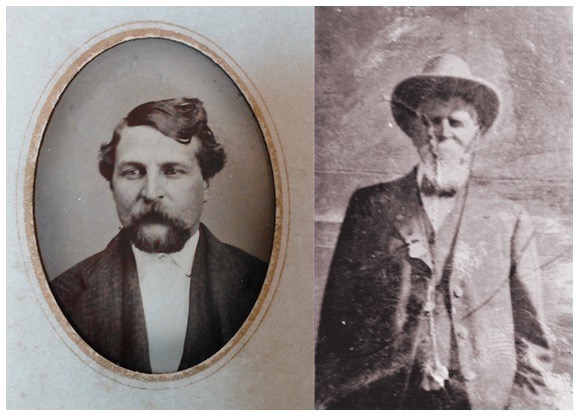

There’s a pleasing symmetry in the fact that Jacob G. Stofer’s adult life is framed by a pair of photographs that probably started out as tintypes. He had the first portrait made shortly after the end of the Civil War when he and his new bride Nancy were on the verge of leaving Illinois for Iowa, and posed for a second one on a visit to Fairbury, Nebraska, nearly fifty years later.

A few days ago I suggested that some sort of quick-and-dirty tintype process might have been selected for the tchotchke Jacob picked up at the Sells-Floto Circus in 1915, because the simple chemistry involved in developing tintypes saved time and effort.

Since the occasion being celebrated was the farewell tour for “Buffalo Bill” Cody, it didn’t hurt that the result automatically seemed like an antique, an appropriate look for a souvenir from an era that was just then taking its final bow. Tintypes, sometimes known as ferrotypes, are easily distinguished from the ordinary black and white photographs in most of our family albums.

Honest-to-goodness tintypes were produced on lacquered iron plates. They also relied on a chemical cheat, turning the camera negative into a positive image by dunking it in acid. There was a tell-tale downside to the resulting picture; it remained a mirror-opposite. Thus, in the early photo of young Jake, his hair parts on the right side, which in this case is wrong. Although the top of his head is concealed under a hat in the photo of 70-year-old Jake, the buttons on the left side of his coat still give away the technique.

Keepsakes shared by Stofer descendants offer a whole catalog of the tricks-up-the-sleeves of friendly neighborhood portrait photo-graphers. The costliest of them may have been the matched pair of likenesses of Jacob G. Stofer and his wife Nancy, suitable for mounting on a parlor wall. While large-format portrait cameras produced photos adequate for showing off in a cabinet, there were hand craftsmen who specialized in cranking things up a notch.

Some of these painters and sketch artists were more talented than others, and some clearly needed to rethink their career path. The artistic embellishments on the photograph of Nancy are unobjectionable, except for making her appear slightly dizzy, but I’m not sure what to make of the portrait of Mr. Stofer, who seems to have been caught posing in the middle of an argument. It may have been an editorial touch requested by Mrs. Stofer, but probably resulted because the artist wasn’t sure what to do with the shadow cast by Jacob's mustache, and painted it to resemble a yawning cavern.

Color photography has been around far longer than most of us realize, but it didn’t become practical until Kodak got into the game in the 1930’s and even then wasn’t widely adopted by consumers until it became more affordable in the ’60’s. Until then, black and white portraits were sometimes spruced up with applications of transparent dyes. Parents who waved goodbye to a son in uniform during World War II, could expect to receive a handsomely hand-colored portrait ready to be parked on the mantle to await his return.

After the war, out-of-work professional colorists must have flooded the market, ready to add a distinctive flair to amateur snapshots of important events such as Ben and Mary Stofer’s 50th anniversary. Unfortuantely, like those classic movies colorized by a certain cable network back in the early 1980’s, the hues were seldom completely convincing.

And, finally, one of the most surprising finds in the Stofer collection may be one of the family’s earliest snapshots, a completely ordinary photograph taken shortly after the turn of the century, probably on one of the recently-introduced Kodak Brownie box cameras.

I’ve featured a cropped and straightened version of the photo on another page, but wanted to show it without any fussy tidying this time, much as it must have looked when it arrived in the mail from the laboratory. Now you’ll see why I think it was someone's very early effort at mastering a brand new and completely unfamiliar technology, that would soon sweep the country.

Photographs courtesy Dale Ann Johnson and Ashley Gresham