When George A. Forsyth finally returned to the scene of a military engagement he had described in “Thrilling Days in Army Life,” it took him a while to get his bearings.

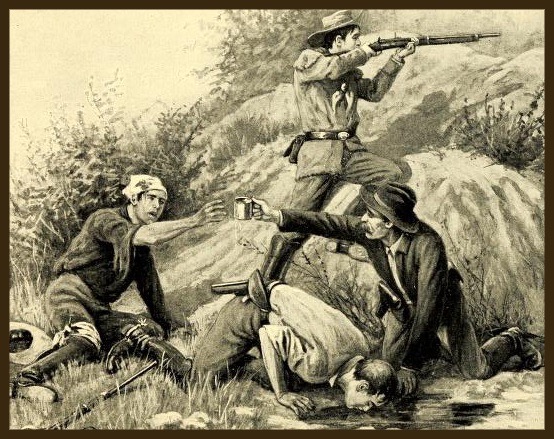

Beecher Island did not look the way he remembered. It wasn’t just that forty years of erosion had nibbled away here and there at the margins of the Arickaree fork of the Republican River. The wooded sandbar where Forsyth and his band of scouts made their stand against waves of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors in September of 1868, seemed to be situated the wrong way around. As he began to square the geography of the place with his memory of it, he realized that the attack had not come from the east, as he had confidently written ten years earlier, but from the northwest.

His book may contain other lapses of memory. Seeing a tall chief with a distinctive headdress riding up and down the Indian line at the start of the battle, Forsyth remembered saying to his guide, Sharp Grover, “Is not the large warrior Roman Nose?” The problem with Forsyth’s identification of Roman Nose so early in the fight, is that he hadn’t arrived on the scene yet.

Modern writers tackling the subject of Beecher Island suggest that the embattled scouts had only a sketchy idea of where they were (Most thought they were on Delaware Creek) or which tribes they were facing, let alone the name of the war chief who seemed bent on engineering their doom. It's likely that Forsyth learned about Roman Nose later on, incorporating the famous chief into his memories of that first day.

Forsyth and everyone under his command would have been killed if they had not managed to take refuge on Beecher Island, and had not been equipped with those deadly Spencer rifles and over a thousand rounds of ammunition. Only five of Forsyth’s men died from the nine-day ordeal, and a number of the survivors wrote about their experience. Many more seem to have reminisced about it, including some who were never there.

At least, good old Republic County pioneer Harry Wallin did not claim to have witnessed the battle first-hand, to have squeezed the trigger of his Spencer from the cover of a hastily-dug rifle pit, surviving on stagnant water and decaying horse flesh until rescuers arrived. Wallin’s chief mistake was to believe that he had seen Forsyth’s Scouts galloping off toward western Kansas, after actually watching the Kansas Adjustant General's dusty entourage troop through Scandia on a fact-finding mission in June of 1869. However, Wallin’s garbled account of Beecher Island for an 1898 issue of the Belleville Telescope was not the most notorious history of the battle to be printed in a regional paper.

Sigmund Schlesinger, a veteran of Forsyth’s company, penned a letter to the editor of the Kansas City Star in 1927 to take issue with what he found to be erroneous details in a story written by a man who claimed that, at the age of 17, he had been the youngest of the famed scouts pinned down on a sandbar in the Arickaree fork. Schlesinger knew better because, at 19, he had been the youngest man in the unit, and he was able to blow a number of holes in the story printed in the Star. F. M. Lockard wrote a piece for the Chronicles of Oklahoma that same year, citing other old-timers who had been caught trying to steal a glimmer of reflected glory from Beecher Island. The charlatans were sometimes tripped up because they had filched bits from Forsyth’s book, fragments of history which Forsyth had misremembered.

I brought up the matter a few days ago after NBC newsman Brian Williams, whom I knew briefly three decades back, seemed to have been caught stealing some reflected glory for himself with a story about a helicopter he was in taking enemy fire, when it didn’t. I suggested that the real culprit might be memory itself, which is not the flawless recording device we wish it were. It can conflate, confuse, and confound, despite our best efforts to give a full and accurate report of what really happened. Now, the feeding frenzy is well underway and every story Brian has ever told is being called into question. Did he really rescue a puppy from a burning house? Was he truly robbed at gunpoint as a teenage Christmas-tree salesman? Did he actually shake hands with Pope John Paul II? Photoshop came into play immediately, with practicioners gleefully producing images of Brian alongside Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, George Washington, and reporting live from the moon.

Dave Lovewell, who knows the difference between taking enemy fire and not taking enemy fire, was having none of my excuses. He also rendered the most level-headed and non-judgmental verdict on Brian Williams I’ve seen yet. “The sad thing here is that the true story he had to tell of that day did not need any embellishment... I am inclined to think he needs counseling rather than scorn.” Unfortunately, there is no market for a network news anchor who needs truthfulness counseling. Worse yet, the 1927 item in the Kansas City Star in which an imposter claimed to be a veteran of the Battle of Beecher Island, was written by a man named Williams. I’d check Ancestry for a familial relationship, but I’m afraid to.

On a bright note, in a blog entry last month I likened Dave Lovewell's killer smile to that of 1950’s and ’60’s Western TV character-actor Jan Merlin. A ding on my email client a few moments ago alerted me to an incoming message from Jan, thanking me for the mention and the recollection. I was thrilled to hear from him, but I also wish now that I had written something about his 1975 Emmy for writing “Another World” and his service as a torpedoman during World War II.

I do hope he’s not tired of so may of us remembering him as a really great bad-guy. He’s also had a long and varied career that needs no embellishment.