When I was seven years old I knew Lovewell, Kansas, only as a sparsely-populated patch of earth we drove through on the way to Superior on Saturday afternoons. My mother and two of her sisters seldom failed to make that weekly pilgrimage north of the Republican River to a small city in southern Nebraska. Superior was home to about 3,000 people, three grocery stores, one meat market, and zero sales tax. There was also a movie theater where a precious quarter allowed me to feast my eyes on trailers for coming attractions, a color cartoon, an installment of a black-and-white serial of reasonably recent vintage, and a current feature-length film.

Even in the 1950’s Lovewell could not be mistaken for a bustling village. The only signs of prosperity visible from the dusty road, aside from a few well-maintained cottages, consisted of a grain elevator, a rail depot, and a fine new school building. At least it was three decades newer than the school I attended in Formoso.

While helping my mother publish her booklet of Formoso history in the 1980’s, I was surprised to learn that my old hometown had once been a lively trade center of about 450 residents in the first decade of the 20th century. Lovewell was apparently every bit Formoso’s equal, if we are to put any stock in the hyperbole of George W. Dart’s description of the village as “the metropolis of Sinclair township," in an item published in the Jewell County Monitor in 1901.

Among Lovewell’s assets Dart listed “two grain elevators, two merchandise stores, two churches, one drug store, one harness shop, and one lumber yard.”

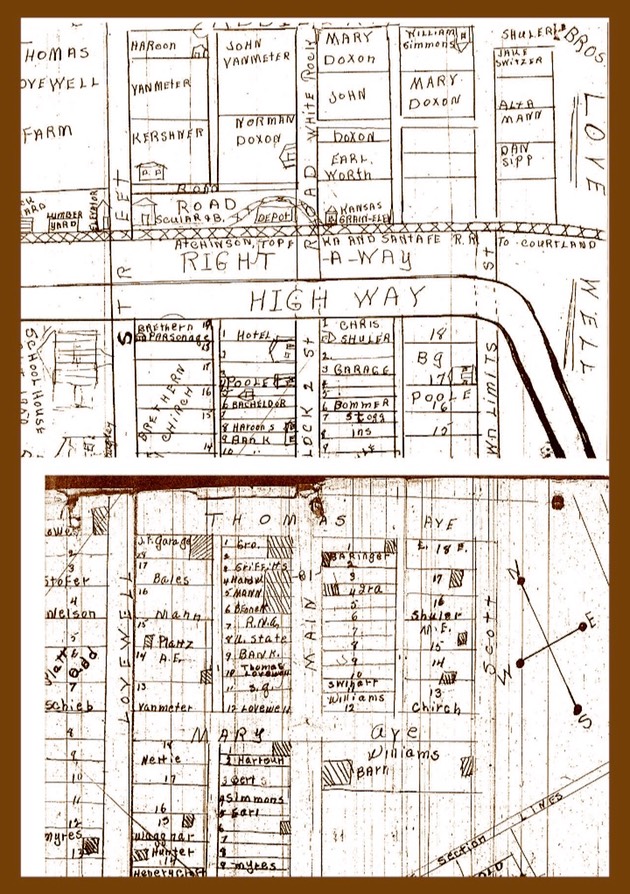

For an indication of what else the village had to offer a decade or two later, as well as exactly where various families resided and farmed, we have a hand-drawn sketch of the layout of the town from Orel Elizabeth Poole's unpublished Sketches of the White Rock.

Orel was a granddaughter of Thomas and Orel Jane Lovewell, and grandmother of a frequent contributor to this website, Phil Thornton. Having leafed through several pages of Orel Poole’s typewritten manuscript, I rather doubt that the young writer was responsible for the consistently eccentric spellings on the map, e.g., “Chirch," “Brethern," "Right-A-Way.” However, I also like to believe I’m not responsible for my own typos, so take my opinion for what it’s worth.

I’ve sometimes referred to Formoso and Lovewell as twin Kansas towns, born a few miles and a few months apart. Both had been created to coincide with the arrival of a railroad. Each had grown by poaching the population and business interests of another nearby town. Lovewell was an attractive alternative to the stagnating pioneer settlement of White Rock, while many of the citizens of Omio were offered inducements to drag their homes and commercial ventures three miles north to the burgeoning young town of Formoso.

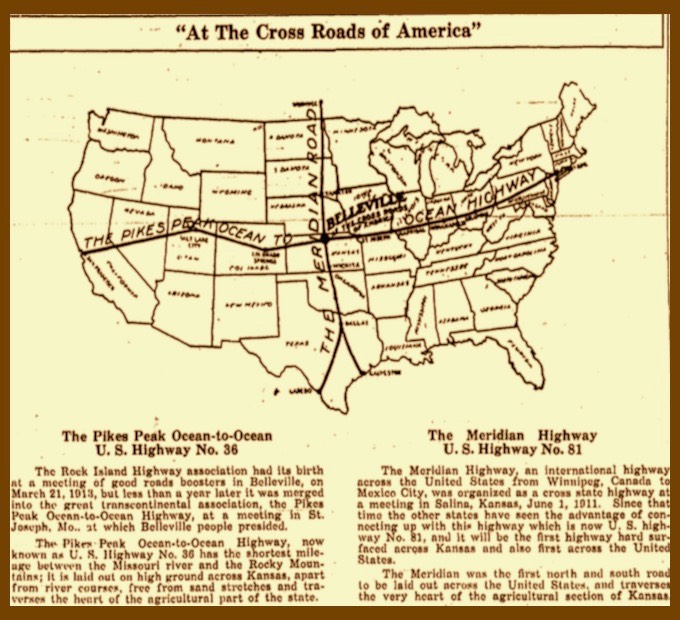

As we can see by the postcard memento of an I.O.O.F. anniversary event, the village of Lovewell could still draw a crowd in 1916. However, road work already taking place six miles to the north must have been an ominous sign for the businessmen of Lovewell. The arrival of the Pikes Peak Ocean-to-Ocean Highway, an east-west corridor, was about to cross paths with the Meridian Road at Belleville, allowing the county seat of Republic County to claim the title of “Crossroads of America.” The arrival of the automobile would prove to be bad news for small towns in general, but being located more than five miles away from the nearest hard-surface road would amount to a death knell that tolled in slow motion.

Of course, by then the village had served its primary purpose, as far as my generation is concerned. Take me for example. Three of my great-great-grandparents are represented on the map from Orel Poole’s book. They lived in Lovewell for a time, as did all eight of my great-grandparents. My grandparents on both sides met and fell in love there. My father was born there. So were three of my mother’s older siblings. Lovewell was a sort of ground zero for my family, a fact that never hit home until recently.

Although Federal Highway 36 West to Kansas 14 South is the quickest way to get from Formoso to Superior, we usually took the Webber Road. While this was a more direct route, it took longer because it was unpaved most of the way and packed a pair of vicious hairpin curves just ahead of the moldering village of Lovewell. Still ahead was a nerve-tickling drive across a creaking one-lane bridge over the Republican River.

My aunt Irene, who always did the driving, probably chose the route because it gave the sisters in the car a chance to reminisce. They could gaze at the acreage Irene had once farmed with her late husband, and the farmhouse her sisters helped to tidy up ahead of monthly club meetings. They might have tried to spot the location of the smithy where their father learned his trade, or see if anything remained of the one-room school where Formoso teacher Florence Westin had taught not so many years before, when it was reputed to be one of the last such schools in Kansas.

Taking that Webber road to Superior must have seemed a kind of time-travel for my mother and my aunts. And at the end of the trail lay a movie for me and an afternoon of tax-free shopping for them. Sweet.