co. B, 1st Calvary, Oregon Volunteers, privates, James Harkinson, and Kennedy of Co. B, 1st Oregon Cav. and an Indian, whose name is not known to me. The wounded are as follows: Corporal R. Daugherty slightly wounded in the shoulder with an arrow; Privates George Freeman, slightly wounded in the chest with an arrow; Jas. Weeks, slightly wounded in the wrist with an arrow; John Level, slightly in the side with an arrow; William Henline, seriously in the shoulder with a bullet, all of Co. B. Mr. Richard Barker, (citizen) seriously with a bullet in the thigh, fracturing the bone; Stock Whitley, a well known Indian seriously in three or four places with bullets, one of which entered just under his ear and came out of his mouth carrying away two teeth, another fracturing his collar bone, and others made flesh wounds in his back and arms; still another Indian received a slight bullet wound, and this completes the list of casualties.

Old Stock Whitley showed himself a brave man on the battleground, and although almost shot to pieces, walked off to where he could receive assistance, like an old Grizzly. The surgeon pronounces all of the wounded men to be out of danger. Poor Watson’s last words were, "Pour it into them Boys.”

After the funeral yesterday, we were conversing upon the sad duty we had just performed, and it was remarked, that though public opinion did not so vote, it was just as deserving of praise to die here in the discharge of one's duty as it would have been to fall at Chickamauga or Gettysburg…

The final paragraph of the piece suggests that even by 1864, some volunteers in California and Oregon may have been smarting from the Army’s refusal to transfer them east to join the fight where eternal glory was being won. Chasing Indians around the wilds of northern California, Oregon and Washington Territory was not the duty many of them had signed up for.

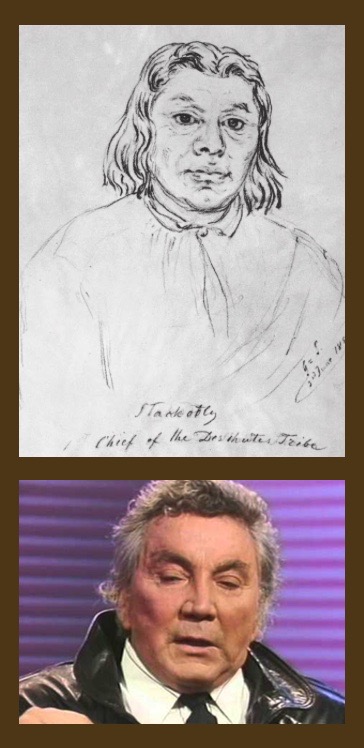

While the one photo of Whitley once known to exist hasn’t surfaced so far, a book on Oregon military history published in 2016 contains a contemporary sketch of him, and I’m happy to settle for that much. The sketch was one of a series made by Gustav Sohon in 1855, when a series of peace conferences were being held, and is held today in the collection of the Washington State Historical Society.

I’m not sure what the description of Whitley as “the most noble-looking Indian I ever saw” led me to expect, but it probably wasn’t a face with some resemblance to American film actor Cameron Mitchell, most familiar to TV viewers who might remember him from “The High Chaparral.” Yet, there it is.

The drawing from the book Images of America: Oregon Military also slightly muddies the waters concerning the chief’s real name. The subject of the sketch as written at the bottom, is “Stock-Ote-Ly.” And he didn’t look that much like Cameron Mitchell.

But he did, a little bit.

For the previous posting on Stock Whitley click here to see “Stock Photo” from November 2015