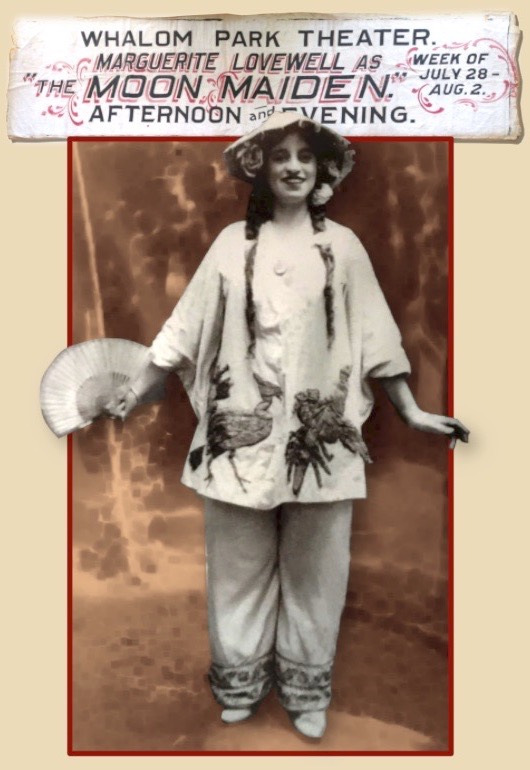

2017 may have been a fairly slow year for historical discoveries concerning the Lovewell family, but it had a firecracker finish, capped by a view of soprano Marguerite Lovewell in her starring role as Meevya in “The Moon Maiden,” an operetta which opened in 1913 in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. Besides the star’s luminous glow, I was most impressed by the costume that was designed, with subtle sleight-of-hand, to pass off the statuesque Miss Lovewell as a diminutive Burmese peasant girl. By a happy bit of luck, the same day the picture showed up in my in-box, I found the original banner announcing the production at the Whalom Park Theater, being auctioned on eBay.

Now if I could only find some hint of what Stoddard’s lyrics and Berton’s tunes sounded like, we’d have a complete exhibit. Alas, the pair were not Gilbert and Sullivan, and their minor operetta hasn’t stood the test of time. The production is noteworthy as the closest Miss Lovewell ever got to the operatic stage of her youthful dreams. After 1913 she would cede the roll of Meevya when the show went on tour, and confine her performances to concert halls and church auditoriums.

When Phil Thornton reminded me a few weeks ago of Thomas Lovewell’s Wyoming adventures, Phil had already found most of the gleanings from Laramie newspapers that I shared last time (“You Know That Wyoming Will Be Your New Home”) as well as a couple of items I hadn’t spotted. One of these is a story reprinted in Courtland papers, which is absolutely priceless, although anyone less familiar with the Poole family might need a quick refresher.

Thomas and Orel Jane Lovewell’s eldest child Josephine, born at White Rock on Christmas Day of 1866, married a former cowboy from Wyoming named Walter Poole and had three children who thrived, Lunetta and two boys, Winnie and Earl. The Pooles were part of the entourage who tagged along with patriarch Thomas Lovewell and his sons Grant, Stephen, and William Frank, on summer outings to develop the family’s mining interests in southeastern Wyoming.

The summers spent there were were sometimes marred by inclement weather. Thomas returned to Jewell County in 1905 complaining that he had been soaked with rain every day while he worked his mines. And that was after his trip to Wyoming had been delayed until June by spring showers and a late snowfall in the mountains. These were mere annoyances, however, compared with the great dynamite fiasco of 1903.

The Wyoming papers that year had been full of tales of grisly accidents caused by the mishandling of explosives. One man lost a finger, his partner an ear, while both men were besides blackened from head to toe. A man near Laramie had his head blown off when he tried to tamp a second stick of dynamite down a hole where an earlier charge had failed to ignite. The hills west of Laramie, it seemed, were thick with amateurs armed with deadly high-explosives. Not only were the foolhardy miners at risk, as readers of a new paper called the Cortland Comet were told, so were innocent wives and children.

Mrs. Walter Poole had been sick for several days with a cold, the result of falling into the creek near the line. Just before the rest of the family had retired, the children noticed the fuse of a box of dynamite capsules was on fire. Winn jerked the door of the cabin open and called to his mother as he ran out. She saw the fire and ran out. Walt was out looking for Earl and Steve Lovewell, who had gone in the morning to Wood’s Landing, twelve miles to get medicine for Mrs. Poole. Walt heard the screams and the explosion followed. He found his wife, completely exhausted, and wrapped her up in what was left of the tent, until they could find bedding. The explosion was heard five miles and nearly everything was destroyed in the fire.

The story of the Poole family’s scary brush with a box of dynamite literally took the prize - or at least the story was credited as a “Prize Item” presumably from some Wyoming paper known as the Monitor. The rather confusing scrap printed in a new paper at Courtland called the Comet on August 28, perhaps distilled from a longer piece that explained things more fully, gave the mistaken impression that the Pooles had been living in a tent which was blown to smithereens. The same day the item appeared on page one of the Comet, Courtland’s more credible newspaper, the Register, gave an account on page four that came directly from Josephine’s husband, and explained some of the oddities, though it added some new ones.

Word comes from Walt Poole that they had an explosion and a narrow escape in the mining cabin out in the mountains. Some way a stick of dynamite caught fire, one of the girls saw it, gave a terrible scream and ran. Walt was away after a doctor for Mrs. Poole and a youngster who were quite sick in the cabin. When Mrs. Poole heard the scream she grabbed the boy and ran out of the cabin and had just got outside when the dynamite exploded, wrecking the cabin but no one was hurt. It was certainly a narrow escape for Mrs. Poole and the boy.

While neither version would win any journalistic prize for clarity, merging the two of them results in a general fog. Josephine was certainly under the weather, but who is the unnamed “youngster” who also needed medical attention? For that matter, who was the first child to become aware of the danger, and who was the first to run outside? According to the story first printed in Wyoming, “the children” saw that the fuse was lit, while Josephine’s son “Winn" called out to his mother as he ran out the door. In the story told by Walt, “one of the girls” noticed that the dynamite was on fire and screamed as she ran away. Josephine then “grabbed the boy” and dashed outside just as an explosion rocked the cabin.

Although Josephine and Walt had four children, their second daughter Pearl died the same day she was born in 1899. In other words, they had only one daughter, Lunetta, who would have been 16 the day the dynamite caught fire. The only other child in the cabin would have been Winnie or “Winn,” who was 12. Lunetta and Winnie’s brother, 7-year-0ld Earl, was apparently with his Uncle Stephen, who had gone in search of a doctor early that day. Although by his own report, Walt Poole was fetching a doctor, it seems likely that he had given up trying to learn what had become of Earl and Stephen and was heading back to his cabin when he heard shouts followed by an explosion.

Perhaps everyone was too rattled by the blast to put together a coherent story for the press. Phil did notice that as soon as Walt got back home from the gold fields he went to Courtland and bought a nice new carriage. Perhaps all the dynamiting turned up a few nuggets after all.